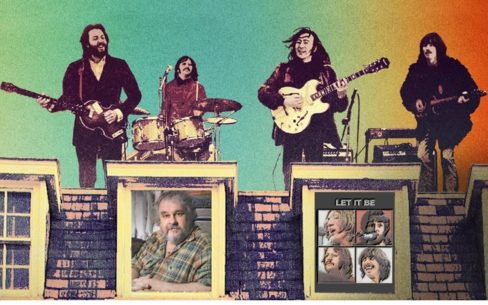

Just when you think the Beatles couldn’t top themselves after the deluxe, reimagined collections from the last few years that culminated with Abbey Road, Peter Jackson’s epic Get Back from 2021 has given us a detailed, artistic, and historical three-part film that can rightly be deemed a triumph, and not just for the band.

When the project was starting to be publicized in 2019, Jackson made it known that what he uncovered wasn’t the gloom and doom that seemed to permeate the 1970 film, and he was right. But tone aside, there is so much here that addresses various aspects of the Beatles and informs certain facets of their history as a group.

Acclaimed director Martin Scorsese stated a fundamental truth in an essay that accompanied the 2007 remastered DVD release of the Beatles’ second film Help! “For those of us who were alive when they were on the airwaves, just the mention of their name brings back an entire world – not just ‘the ’60s,’ but something else, something mysterious, exhilarating. The more you listened to the music (and we all listened to it a lot), the more your connection to it strengthened. … We expected it. But we didn’t really stop to think of the wonder of it” (italics mine).

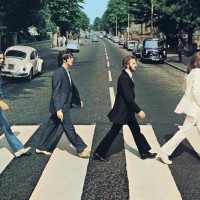

Scorsese spoke volumes for those of us who followed the Beatles closely throughout the contentious 1960s, where it seemed as if the heights they achieved would never end. That is, until it all came crashing down not long after the accomplishment of 1969’s Abbey Road, their final album recorded as a band. In the 1970 film Let it Be, it was almost as if the Beatles were unrecognizable to those of us who had been experiencing their output as it occurred.

Though recorded and filmed prior to Abbey Road, the releases of Let it Be as both an album and movie happened after the Beatles’ very public and acrimonious breakup, and the film’s storyline seemed to emphasize what appeared to be the unpleasantness of the end of the biggest band on earth. This is even apparent in Martin Scorsese’s aforementioned notes: “… It turned out that there were all the usual problems – you could see them in Let It Be.”

That might include the quality of what we saw on the theater screen, as the level of quality wasn’t what one came to expect from the Beatles: filmed in 16mm, the movie had a graininess that was distracting, and that only heightened the unpleasantness of the entire enterprise – and the music combined with the conversation would sometimes seem to be indecipherable.

The preface for Jackson’s Get Back may have served as a primer for anyone not familiar with the Beatles’ history, but it gives an indication as to why they embarked on this project. In Part 2, there is a conversation between John Lennon and Paul McCartney that was secretly recorded without their knowledge, where Paul mentions that within the Beatles John was the “first boss” with Paul the “second boss,” and that is revealing when you consider how their long and winding road led to their considering this project.

In the beginning, the Quarrymen was John Lennon’s band. Rather than see the young and talented Paul McCartney as a rival, Lennon convinced him to become a member. Paul knew George Harrison, and when George demonstrated his own prowess on the guitar, John agreed that George could join. Later they recruited drummer Richard Starkey — whose stage name was Ringo Starr — to replace Pete Best. It was this history that led to their always being referred to as John, Paul, George and Ringo, in that order.

John’s role as leader — or as Paul put it, “first boss” — was never literal, but the other members recognized that Lennon was the one who was responsible for the band’s formation. When they performed on stage, John had his own microphone, with Paul and George sharing one for backup. When they started producing singles, it was John’s songs that were the A-side and mainly the hits — their first single “Love Me Do” with Paul on lead vocal wasn’t received as well as they’d hoped, but the follow-up with “Please, Please Me” with John singing lead was their first big hit in the U.K. What followed in this early period (“From Me to You” and “She Loves You”) were sung by both John and Paul in unison and/or harmony, with George joining in at various junctures.

