Some 60 years after the Beatles became a sensation in their native Britain, a book of unseen photographs and new essays titled 1964 – Eyes or the Storm: Photos and Reflections by Paul McCartney was published. He captured a significant period in the Beatles’ history using his newly acquired 35mm camera. As McCartney writes in the foreword, they were images that McCartney vaguely remembers having taken and which had only recently resurfaced in his archives.

Starting in December 1963, McCartney photographed the Beatles, beginning with an ending: being local heroes primarily in Liverpool and London. This was followed by first learning in Paris that “I Want to Hold Your Hand” had raced up the charts to No. 1 in the U.S., followed by traveling to New York to make that historic appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show then performing their first American concert in Washington D.C., and finally winding up in Miami, Florida, for a second appearance on Sullivan’s show.

What’s remarkable about this is that there is no shortage of stories in the media about occurrences that those who weren’t even born until much later might consider ancient history. The reason for this can be found on the back of the book, which encapsulates why we are still fascinated with what McCartney at one time referred to as merely a cool little dance combo: a mention about the book’s essay “Beatleland” by Harvard historian Jill Lapore that cuts right to the explanation …

“… how the Beatles became the first truly global mass culture phenomenon.”

Lapore’s treatise primarily centers on the events of 1964 — including the state of world affairs outside of the start of Beatlemania — but that statement will resonate with those who were old enough to remember just how spectacular that explosion heard around the world affected our collective psyche. The Beatles were at the right place at the right time, and even they weren’t aware of how they would become paragons of popular culture throughout the 1960s, reaching into subsequent decades. The staying power of everything they touched is proof that “global mass culture phenomenon” was not hyperbole.

With a milestone like the Beatles’ 60th anniversary, the plethora of coverage can be overwhelming. Unfortunately, there are few truly legitimate items of merit. One standout is from Vanity Fair photographer Harry Benson, with a title clearly stating the content: When the Beatles Stormed America, I Was With Them from February 2024. Benson describes how he was practically dragged kicking and screaming from a prestigious assignment in Africa and forced to do what he thought would demean him as a “show business” flack. Instead, Benson found that the Beatles were fascinating human beings and not conceited “celebrities,” resulting in images that were memorable, artistic, and even iconic (e.g., the hotel pillow fight).

What’s missing throughout other pieces are the factors that made the Beatles a global cultural phenomenon. When the group first came to America, one question asked by the media was something to the effect of “what is the reason for your popularity?” John reportedly responded, “If we knew we’d form another group and be managers.” It was the kind of snark used for many similar questions that plagued the band, but if John (or anyone) were to actually consider the true answer they would find it wasn’t as simple as a formula. They may have been responsible for the events that led to their impact but there wasn’t any plan that was in their direct control.

From interviews during their first visit to America, it’s clear even the band members weren’t sure if the “mania” was really just a passing fad. When considering the Beatles phenomenon — and make no mistake, it was (and still is) a phenomenon — this can be broken up into two areas: the circumstances behind their explosive popularity, and those that led to their longevity. This article details specific factors and events that would lead to the conquering of the world beyond Europe.

THEIR MUSICIANSHIP: When the Beatles found themselves in Hamburg, Germany in 1960 the members were John Lennon, George Harrison, and Paul McCartney on guitars and vocals; Stuart Sutcliffe on bass; and Pete Best on drums. Sutcliffe was barely 20 years old but they all would grow up fast: their gigs were in the red light district, rampant with seedy clubs frequented by what one might characterize as unforgiving clientele. The tone was set when one manager demanded they “mach schau” — or “make show,” meaning to get on the stage and play for what would be hours on end with few breaks.

According to numerous sources, including Mark Lewisohn’s Tune In (the proposed first of three volumes of their history), they would perform at various clubs practically nonstop for about three and a half months. These were no cushy gigs, as the Beatles found themselves performing constantly, regularly fueled by drugs to remain awake and stretching songs to last as long as 15 minutes. This continuous woodshedding led to their expertise and development as professional singers and instrumentalists.

During the Beatles’ second round in Hamburg in 1961, Sutcliffe left the band to pursue his art studies, and McCartney moved to bass guitar. McCartney’s developing guitar talents would contribute to his melodic bass style, and would eventually impact the composition of their music.

