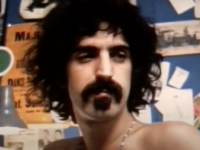

My first memories of Frank Zappa’s Sheik Yerbouti are a vague recollection of disappointment. I’d initially only ever “owned” around half of the album, on cassette tape. The crudely chopped half was a snobbish deletion. I had already entered the “discerning fan” season, and was discovering the splendor of instrumental composition – specifically the starts and double-takes, the sheer eyebrow glee of Zappa’s omni-blasphemous compositions. “Lyrics exist for those who need them” was my prized cue.

Structured almost like an in-concert mix-tape, Sheik Yerbouti combines Zappa’s grinning scatologies and sociopathic irreverence in blindly upbeat rockin’ rhythms, drops in some crudely gifted extended solos and adds those delightfully arb spoken-word mash-ups that first sneaked into view with the Lumpy Gravy projects. Mirroring live Zappa gigs from the 1975-80 period, Sheik Yerbouti showcases crowd sing-along numbers like “Jewish Princess,” “Baby Snakes,” the slapstick magnificence of “Dancing Fool,” “Bobby Brown Goes Down” and the teenage rock melodrama of “Tryin to Grow a Chin.”

The result is actually one of the classics from Zappa’s “rock” canon, along with the arguably superior Overnight Sensation, Joe’s Garage and Apostrophe.

‘Fountain of love’

Perhaps the definitive anti-love figure of 20th century popular music, Frank Zappa had no time for the frills and, to him, delusions of romance. He drops the slang pretense of being “into” someone, preferring the geographic accuracy of “I, have been in you, baby” and the mechanistic prediction that, indeed, “when we get through, I’m going in you again.”

Appropriate to his devious sense of fun, the opening “I Have Been in You” is cloaked in the sheen of your typical romantic ballad – all sparkly, floating synths and crooner rhythm. The initially smarmy texture of Zappa’s vocals becomes increasingly lurid and greasy, as the debauchery of sentiment grows. Elsewhere, via one of his multiple characters, he sings praise to a girlfriend exceptionally talented in the world of Eros, in a flip side to Hall and Oates’ unintentionally hilarious “Maneater.”

With “Jones Crusher” (“better get the gauze …”), Zappa further elaborates on the pitfalls of romance and its melancholy sparkle. Live performances of the self-explanatory “Broken Hearts are for Assholes” typically included fingers pointed and, indeed, middle-fingers aimed at the audience, and finally at himself and the band, during the chorus: “And you’re an asshole too, so whatcha gonna do? ‘Cause you’re an asshole,” neatly cementing the generosity of his insults.

Although Frank Zappa’s more infantile scatologies (not quite the tautology, it seems) are novelty items, constructed as they are on the punch-line of shock, there is a general, insightful satire that unites all of his humorous output. Zappa strategized against what he felt to be a pandemic of hypocrisy in the modern human condition and, well, the general phenomena of what he calls stupidity: “Some scientists claim that hydrogen, because it is so plentiful, is the basic building block of the universe. I dispute that. I say there is more stupidity than hydrogen, and that is the basic building block of the universe.”

Consequently, in his frame, Zappa never wanted for subject matter. He was surrounded by a seemingly inexhaustible mine of human quirks. The sheer ridiculousness of human patterns – their, ahem, “culture” – would inform the near-encyclopedic sweep of Zappa’s humor.

A central – and to this fan, infuriating – credo of Frank Zappa was his deliberate quashing of perceived distinctions in quality as a question of style. Zappa insisted that musically plain, intellectually unsmiling pieces of gratuities like the notorious Flo & Eddie period, lyrically restricted to crude infantilism, was indistinct from the shocks of gorgeousity characteristic of his more adventurous instrumental inventions. Both structures entertained him. The notion of “art” was an affectation for the man who would often blend doo wop, gag-reflex, Varese-ian nods, a private language of sound, and hitherto-unknown twists in rhythm’s relation to melody. Often in the space of a song.

‘I knew you’d be surprised’

The mini-epic “Flakes” is an outing into another of Zappa’s favorite terrains: laziness, absence of vigor, boredom as spiritual condition. (The earlier “Yo Cats” focused on ever-procrastinating studio musicians, while One Size Fits All featured “Po-jama People,” where dimness in general was un-celebrated.) “Flakes” takes on the middle-America of service delivery, even letting (a caricatured) Bob Dylan drawl a complaint about his washing machine’s dubious fixedness.

For a guy who tended to work 12-hour days, and churned out around 70 albums of wildly divergent, often unprecedentedly original music in the space of a quarter century, the rest of America was not exactly industrious.

An anti-ode to talented multiplying ineptitude, “Flakes” raises to a slow-building climax, with a bridge attaining a nicely tongue-in-cheek Armageddon. The eponymous Flakes, zombies from Lunch-break-Land, ultimately rise in numbers to take over the world while it sleeps: “We’re coming to getcha, we’re coming to getcha, we’re coming to getcha, we’re coming to getcha.” It was very possibly a recurring nightmare for the composer.

Elsewhere in Sheik Yerbouti, Zappa’s instrumental inquisitions take momentary center-stage via the crackling distortion of guitar on the precarious blues-run “Rat Tomago,” followed by the short, gleaming Patrick O’Hearn “Rubber Shirt” bass solo, and the bristling texture of Zappa’s take on the electric guitar tango on the title track. Both “Rat Tomago” and “Sheik Yerbouti” are booby-trapped with tasty surprises in the time-continuum, showcasing many atonal sidesteps, many a pothole and wormhole redirecting the flow of sound. Grinning stuff!

Sheik Yerbouti carries on into concert favorites “City of Tiny Lites” and “Baby Snakes,” before plowing into “Wild Love” and the epic “Yo Mama,” instructing its audience to get out into the world and do things their own way – followed by a sonic example of just that, via Frank Zappa’s extensive, fantastically layered guitar solo.

[First published by Kagablog]

- How the Pixies Changed Everything With ‘Surfer Rosa’ - July 12, 2023

- Frank Zappa – ‘Funky Nothingness’ (2023) - June 30, 2023

- How Jim White’s ‘Wrong-Eyed Jesus!’ Changed My Mind About Country Music - June 14, 2023