Revolver represented a huge leap forward for the Beatles, as explored in an upcoming expanded reissue. But that revolution in sound actually began with a couple of its bonus tracks: The single “Paperback Writer” and “Rain,” released months before, ushered in major changes in songwriting, instrumentation and recording.

The two songs were recorded in 1966 over April 14 and 16, as detailed in the two meticulously researched books on the Beatles’ musical output written by Mark Lewisohn (The Beatles’ Recording Sessions and The Complete Beatles Chronicle). Sessions for Revolver had recently begun, and the tracks were preceded by work on tracks that included “Tomorrow Never Knows,” “Got to Get You into My Life” and “Love You To.”

The acapella intro that opened “Paperback Writer” was one of the first for the Beatles, following “Nowhere Man.” Apparently the band had heard an advance copy of the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, and that inspired Paul McCartney to craft that chorus. The guitar riff that followed contained more distortion than previously heard on a Beatles song, and while some credit George Harrison, it was actually Paul playing his Epiphone Casino guitar on the recording.

The real eye opener here was that at the end of the riff Paul’s bass line kicks in with a sonic ferocity that had not been heard on the Beatles’ tracks until this point.

The Beatles wanted to emulate other artists’ recordings (particularly those from Motown) where the bass was not buried, as theirs had been. Engineer Geoff Emerick revealed to Lewisohn that Paul set aside his signature Hofner and instead played a Rickenbacker. Photos of the session show that the model was a 4001S, a left-handed version of the same model closely associated with Chris Squire, the late bass player for Yes.

(One photo from the session shows Paul playing the Casino with George playing a Nu-Sonic bass. A source said it was taken during the recording of “Rain,” though Lewisohn in Recording Sessions notes that Paul overdubbed his bass lines on “Rain” two days after the photo was taken. Others have suggested that George’s bass was used on the song regardless of who played it, but Emerick – who was at the session – said that Paul played the Rickenbacker. The most credible explanation (though still unconfirmed) was that George played the bass on “Paperback Writer” while the band was working out the song, with Paul later overdubbing the Rickenbacker. Their positions in the photo seem to bear this out, as they aren’t arranged as if they were about to record.)

Other innovations allowed the bass on this Beatles recording to be prominently heard, including the use of a loudspeaker as a microphone, and adopting a new device from EMI’s technicians that allowed the Beatles to produce and release the label’s first high-level master lacquer cut without, as engineer Tony Clark told Lewisohn, “[making] the stylus jump” on turntables. (Emerick discusses these techniques at 5:45 in the YouTube video below.)

Recording advancements weren’t the only major change for this single. The Beatles’ lyrical content had evolved in their original songs. During the Beatlemania honeymoon period, their first three albums were mainly centered on basic “I love you” themes. As fame started to take its toll, the songwriting for subsequent LPs took a darker turn.

Tracks from this period included “Baby’s in Black” (her previous lover may be dead), “No Reply” (where the protagonist appears to be a stalker), and “Run for Your Life” (“I’d rather see you dead, little girl, than to be with another man”).

From the lyrical standpoint, one song on Rubber Soul was a precursor of sorts to the single at hand: “Nowhere Man” was the first original Beatles song that had nothing to do with love or relationships, good or bad — at least overtly. It could be suggested that the subject was becoming a “nowhere man” due to a downturn in a relationship, but there is nothing in the lyrics that elevate this beyond conjecture.

“Nowhere Man” was an album track that was issued as a single in the U.S. in February 1966 after Rubber Soul was released in December 1965, even though the Beatles made every effort to keep singles and album tracks separate. (It wasn’t released as a single in the U.K.) “Paperback Writer”/“Rain” was the first Beatles single where not just one but both sides of the disc did not address romance in any form.

The lyrics in “Paperback Writer” appear in the style of a letter being written to a publisher asking for a job (“Dear sir or madam, would you read my book…”). The protagonist wants to write the type of sordid stories that appeared in Signet books at the time (“…a dirty story of a dirty man and his clinging wife doesn’t understand”). The relationship described in the pitch could be autobiographical, with the letter writer “working for the daily mail” and he may be describing his own parents. But as the remainder of the song centers on the pursuit of getting “a break,” the relationship described isn’t as important as the pursuit of becoming a paperback writer.

It’s widely known that during this era the mono mixes were important, as they would mainly be heard through a single speaker, with the stereo versions being almost an afterthought. Rubber Soul, in particular, is a prime example of the latter: Practically the entire stereo album placed the vocals on one side and the instruments on the other. (The late George Martin attempted to rectify that somewhat when the songs were later remastered for CD.) For “Paperback Writer,” the stereo version reveals minor items that were obscured in the mono mix but can be heard with careful listening on the stereo edition.