It’s almost appropriate that the song that broke the Beatles into the U.S. charts — and their gateway to the rest of the world — didn’t feature one Beatle leading the way, as John and Paul both sang throughout on “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” However, on the singles that immediately followed it was mainly John who would take the leading role as vocalist and songwriter (despite the fact that any tune written by Lennon and/or McCartney would be credited to both). But that started to change, beginning with Paul’s “We Can Work it Out.” The Beatles were such a phenomenon that their singles started to be labeled as double A-sides: For the most part it was Paul’s song that would be listed first, and the preferred ones played by radio stations.

After the death of their manager Brian Epstein, McCartney — perhaps recognizing that with Epstein’s passing the Beatles might begin to drift apart — began taking a larger role in the creation of the Beatles’ endeavors. The concepts for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Magical Mystery Tour were largely Paul’s.

The double album The Beatles (aka “The White Album”) was a slight detour, becoming a clearing house for an astounding number of songs they had created while in India visiting the Maharishi, but Paul again provided the concept for the following project. The idea was to demonstrate that the Beatles as he once put it were at heart still a “cool little dance combo,” and to demonstrate they could still perform live as a four-piece without additional production – ostensibly in front of an audience, as they had back in the day.

But their music had evolved to where they realized that in order to bring their songs to life they needed an additional musician on keyboards, and this is how old friend Billy Preston was recruited to contribute his talents to the project.

It appears that Lennon was fine with going along with Paul McCartney’s ideas for those aforementioned albums, and with being a Beatle. One can speculate this would have continued indefinitely had John Lennon not met Yoko Ono. It might not have been an obvious epiphany, but John saw how he and Yoko could be a creative force unto themselves — something that otherwise might not have been apparent with Paul taking the role as “first boss.” But their meeting in itself was not yet enough for John to consider leaving the Beatles altogether.

Get Back puts to rest the long festering rumor that it was Yoko who broke up the Beatles. Here she is only making her presence known when she jammed with the band, but overall was content in John being totally invested in creating and playing music with his old friends from Liverpool: Ono is seen quietly sitting at Lennon’s side reading, or chatting with Linda Eastman.

From one candid conversation heard between the other Beatles in the couple’s absence they acknowledge and accept that the two were madly in love, and Paul even jokes that it wouldn’t make sense if in 50 years’ time the press blames the band’s breakup on Yoko for “sitting on an amp.”

With that resolved, there are other conversations that reveal what would be the actual reason for the Beatles finally calling it quits. It was one that had to nothing to do with Yoko and everything to do with the Beatles as a business. John had met Allen Klein, who was managing the Rolling Stones, and was impressed with Klein’s knowledge of the Beatles’ business situation and his ideas of how to address it.

After Abbey Road, Paul ultimately decided that he did not care for what Klein had to offer, and preferred Linda’s father Lee Eastman handle their affairs. This led to Paul’s efforts to end the Beatles as a business venture, to where he would pull out altogether. (A great source of the story behind the dissolution of the Beatles’ business during this period is The Longest Cocktail Party: An Insider Account of The Beatles & the Wild Rise and Fall of Their Multi-Million Dollar Apple Empire by Richard DiLello, which includes reprints of articles from the London Times outlining what happened with Allen Klein.)

Following what they saw as interminable hours of recording and filming for what was then known as Get Back — and not eager to yet tackle its mountain of work – legend has it that it was again Paul who suggested to longtime producer George Martin that they record their next album “like they used to.” In other words, having gotten the live recording idea out of their system, the next album which came to be titled Abbey Road would welcome appropriate production and orchestration.

After that album was completed, there was no indication that they as a band were over: The Beatles Forever by Nicholas Schaffner documents a discussion between the members as to how the number of tracks for each songwriter would change for any future albums (increasing for George Harrison and Ringo Starr). This is reinforced in the film, when George discusses how he has amassed a good number of songs that he might record on his own, in addition to contributing to future Beatles albums.

Fast forward to what turned out to be a fateful meeting between Peter Jackson and Apple Corps management. As quoted on the Disney Fan Club site D23, Jackson explains what happened: “I went to London to get some footage from the Imperial War Museum, for my [2018] World War I documentary They Shall Not Grow Old, and [while I was there] had a meeting with Apple Corps … and all they wanted to talk to me about was virtual reality and augmented reality. They must’ve read an interview with me where I said that I was interested in that. So they wanted to pick my brain, because they were planning on a Beatles exhibition; it was [potentially] going to have some sort of VR and AR.”

