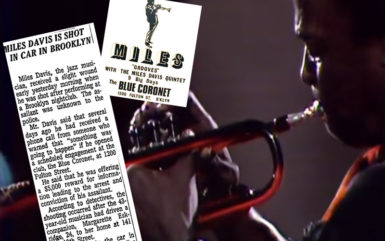

The October 10, 1969 edition of the New York Times included a brief article, sans byline, reporting that Miles Davis had been shot in the early morning hours. While “nicked” near his left hip, the 43-year-old jazz musician’s 1967 red Ferrari suffered worse – though it possibly saved two lives.

Miles had been driving his companion, 24-year-old Marguerite Eskridge, home to 141 East 13th St. in New York City after a gig at Brooklyn’s Blue Coronet club. (The Times spelled her name Margarette.) She was still in the car at the time of the shooting, but was unhurt.

In one telling, three armed men emerged from a “gypsy cab” and fired five shots into the car, one grazing the trumpeter. The Times, while later detailing that three men perpetrated the shooting, stated that “the assailant was unknown to the police.”

Interviewed by Willard Jenkins in 2011 as part of a series on Brooklyn jazz clubs, Dickie Habersham-Bey detailed his time as the owner of the Blue Coronet at 1200 Fulton St. from 1965 to 1985. Habersham-Bey colorfully recalls how Miles would call him to play the Blue Coronet in between touring or recording dates. Davis was booked for a week in October 1969.

In Miles: The Autobiography, Davis wrote: “I later found out that the reason I had been shot was because some black promoters in Brooklyn hadn’t liked the fact that white promoters were getting all the bookings. When I played the Blue Coronet that night, they thought I was being an asshole by not letting the black promoters do the booking.”

Dickie Habersham-Bey framed the era: “There’s always been guys that want to take over the business when they see you doing good business. The week I had Miles – he was working for me regularly. Anytime he had a week off, he would call and say, ‘Hey Dick, I’ll bring [the band] in.’ This guy who was monopolizing the business – he’s dead now, he got shot on Flatbush Avenue – the name is not important. I booked Miles that week … [and] the Village Gate had Gloria Lynne. Now, he made a deal with me to have Gloria Lynne at my place, I told him I couldn’t, so he told Miles ‘don’t show up’ [at the Blue Coronet]. Certain people tried to bulldoze musicians at that time. I looked in the paper and it said Gloria Lynne was gonna be at the Village Gate. This guy said, ‘No, Gloria Lynne’s gonna be at your place.’”

Davis’ attorney didn’t help matters. “There were some threats passed and Miles’ lawyer, Harold Lovette – that bastard knew there was tension,” Habersham-Bey added, laughing. “Harold called [this guy] and told him what to kiss. … See, Harold started everything. They weren’t consulting me, because I knew Miles was going to be at my place, and not Gloria Lynne. Then Harold told that guy what to kiss and said Miles was coming over [to the Blue Coronet] anyway. So over Harold’s BS, this guy wanted to make a point, to show you how bad he was.”

Habersham-Bey regularly reserved two parking spaces in front of the Blue Coronet for Miles Davis, since there were no designated spots. His Ferrari would have been easy to spot.

“So, when Miles left the club, they put the boys on him,” Habersham-Bey told Willard Jenkins. “You know in Brooklyn, it’s very easy to get shooters, even at that time, and they drove up and shot Miles’ car up. When I went down to see the car, if Miles hadn’t had that heavy [car] door, he would have been dead. They arrested Miles for having a couple of reefers on him. Miles said he was never coming to Brooklyn again.”

The Times reported “the police said that while investigating they found a small amount of marijuana in the Davis car, and that he and Miss Eskridge were arrested on a narcotics charge. The charges were later dismissed for lack of evidence.”

Davis offered a different take in Miles: The Autobiography: After the shooting, “we went inside and called the police and they came – two white guys – and searched my car, even though I was the one who had been shot. Then they said they found a little marijuana in my car and arrested Marguerite and me, and took us down to the station. But they let us go without pressing charges because they didn’t have no evidence. Now in the first place, everyone who knows me knows that I have never liked marijuana, never liked to smoke it. So, that was a bunch of bullshit they were trying to hand on me.

“They just didn’t like that a black guy was in this expensive foreign car with a real beautiful woman,” Davis added. “They didn’t know what to make of that. When they looked up my record I guess they found out that I was a musician and had trouble in the past with drugs, so they were going to try and pin some shit on me just for the hell of it. Maybe they would get a promotion for busting a famous nigger. I was the one who called them; if I had drugs on me, I would have gotten rid of them before they arrived. I’m not that crazy.”

Davis’ passenger, Marguerite Eskridge, offers yet another perspective. According to Paul Tingen in a 2001 JazzTimes article on Bitches Brew, her version of events was even more dramatic than Miles’. Both include the fact that the trumpeter had been threatened but, in Eskeridge’s telling, she had some sense of what might happen next.

“He had supposedly been getting calls that he should not be playing there unless he booked through a particular agency,” Eskridge said. “I had a premonition that night at the club that something was going to happen. At one stage, I literally felt blood trickling down the side of my face, even though I was never shot. After the gig, Miles drove me home in his Ferrari, and he kept looking in the rearview mirror. At one point he said, ‘There’s a gypsy cab following us.’ He tried to lose it a few times, and then we pulled in next to the building where I lived in Brooklyn. A few moments later he saw the car coming in from the rear, and said, ‘Duck down.’ We both ducked.

“At that point, a lot of shots were fired from the car, and then it drove away,” Marguerite Eskridge said. “We were still sitting in the car, because I had been taking my time pulling out my keys and everything. If I had gotten right out and gotten up to the outside door, I would have been standing unprotected, and I would clearly have been shot. Miles had been grazed slightly at his side; a bullet had gone through his leather jacket. The car had trapped a lot of the bullets.

“We went to the hospital and at about 5 a.m. the police came out and read me my rights! I mean, we were the victims!” Eskridge told JazzTimes. “They wouldn’t say what we were being charged for, but they took us to the police station, and then finally I found out that they believed that there was marijuana in the car. Later on, all charges were dropped because they found that it was nothing but herbal teas.”

And what of the shooters? There seems to be no follow-up article in the New York Times or in any other publication. However, in his memoir, Davis said he later heard rumors that one of them met a grisly end.

“I offered a $5,000 reward for information on whoever it was that shot me,” he wrote in Miles: The Autobiography. “A few weeks later, I was sitting in a bar uptown when some guy came up and told me that the guy who had shot me had gotten killed, shot by someone who didn’t like it that he had done that. I didn’t know the guy’s name who told me, and he didn’t tell me the name of the gunman who was supposed to be dead now. All I know is what the guy told me, and I never saw him again after that.”

It all adds up to a minor, but telling, story of racial tensions and gritty vendettas involving no-name characters and a very well-known victim. Miles Davis and Marguerite Eskridge would be together for four years, during which time she gave birth to their son, Erin. A partial photo of her face is in a collage on the album cover for Miles at Fillmore, a live album released in 1970.