These all occurred during tracking the vocals:

• 0:57 – A cough is audible (but easily missed if one was not listening for it).

• 1:46 – It sounds like one of the singers is expelling a breath.

• 1:48 – Paul (?) can be heard singing the word “paperback” to himself in advance of his part. This could have been to prep in advance of singing the part, or an artifact of another take.

One erroneous myth perpetrated by some is that “Paperback Writer” consists of only two chords (G7 and C7). That is only true for the verse, as there are four underlying chords during the chorus (albeit muted). These were played on the recording as a guide for when Paul, George and John recorded their vocals with the instruments later removed. (When the song was performed live on the Beatles’ last tours, they played the chords, again as a guide). The chords appear to be C – G – Am7 – D7. This chord structure contributed to the song’s distinctiveness: technically the song is in the key of G but the intro kicks off with a C, so when the verse follows with the G7, there is a sonic divisiveness that is subconsciously startling.

There is one mystery in “Paperback Writer” that has not been solved. During the third and fourth verses, John Lennon and George Harrison are singing “Frère Jacques” as backing vocals. Why was this French children’s song chosen? When asked about this in interviews, Paul doesn’t seem to remember (including this article in Billboard from November 2015). Others have surmised that it was a nod to John’s writing efforts (In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works).

But this author has a theory that might be the most plausible, and one that doesn’t appear to have been suggested, as far as I know. The chorus could be perceived as a round, of sorts. A round is defined as “a canon where the melody is sung in two or more voices. After the first voice begins, the next voice starts singing after a couple of measures are played in the preceding voice.” “Frère Jacques” is a good example of this. While the chorus for “Paperback Writer” doesn’t literally fit the definition, it still might have reminded one or more of the Beatles of how that children’s song was sung, and added for that reason. (Attempts to reach Paul McCartney to consider and possibly confirm this theory were unsuccessful.)

As mentioned, John Lennon’s “Rain” matched “Paperback Writer” in content and execution. Again, the lyrics had nothing to do with romance in any form: This was John saying to his fellow precipitation-hating Britons that the weather was “just a state of mind.” Whether it bothered anyone or not was more about the perception rather than the literal state of it.

From a production standpoint, there were some different techniques used on “Rain.” One was to play the backing track fast then slow it down to give it a different feel (changing the “texture and depth,” as Emerick told Lewisohn). Once the slower take was captured, it would be used for playback during the recording. As Emerick pointed out, it would have been more difficult to work on the track at actual speed then slow it down each time a playback was reviewed. The song does have a drone-like, dreamy quality that isn’t unlike the first versions of “Mark I,” the working title of “Tomorrow Never Knows.”

While the Beatles’ performance on “Paperback Writer” was fairly straightforward — there, the verses were all played the same with little variation — on “Rain,” there were two distinctive changes that were unusual not only for the Beatles but for rock music in general.

One was Paul’s bass line on the two bridges (“Rain, I don’t mind; Shine, the weather’s fine”), over the words “rain” and “shine.” The first time Paul plays a repetitive figure of two notes where he’s sliding from one note to the root for each beat (starting at 1:02 in the instructional video below). The second time, Paul is playing three notes over two beats (these are triplets, starting at 1:50 below). Perhaps Paul was playfully suggesting that each of the two represented different rain patterns. It’s worth noting that Paul’s bass lines are also different on the verses, though those differences are more subtle.

The second deviation from past Beatles songs was Ringo Starr’s uncharacteristically busy drumming. His performance on this recording is the antithesis of playing it straight. On the verses, he’s throwing in fills and rolls wherever inspiration hits, while on the bridges he lays back at those same aforementioned points where Paul played the different rain “patterns.” One could speculate that these were Ringo’s own take on the changing rhythms of falling rain. While it’s possibly the most frenetic drumming Ringo has ever done on a Beatles song, it fits in perfectly with the proceedings. It’s also a wonderful example of how innovative and creative the Beatles drummer actually was, something that is easily overlooked when compared to other, more technical percussionists.

Lennon’s backwards vocals on “Rain” are another first. There were questions about that which have been a source of confusion: whose idea was it, and was “Rain” the initial Beatles recording where this was used?

As to who was responsible for the idea of using a backwards track, Lewisohn mentions either George Martin or John Lennon in Recording Sessions. David Sheff quotes John in his book All We Are Saying as saying he got the idea after returning from a session one night. On his home recorder, Lennon threaded a tape that contained a copy of what they recorded at the session that evening, not realizing that he probably threaded it inside out. The result was a backwards playback. John, being high on cannabis, said he was astounded by what he heard – and that led to incorporating the backwards singing on “Rain.” But Martin told Lewisohn that it was he who was the responsible party on “Rain,” based on the Beatles’ thirst for experimentation during that time.

