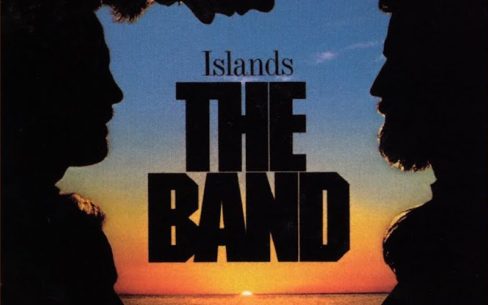

Comprised of a smattering of new music and selected singles and outtakes, Islands was never intended to be a canonical album by the Band. They were simply trying to finish off a contract for Capitol Records, so that the long-gestating Last Waltz package could be released on Warner Bros.

Back then, in fact, the story was that the Band was simply retiring from the road, not from music making.

In that way, Islands should have arrived on March 15, 1977, to more favorable comparisons with house-cleaning compilations of the era like Traffic’s Last Exit or the Who’s Odds and Sods. But the Band had set a standard of long-playing excellence, and they were also coming off a turnaround studio effort in Northern Lights-Southern Cross that seemed to point in a new creative direction.

Plainly, it didn’t – leaving the aptly named Islands to stand as a crooked and unkempt tombstone for the Band’s original incarnation. As such, the project has taken its share of critical drubbings over the years, from disappointed critics and fans alike. But, it’s not without its smaller, more dilated charms:

“LIVIN’ IN A DREAM”

The lightly grooved set-closing “Livin’ in the Dream” is certainly one of them. A calliope-paced aside, this track plays to Levon Helm’s many strengths, from its impish cadence to its scamp’s checklist of big dreams and even bigger flirts.

In that way, “Livin’ in a Dream” reaffirms much of what made the Band so reliably involving, even if it never quite succeeds in making you forget those earlier triumphs. There’s Rick Danko’s keening background vocals, Garth Hudson’s carnival of musical delights (including the trusty Lowrey, but also a hootenanny accordion then a boldly redemptive alto) and Robbie Robertson’s sly curlicue riffs.

Taken apart from history, these couldn’t sound less like components for the desperately sad finale that Islands came to be. But, it is, of course – and that can’t help but color how we hear things.

A sense of dark-hued, end-of-summer finality envelops everything about Islands in general – and “Livin’ in a Dream” in particular, until the very title itself feels bitterly ironic. Then there’s the happy-go-lucky whistle that closes out this song. Knowing what we know now, it may be one of the most desperately lonesome sounds the Band ever put to tape.

Solo albums would, of course, follow for both Rick Danko and then Helm later in 1977. But something is lost forever, as the last song on the last studio album by the five-man edition of the Band comes to a close.

If, in fact, we’d been living in a dream, that dream was over.

“AIN’T THAT A LOT OF LOVE”

One of two cover songs collected on this 1970s-closing odds-and-ends package, “Ain’t That a Lot of Love” felt like a one-off from a group ready to be anywhere else. And, in some ways, it was. But, as the song builds, we learn something all over again about this increasingly distracted quartet.

Robbie Robertson was, at this point, fully focused on The Last Waltz concert and film, while Rick Danko already had his solo debut in the pipeline. Helm, meanwhile, was talking about putting together a guest-packed amalgam that would become the RCO All-Stars – and building his dream studio inside a Catskills barn.

The Band’s most recent tour had been a hit-and-miss affair, perhaps most memorable for a scary off-stage moment when Richard Manuel seriously injured himself in a boating accident. Even Capitol Records, the Band’s long-time label, seemed to have wandered off. Plans to release “Christmas Must Be Tonight,” a lovely Danko-sung holiday paean dedicated to Robertson’s son Sebastian, had somehow never been finalized.

It’s easy to see why the Band would return to something from the likes of Homer Banks, a staff writer at Stax Records who originally released “Ain’t That a Lot of Love” on New Orleans-based Minit Records. Time and time again, chicken-fried R&B leftovers like this one had provided sustenance for the Band, even in the worst of times – as during the long creative drought between 1971’s Cahoots and 1975’s Northern Lights-Southern Cross.

Still, though it’s meant to be in the same vein, “Ain’t That a Lot of Love” doesn’t rekindle the offbeat fire of “Don’t Do It,” and isn’t as imaginatively reworked as “Mystery Train” had been. More particularly, it wasn’t as unexpected as the Chuck Wallis’ b-side “(I Don’t Want to Hang Up) My Rock and Roll Shoes.”

Spencer Davis had memorabily lifted this song’s basic riff for the massive hit “Gimme Some Lovin.'” Taj Mahal also performed a torrential take on it for the Rolling Stones’ Rock ‘n Roll Circus in 1968, having included “Ain’t That a Lot of Love” on his then-current studio album The Natch’l Blues. More recently, the song had gotten a similarly rootsy, but far more direct remake by the Flying Burrito Brothers on Last of the Red Hot Burritos.

“Ain’t That a Lot of Love” is also slow to get started, as most loose jams often are. And yet for all of those obvious caveats, “Ain’t That a Lot of Love” has its lasting charms – principally because of the presence of Helm and Garth Hudson, who simply never give up on it. As Hudson squawks and rolls on his saxes, creating his own Bourbon Tabernacle Choir, Helm’s vocal begins to intertwine with Danko and Manuel’s to form a lonesome train horn.

And it just keeps getting better. In fact, over this take’s second half, after Robertson’s roving turn on the guitar, “Ain’t That a Lot of Love” catches its most assertive groove yet – a reminder of the power of music to bring these now-disparate bandmates together, even if only for a song. Or, really, half a song.