But Jackson was a voracious Beatles fan who had other ideas in mind. He inquired about outtakes for Let it Be and upon learning that Apple was considering a long overdue followup, Jackson volunteered to take on the task on one condition: that he would be able to review what was available before committing to the lengthy amount of time that he would have to invest in assembling a new film. If, based on his knowledge of the original cut, what he was about to wade through was going to be a miserable experience he wanted the opportunity to say “thanks, but no thanks.”

When Jackson examined the 60 hours of footage he had discovered that his expectations for bad vibes to permeate throughout rarely happened, and enthusiastically committed to completing the new film. Jackson also obtained 160 hours of audio from the sessions, and using AI technology was able to parse out the different sounds to where what originally appeared to be unmanageable noise could be heard distinctly and more clearly.

Compared to the grainy print of the 1970 movie, Jackson would deliver startlingly improved images, using the same techniques he applied to the century-old footage for They Shall Not Grow Old. (Another revelation from Get Back was a conversation that disclosed the reason for the theatrical film’s graininess: it was shot in 16mm because it was originally conceived as a television event, but instead would be blown up to 35mm for theatrical distribution.)

Retaining the original title of Get Back, a 2.5 hour film was scheduled to be released to theaters in September 2020 — or at least that was the plan until COVID-19 made it necessary to delay the release. While not much was positive about that pandemic, what it did was make Jackson and Apple rethink the standalone movie idea.

This resulted in reworking the film into what became a whopping ~7.5 hours of an inside look into the Beatles’ creative process, to be streamed by Disney+ with the first of three parts premiering in 2021 on Thanksgiving Day in the U.S. A theatrical release of the rooftop performance and a DVD/Blu-ray release of the entire video would be scheduled to follow in 2022.

The most remarkable aspect of the refurbished Get Back is witnessing how the Beatles were concentrating on being the Beatles, as in their minds they still were the Beatles, and enthusiastically so: They were not just begrudgingly going through the motions to get through it, as the original film might have indicated.

Some viewers may find themselves lost and even a bit bored by what might appear to be endless footage of their working out material, but others will be fascinated by the band’s process in creating the songs they were planning on performing — making fans even hungry for even more.

We see the band members all make suggestions for whatever song was being conceived and in progress. We witness them jamming on oldies, other artists’ tunes, and — in an effort to come up with original material in the short window they gave themselves – even revisiting tunes they previously recorded (“Across the Universe” chief among them). We see the early, formative versions of songs that would later appear on Abbey Road and on the members’ solo albums.

Throughout there is little ambiguity as to what we’re seeing and hearing, as Jackson smartly includes captions alerting the viewer to significant items and events that might not be obvious in the conversations. The title for every song they’re playing (along with naming each song’s authors) is identified. So are all the key participants in the film, from companions to invited guests to the various crews. There’s also a day-by-day timeline ticking down to a pivotal concert date that seemed doomed by the lack of consensus as to where to have it and the scope of it, let alone having to figure out the actual logistics.

Despite the immense challenge of having new songs for a live performance, in the end the Beatles pulled off the original challenge of performing live with the now-iconic rooftop concert that comes close to the video’s finish. Speaking of which, if it’s even possible to have made Get Back even better, it would have been for Jackson to end this event with some of the other finished tunes not performed on the rooftop (including “Let it Be” and “The Long and Winding Road”), only providing “Two of Us” with Lennon performing while sitting on the floor.

In light of what we get, that is a minor omission. Get Back is an artistic achievement unto itself that separates itself from the original 1970 Let it Be as being a totally different animal. Jackson was at the right place at the right time. Given the vast improvements for what we see and hear, he was the perfect person to do this.

In rescuing Get Back, Peter Jackson did something miraculous for those of us who followed the Beatles during their heyday: he brought back the wonder of it.

© 2022 Mike Tiano. All rights reserved.

- Remembering Billy James: ‘He Was One of the Good Ones’ - May 15, 2025

- ‘Becoming Led Zeppelin’ (2025): Movie Review - March 11, 2025

- Grateful Dead’s Kennedy Center Honors: What Was Missed - January 27, 2025