Another related question is: When was this technique first used by the Beatles in the studio? Days before the start for production of “Rain,” the Beatles had begun working on “Tomorrow Never Knows.” Loops were used on that tune, which also included a backwards guitar solo. Some sources list the “Rain” sessions on April 16 as the first to use backwards recording, with the “Tomorrow Never Knows” solo recorded on April 22.

On the latter date, however, Lewisohn states that George Harrison recorded a “whining” sitar part, and specifically notes the backwards guitar solo on “Tomorrow Never Knows” was previously recorded on April 6. That indicates the solo for “Tomorrow Never Knows” was both recorded and reversed on the same day, making this the first time a backwards part was used. “Rain” would be the first release where that technique was heard publicly (since “Tomorrow Never Knows” was slated for Revolver, released months later).

Those questions aside, the backwards vocals weren’t obvious to consumers. When the single was released this author (as well as many others) thought they were sung straight, the lyrics being something to the effect of, “Spread her down and love is coming near” as they sounded like actual words. Of course, even if that were to be true, it was absurd since that mistaken line had nothing to do with the song’s subject.

Simply put, John sang the following, which Martin reversed for the recording: “Sun shined … rain … If the rain comes, they run and hide their heads.” (Note that on this YouTube capture it sounds like “sun shined” instead of “sunshine” as the “d” on the second word is clearly pronounced.)

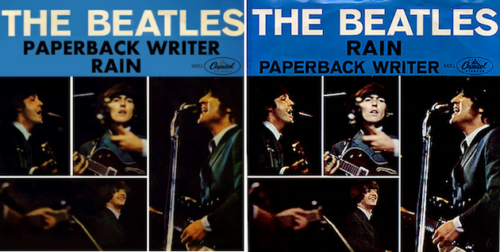

It had been a while since they released their previous single, “We Can Work It Out/Day Tripper” in December 1965, so the Beatles were overdue for a new one. “Paperback Writer” and “Rain” were chosen as their single of 1966, and were released in the U.S. on May 30; the U.K. release followed on June 10. “Paperback Writer” has been considered the A-side, not surprisingly as it is the more spirited and catchy of the two. However, the picture sleeve listed it first on one side and second to “Rain” on the other. If Mark Lewisohn is the final arbiter, then the appendices for Chronicle book lists “Paperback Writer” alone in the lists for the Beatles’ Peak Singles, sandwiched between others that were listed as actual double A-sides (“We Can Work It Out”/”Day Tripper” and “Eleanor Rigby”/”Yellow Submarine”).

While the single quickly shot up both the U.K. and U.S. charts, it lasted only one week at No. 1. Lewisohn notes that it was the Beatles’ lowest-selling single since their very first, “Love Me Do.” At this point in their career, the Beatles were blazing through new trails, turning their attention to increasing the creativity of their music and recordings in light of seeing the end of exhausting and unproductive touring — and it might have take a while for the public to catch up.

One can surmise that the content of these two songs caught the fickle female records-buying public by surprise, and after hearing the songs on the radio were not as interested in purchasing a single where the subjects were about a desperate job hunter and the weather – instead of, well, the girls themselves.

The promotion of the single resulted in two separate filming sessions for each of the songs, all directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg, who would later helm Let It Be: one with the Beatles wearing sunglasses and miming to the songs in the studio, with the other filmed at the Gardens at Cheswick House without instruments. In the latter, sometimes they lip synched with only guitars present. (Ringo didn’t even pretend to play.) Other times, they did nothing more than stand around looking bored.

These films can be found in the Beatles video compilations 1 and the extended version, 1+, which were both released in 2015. An animated project titled The Beatoons (not affiliated with the Beatles or Apple) offers an amusing take on why the Beatles wouldn’t sing during the filming at the Gardens at Cheswick House.

Many years later, Paul McCartney demonstrated that he still had affection for “Paperback Writer” by regularly performing the song on stage.

Paul has also shown that as a member of the Beatles he has no problem performing songs that were sung (and even written by) John Lennon and George Harrison – including “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!,” “Something,” “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Please Please Me.” Maybe McCartney will surprise us all and perform “Rain” along with “Paperback Writer” on a future tour, in recognition of a stand-alone single that showed Beatles were going to amaze everyone with even bigger surprises to come.

Updated October 2022. ©2016 Mike Tiano. All Rights Reserved.

- Remembering Billy James: ‘He Was One of the Good Ones’ - May 15, 2025

- ‘Becoming Led Zeppelin’ (2025): Movie Review - March 11, 2025

- Grateful Dead’s Kennedy Center Honors: What Was Missed - January 27, 2025