Just like that, however, it was over. Helm was next seen performing “Ain’t That a Lot of Love” with his RCO group on Saturday Night Live. Meanwhile, Banks went onto success writing or co-writing songs like Johnny’s Taylor’s “Who’s Making Love,” the Staple Singers’ “If You’re Ready (Come Go with Me),” Luther Ingram’s “(If Loving You Is Wrong) I Don’t Want to Be Right” and Elvis Costello’s “I Can’t Stand Up For Falling Down.” The Band wouldn’t issue another studio release until the early 1990s – and by then Manuel and Robertson were gone, one to suicide and the other to a separate solo career.

“CHRISTMAS MUST BE TONIGHT”

Composed in the style of scripture during sessions for Northern Lights-Southern Cross, Robbie Robertson’s “Christmas Must Be Tonight” was an ambitious Yuletide gift to his new son Sebastian. Yet it remains a too-often-neglected gem that never became the seasonal favorite it should have been – perhaps because it’s not corny, boozy or jokey enough.

In its way, however, “Christmas Must Be Tonight” represents a canny distillation of what has made the Band such an enduring presence, from Garth Hudson’s spectral colorings, to its spacious cadence, to a Robertson lyric that’s offered from the perspective of a shepherd in that holy moment. “Christmas Must Be Tonight,” and maybe this doomed it from the start, would take on the same kind of emotionally direct underpinning that lifted moments like “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” and “Acadian Driftwood.”

Robertson made another attempt, a decade later, to right the wrong of this song’s relative anonymity, re-recording “Christmas Must Be Tonight” for the soundtrack of 1988’s Scrooged. His solo update also appeared on 1995’s Winter, Fire and Snow: Songs for the Holiday Season, though the absence of the rest of his cast mates in the Band – not to mention a sped-up, more mechanized production in the style of the day – tended to distract from the original narrative’s delicate beauty. Vocalist Rick Danko also subsequently returned to “Christmas Must Be Tonight,” in particular during December solo gigs, but his takes tended to be either simply too raucous or a little too precious.

Instead, the Band version remains definitive, and an obvious highlight on the uneven Islands. Danko’s original lead, as forthright as it is folksy, imbues the song with this humble honesty, while Levon Helm’s second vocal underscores the every-day nature of the narrator’s role as history unfolds.

As with earlier triumphs from the Band like “Drove Old Dixie,” “Christmas Must Be Tonight” tends to bring out personal, rather than general, revelations. The latter, after all, isn’t simply a Civil War song, but also a meditation on lost causes and the sense of duty rooted in home and hearth. Same with “Christmas Must Be Tonight,” a song which, if approached secularly, can also speak larger truths about the promise of birth – that moment when a new world begins inside a child’s eyes.

Perhaps this track was sunk in the end by that very complexity, by aspiring to more than the tinny simplicity of most holiday radio playlists could comfortably accommodate. Whatever the reasons for its fate, the Band’s “Christmas Must Be Tonight” is more than the sum of its seasonal parts. Instead, it belongs in the conversation with some of the Band’s very best work.

“LET THE NIGHT FALL”

I think what I hear on “Let the Night Fall,” as on the more synth-laden moments from the Band’s preceding Northern Lights-Southern Cross, is a group trying to move forward. As celebrated as their journeys back into the American mythos had been, that path ultimately becomes a dead end if you continue long enough. The terminus is at a been-there, done-that moment of freeze-dried ennui.

And so, the Band – granted, in fits and starts – appeared to be turning toward a redefinition, toward something with elements of modernity that might clear the way for new explorations.

It didn’t always work, particularly on the hodge-podge contract-filler that was Islands, but at the same time I think we wrongly ignore what might have been by wishing too much for what once was. They never completed the journey, of course, since this was the last studio album to be issued with Robbie Robertson and Richard Manuel – and that only seems to muddy our perceptions.

The early music is perhaps over-fetishized, the latter-day stuff too quickly dismissed. It’s a shame, in particular when unabashedly lovely things like Richard Manuel’s “Let the Night Fall” become forgotten. It’s not essential, so much as deeply intriguing – the sound of the Band with one foot in their fertile past and another in the then-current melding of pop and soul being fashioned by the Michael McDonald-led edition of the Doobie Brothers.

There is, if you dig deeper, plenty of conjectural subtext. Is Manuel, in the way he sweetly calls for twilight’s comfort, bidding a sad farewell to the Band? After all, by the time Islands appeared, both Danko and Helm had already signed solo deals. The Last Waltz, their much-ballyhooed ’70s-era farewell, was in the editing stage. It was, without a doubt, all over.

Richard Manuel stands, as always, apart – a wise old owl with something important to impart, though (as with many of Robbie Robertson’s best lyrics) we know not what. The Band would, ultimately, disappear surrounded by a similar sense of mystery.

Much had changed for them, in the intervening years – and, in particular, for Manuel, who struggled to regain his muse while his voice became spidered with oaken cracks. As he recedes into that gathering dark on “Let the Night Fall,” brethren encircle Manuel’s still-very-resonant vocal for one of the final times on record. Robertson urgently plucks at his guitar, and Danko’s voice trails behind like the moon’s silvery light. Garth Hudson jabs at his organ, even as Helm unleashes fills that work like a warm summer breeze at Manuel’s back.

Nevertheless, as we now know, that night was most assuredly falling. It’s almost unbearably sad.

- How Deep Cuts on ‘Music From Big Pink’ Underscore the Band’s Triumph - July 31, 2023

- How ‘Islands’ Signaled the Sad End of the Band’s Five-Man Edition - March 15, 2022

- The Band’s ‘Christmas Must Be Tonight’ Remains an Unjustly Overlooked Holiday Classic - December 25, 2016