Their acumen as performers developed hand in hand with …

THEIR REPERTOIRE: George Harrison was quoted in Tune In as saying that during this period they learned “a million songs.” This transversed a vast array of musical styles that contributed to their performing prowess while also playing a key role in their eventual songwriting talents. The Beatles would perform the popular music of the day, including basic rock ‘n’ roll, rockabilly, rhythm and blues, country, folk, movie and Broadway tunes.

This constant shifting between numerous musical fashions provided much-needed variety to keep their sets interesting for themselves and their audience, while also becoming deeply instilled into their core. They came to recreate and understand the arrangements and hooks associated with each of those tunes, using guitar lines to replace the parts created by other instruments. They sang both lead and backup, with their R&B influences being chiefly responsible for the call-and-response aspects that would color their music, with harmonies and pervasive oohs and ahhs that were sung under the lead vocalist.

THEIR PRESENTATION: When the Beatles arrived in Hamburg, their appearance was loose and unkempt. Their hairstyles were basically the Elvis Presley-like pompadours that were sported by the popular pop stars of the era. A local college student who was studying photography named Astrid Kirchherr was at first fascinated by their “grubbiness,” as outlined in the obituary from The Guardian. After striking up a romance with Sutcliffe, however, she changed his look. With the urging of her former boyfriend Klaus Voormann and mutual friend Jürgen Vollmer, she then convinced the other Beatles to follow suit.

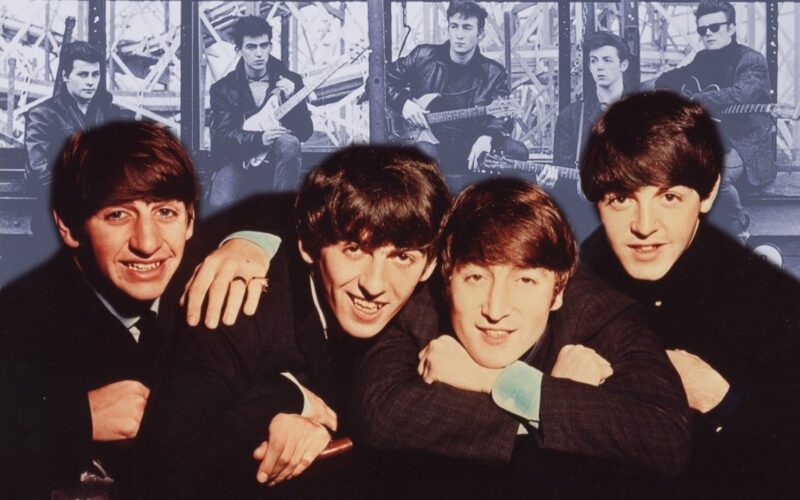

Adopting a more androgynous, bobbed haircut, they became less rowdy greasers and more French New Wave. That look was reinforced by tailored leather jackets and black turtlenecks — “bohemian,” as Lennon would describe it. Kirchherr’s photographs of the Beatles during this period would epitomize their transformation, including the cover photo of their second British album With the Beatles and its condensed American counterpart Meet the Beatles!

(Kirchherr later led Sutcliffe away from the Beatles and back into the art world that first bonded him with Lennon. Unfortunately, after unsuccessful attempts by physicians to treat recurring headaches Sutcliffe would tragically die at age 21 from an intracerebral hemorrhage.)

Later, during a subsequent stint at the Cavern in Liverpool, the Beatles came to the attention of Brian Epstein, whose affluent family ran successful retail shops in the area. Epstein managed the family record shop and thought that his influence would assist in bringing them success. He recognized that their presentation had to become even more prim and proper and had them wear matching suit jackets, dress shirts, slacks, and ties. This was how successful entertainers dressed, and he directed the Beatles to change their attire to become more suitable for the professional concert stage.

RINGO STARR AND GEORGE MARTIN: These individuals stand alone in their contributions to the coming seismic event, but are lumped together here for the sake of brevity. For more on Ringo Starr and George Martin, see my earlier article George Martin’s Lasting Contribution to the Beatles: Let Them Be, where I traced the foundational role both played in the group’s breakthrough recognition.

