Living Colour had the same implausible dream as every other rock band – to make the big time – but with the added overlay of race.

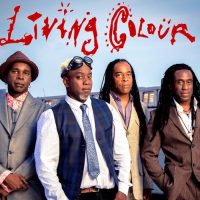

Vernon Reid, Corey Glover, Muzz Skillings and Will Calhoun become funk-metal pioneers, of course, but not without moments of happenstance that Reid still marvels over. Mick Jagger attended one of Living Colour’s regular gigs at CBGB, after Reid appeared as a sessions player on the Rolling Stones frontman’s 1987 solo album Primitive Cool, and became a vocal proselytizer.

This quickly led to a label deal, sessions co-produced by Jagger and Primitive Cool engineer Ed Stasium, and an opening gig on the next Rolling Stones tour. Living Colour’s strikingly inventive debut Vivid streaked into the Top 10 after its May 3, 1988 release.

“That record is such a moment in time,” Vernon Reid told us in an exclusive Something Else! Sitdown. “I remember feeling that working with the band, and working with Ed Stasium, was very much a peak experience – and that was before the record took off. It really was one of the great moments, because it was the culmination of something that seemed impossible.

For Reid, “the fact that we were making the record, period, was amazing. We went from playing in empty rooms, to filling our favorite club CBGBs, to the most famous rock star in the world coming to see us – Mick Jagger. He said, ‘Man, you guys are really cool. How would you feel about recording a demo?’ All of those steps, leading up to the making of the record, it was a fantastic time. With debut records, if you can get out of the way of the music, it can be a magical experience.”

Always interested in history, Reid was acutely aware of how their association with the Rolling Stones fit into a larger continuum. “They championed Stevie Wonder, they championed Billy Preston, certainly a lot of black artists,” Reid said. “Prince opened for them. There were a lot of very cool things over the years. We were thankful to be a part of that.”

None of it would have worked, however, without a foundation of resonant songs. Vivid sold a whopping two million copies as the institutional racism that once followed black musicians who weren’t R&B crooners or rappers was smashed to pieces.

Even the first single from Living Colour’s debut was something of a career-making accident: Their Grammy award-winning No. 13 hit started as a leftover practice-session riff. The song was quickly completed by the end of a session during a burst of creativity surrounding an idea that Reid had involving celebrity, leadership and fame. “Andy Warhol said everybody would be famous for 15 minutes, and I was thinking about that,” Vernon Reid told us.

“Then I was thinking about Jack Kennedy and Martin Luther King and Malcolm X – I could throw Che Guevara in there, too – and they were all very handsome,” he added. “They had important things to say, they were important politically and socially – but they also look like matinee idols. The fact that they look that way is part of their appeal, yet it can never really be spoken of. That’s too shallow, not very deep. But the fact that they all looked like stage actors, that they all have iconic good looks, that’s a part of their mystique.”

Then Reid began thinking about “the other side, the Hitlers, the Mussolinis. They also have an appeal, but from a different direction. I thought to myself: ‘There’s something that’s unifying in the two things – something beyond good or evil.’ I just proceeded from that point, with this Nietzschean idea. I wasn’t writing about duality, in the sense of good versus evil. I was writing in the sense of good shakes hands with evil, shakes hands with good. That’s the thing from the first line: ‘Look in my eyes, what do you see?’ What do you make of it, you know?”

Living Colour quickly became the faces of a new brand of inclusion, and they leveraged their groundbreaking status through work with the Black Rock Coalition.

In many ways, that’s become the most important part of their legacy, despite the platinum-selling successes of Vivid. Vernon Reid says he looks out, and he sees that impact every day. “I think the needle has moved, but not nearly as much as it needs to,” Reid told us.

“When I think of the tapestry and the culture that we helped to create, I’m proud. Rage Against the Machine happened after us, TV on the Radio – that would have been unimaginable,” Reid added. “They make hugely different music, but I’m proud that in some way – maybe in an infinitesimal way – we were part of the way certain things unfolded.

“Similarly, we wouldn’t exist without the Bad Brains,” Reid said. “We wouldn’t exist without a lot of other bands that are completely forgotten. This is just the way it is. Now, there’s a sense of community that’s extended, say, into Afropunk. They are doing what they do in a very different way, but it’s great to see the way it’s expanded.”

- The Bright Spots in George Harrison’s Troubled ‘Dark Horse’ Era - December 29, 2024

- The Pink Floyd Deep Cut That Perfectly Encapsulates ‘The Wall’ - November 29, 2024

- Why Pink Floyd’s ‘The Endless River’ Provided a Perfect Ending - November 11, 2024