Stripped bare for a new version of the Beatles’ penultimate record, “Across the Universe” finally found John Lennon alone in his ringing chorus: “Nothing’s gonna change my world.” But Let It Be … Naked, released on Nov. 17, 2003, instead explored a world that had been drastically changed.

For years, raw, unedited tapes from 1969 sessions recorded before producer Phil Spector was called in to rescue the Let It Be project served as a coveted treasure for any Beatles fan. Sadly, Spector’s reclamation work had included smothering some of the group’s most honest songs. They were earthy and emotional, flawed but yet (despite itself, at times) kinda fun. That is, until he added a gauzy cloak of strings and chorus-choir schlock.

It was an unfortunate end to a noble concept: Getting back to playing as a band.

That may have been all that was left for guys still smarting from the thudding failure of 1967’s Magical Mystery Tour – this trippy movie put out months after such a thing was hip. In the same way they had grown distracted by easy pop success in the mid-1960s, the Beatles would then discard psychedelia. Still, there was a curiosity in hearing the Beatles reach with some uncertainty for something beyond their grasp.

The band was, by then, usually comprised of one, two or three members. The first results, perhaps idealistically, were issued in 1968 as a creative temper tantrum called The Beatles. They were powerful enough to put out anything they wanted, but the rich tapestry of the Beatles’ previous work couldn’t be recreated in pieces.

They reconvened early the next year again as a foursome. Forced to deal with a very grown-up situation for the first time in years – no faking it with effects, alone in a room making music – the Beatles at first found that they simply couldn’t. The album was eventually shelved. Still, the blessing is that Let It Be, whatever the anguish it caused the Beatles themselves, was tirelessly, relentlessly documented.

The recording of this album was filmed to finish a picture deal they’d signed in the heady days of Hard Day’s Night. And so, first only in baby steps, we came to appreciate how hard it was for these talented people – so public, yet so clearly sheltered – to make honest music again.

After the tapes sat dormant for some time, John Lennon handed the whole mess to Phil Spector – who’d had one of his by-then-rare moments of lucidity in producing John’s stark and echoing “Instant Karma!” single. The results, once called Get Back, were retitled Let It Be when the album wasn’t released until the Beatles were disintegrating in 1970.

This would be no triumphant reunion. Instead, Let It Be become another example of how a great group can sometimes be better understood by exploring failures, rather than listening once more to obvious successes. It always seemed so ripe for re-evaluation. We got our first official glimpses of what might have been with Let It Be … Naked.

This project, which peeled away Spector’s excesses, has since been superseded by the heralded Get Back documentary and a broadly expanded reissue of the official LP. Some of these initial reworkings (but not all) were rendered moot – but in their moment, this was revelatory stuff. It’s easy to see how fresh insights gained here cleared the way for the larger reclamation project that followed. Peter Jackson never rewrites their ending without the permission given by this album.

Of course, no amount of burnishing will transform Let It Be into the Beatles’ best record. Spector’s impulse to Vegas up Paul McCartney’s “The Long and Winding Road” is understandable on some level, since even now its remains a wispy weeper.

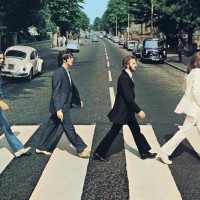

Still, the stark grief of “Don’t Let Me Down” (so Plastic Ono Band), the soaring piety of “I Me Mine” (so All Things Must Pass) and the simple guile of “Two of Us” (ditto McCartney) sound more like where the Beatles were headed than the briefly chummy Abbey Road ever could. Let It Be instead completed the White Album’s artistic bridge toward their later individual personas.

This, rather than Abbey Road, tracks directly toward the hard-eyed brilliance found on Lennon’s first solo album, the hopeful bliss of George Harrison’s future musings and the bedroom-pop perfection of Paul McCartney’s 1970s projects. Minus Spector’s added-on artifice, Let It Be finally feels more like what it always was: A transitional album, but one that opened the door for all of the Beatles’ solo ’70s successes.

- The Bright Spots in George Harrison’s Troubled ‘Dark Horse’ Era - December 29, 2024

- The Pink Floyd Deep Cut That Perfectly Encapsulates ‘The Wall’ - November 29, 2024

- Why Pink Floyd’s ‘The Endless River’ Provided a Perfect Ending - November 11, 2024

Magical Mystery Tour was a #1 album in the US. Hardly the “thudding failure” that DERISO describes

I think DERISO meant the tv movie, not the album.