After a failed attempt at landing a contract at Decca Records, Epstein brought the demo the Beatles produced there to George Martin. Seeing their potential, Martin signed the band to a contract with Parlophone. Prior to this Lennon, McCartney and Harrison had personal and musical issues with drummer Pete Best. Drummer Richard Starkey, under the stage name Ringo Starr, was a fellow Liverpool musician who had occasionally sat in with the Beatles in Hamburg. The three felt it was time to replace Best, and Martin wasn’t keen on Best’s uneven playing. The decision was made to finally make the change and replace Best with Starr.

Martin’s mindset was one not uncommon in his day: If a producer had little confidence in a fledgling artist’s talents, he could make changes as seen fit. Before Best was canned, Martin made it clear to Epstein that it didn’t matter who the drummer was on the tour. He simply wanted a dependable session musician for the recording of the debut single “Love Me Do,” written by Lennon and McCartney. Released in October 1962, the song was pleasant enough, but it lacked any real gravitas and failed to blaze the British charts, peaking at No. 17. Martin felt he had to bring in outside songwriters to provide their material in order to make the Beatles a success.

This fork in the road would be critical to the events that followed. Martin directed the Beatles to record the poppy and saccharine “How Do You Do It,” a song he recognized as a hit but that the group felt wasn’t in their wheelhouse. As Martin indicated in his biography All You Need is Ears (and reinforced in engineer Geoff Emerick’s biography), saying they hated the song would probably be an understatement.

But a relationship between the seasoned producer and novice recording act would be forged: Martin had the power to tell the Beatles take it or leave it — and the latter would have potentially led to a contentious working relationship that might have doomed the association before it had a chance to develop. Instead, Martin did something extraordinary: He told the Beatles if they had something better, then let’s hear it. He was giving them the chance to show that they might have learned from the failure of “Love Me Do” and see if they had what it took to create their own hits.

Their long development as musicians, songwriters, and performers ultimately culminated in this historic moment, paying off with a huge dividend. “Please Please Me” was a spirited piece of work with its fanfare-like intro; innovative harmonies (Lennon sang a tuneful melody over McCartney’s single note harmony); furious rhythm breaks between verses; a call-and-response section that leads to the chorus (“come on”); a bridge where McCartney and Harrison would make their presence known through their backing ahhs over Lennon’s busy vocal melody; slightly changing the main hook before the last verse, where others would have played it safe and not even have dared; and retaining what might have been an error on the final verse where McCartney sings “I never even” over John’s “you never even” which comes across as intentional and giving it the kind of unique disparity that would occur on future recordings (e.g., “I’ll Get You”).

Everything builds to an outro that was dynamic and bracing, resulting in something one was eager to hear again. On top of it all, Starr’s energetically inventive drumming erased any doubt about replacing Best and at this crucial juncture cemented his importance within the band.

“Please Please Me” established the Beatles as something truly unique and original. They weren’t a pop act with one main singer backed by faceless cohorts performing some innocuous material while being directed to go through the motions. They were a rock band of equals with a singular point of view, offering creative musicianship and innovative songwriting. They were determined to bring excitement to their audience with something they could proudly present, and represent as their very own creation.

After recording “Please Please Me,” Martin congratulated the band for having recorded their first No. 1. It was an indication of the masterworks that lay ahead. The Beatles’ growing confidence eventually meant setting their eyes on the biggest prize: Conquering the United States, which even they might not have realized would lead to the rest of the planet – and into the next century.

But they had worked too long and too hard to rush into it. Though they were on a roll, any bigger success had to be on their own terms.

In an upcoming article, Mike Tiano will examine how sudden popularity led to the Beatles’ affecting, and being affected by, musical and cultural behaviors that contributed to their longevity into the 21st Century.

© 2024 Mike Tiano. All Rights Reserved.

- Remembering Billy James: ‘He Was One of the Good Ones’ - May 15, 2025

- ‘Becoming Led Zeppelin’ (2025): Movie Review - March 11, 2025

- Grateful Dead’s Kennedy Center Honors: What Was Missed - January 27, 2025