When I grew up in Inglewood, Calif., during the 1960s there were only a couple of stores that sold records close to home. There was Inglewood Music on Market Street, an all-encompassing music store that sold both records and instruments, and provided music lessons.

But the hip place to go was just around the corner on East Nutwood Street: Crane’s Records. This is where I bought my first “real” acoustic guitar, a knockoff of a Gibson Hummingbird with the Memphis brand on the headstock. That instrument replaced the Blue Chip Stamp axe my mom obtained for my brother Al but which ended up in my possession after I decided to self-teach myself the instrument. I did that by tackling the contents of a songbook purporting to contain all the songs recorded by the Beatles. (I still have both the Memphis and the dog-eared book, the latter sans cover and split into two halves.)

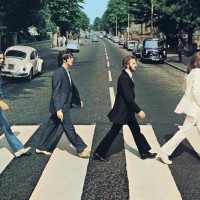

While Crane’s sold a limited number of instruments, their part and parcel was the sale of records. Whenever I learned of a forthcoming release by the Beatles (and later Led Zeppelin, or the Who) I would hound the store’s employees by phone or in person every single day until I was informed that the album in question was finally available for purchase. That was the case for Abbey Road. Being a Beatles fanatic even as a teenager I already knew that this new album was going to be released ahead of what was to be titled Get Back, the infamous Beatles sessions later to be rechristened as Let It Be.

In late 1969, when I found out Abbey Road was available at Crane’s, I was delighted to learn that it was the British release, days before the official one for the U.S. While Capitol Records in the U.S. had butchered every U.K. Parlophone release up until Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), for Abbey Road the only difference for this latest album was the glossier cover on thinner cardboard.

I was with a friend when I bought Abbey Road at Crane’s, and we rushed back to his house to listen to it. It wasn’t until quite a few minutes into the ending of “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” that we began to wonder why it was taking so long for Side 1 to finish. We then realized that a defect in the vinyl was causing one passage to repeat over and over so perfectly to where it appeared to be seamless. Since we were hearing it for the first time, there was no way of knowing there was a problem until we could see the needle stay in one place for what seemed like forever.

After obtaining a replacement and repeatedly digesting the entire album in its entirely, I was mesmerized by Abbey Road, and why wouldn’t I be?: It was the Beatles after all, with a set of songs that were stellar.

The latter half of Side 2 introduced me to the concept of the medley, something I’d not encountered before. That medley — or, “The Long One” as it is informally titled in the book that accompanies the new 2019 rerelease of Abbey Road – dominates the last portion of the album, starting with “You Never Give Me Your Money” and ending with, appropriately “The End.” Starting with “Sun King,” there were a series of songs by John Lennon and Paul McCartney that were in various stages of completion. Rather than flesh them out as individual tracks, they patched them together into one larger piece.

(The rerelease also returns “Her Majesty” to “The Long One,” since that segment was originally to be slotted between “Mean Mr. Mustard” and “Polythene Pam.” When the placement there didn’t work for the band, “Her Majesty” was cut and temporarily placed at the end of the master tape. When the Beatles heard it come on at the tape’s end, they decided to leave it there for the final release.)

But I was a bit taken aback at something that occurred during “Carry That Weight”: parts of “You Never Give Me Your Money” were being repeated. It’s embarrassing to admit now, but at the age of 16 I initially wondered why the Beatles had to reuse parts from another song. Surely, they could have been original and written something new!

I came to not only accept but eagerly embrace what was one of the earliest examples of a genre for which I became a major proponent throughout the 1970s: progressive rock. The word progressive accurately describes the form. This term wasn’t derived from the virtuosity of the musicians, or the different styles that might be touched upon throughout a given composition, or even the often-longer lengths than the average pop ditty. A progressive (or in its shortened form, prog) rock piece unfolds, or more to the point, progresses – hence the genre’s classification.

A major component of this category is the repetition of themes, which in musical terms is known as a recapitulation. Tied to that is the occasional use of reprises. These are major factors in how the composition develops in most prog-rock compositions, and there is some overlap and differences for the two terms. A reprise is usually a song repeated with only minor variations. Recapitulation is the restating of various themes later in the work in a markedly different way.

The Beatles had memorably employed a reprise once before. The concept of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was that all of the tracks were part of a live performance, so the title track was reprised. (The word was even part of the song’s title.) The band thanked the audience for attending the “show,” before ending with the masterful “A Day in the Life.” In that case, it was the actual song that was reprised, rather than its parts appearing in an altogether different track.

On the other hand, the first rock band to use the recapitulation in an overarching way was the Who, with their epic Tommy (1969), which was touted as the initial rock opera. Several passages are restated throughout the album, both instrumental and lyrical. (For the latter, the most effective was “Listening to you, I get the music…,” which in itself might be termed a reprise.)

Not long after the release of Abbey Road, many artists of the era who weren’t pigeonholed as being “progressive” attempted their own take on using themes to bookend and/or link sections of some of their compositions. Early examples include David Bowie’s “The Width of a Circle” (The Man Who Sold the World, 1970), Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” (Led Zeppelin IV, 1971), and Pink Floyd’s title tune from Atom Heart Mother (1970).

One wouldn’t have thought that Jimi Hendrix would have used these concepts, but he did a masterful job on the last studio album he released before his unfortunate passing: Electric Ladyland (1968). That album hints at subsequent, unrealized heights which might have possibly included the reprises and recapitulations that he (maybe not) surprisingly presented on that release. The long, slow, bluesy “Voodoo Child,” found toward the start of Electric Ladyland, was reprised in the last track – the searing and intensely brisk rock and roll of “Voodoo Child (Slight Return).” But he didn’t stop there. The dreamy “Rainy Day, Dream Away,” which opened the Side 3 on vinyl, concludes with a very brief portion of “Still Raining, Still Dreaming.” That, in turn, quickly fades but returns in full at the start of Side 4. (In a tribute to that concept – and to Hendrix, who was extremely influential to me as an artist — I do something similar on my forthcoming album Creétisvan.)

But progressive rock bands were the artists who consistently recognized that using recapitulations and reprises would expand their listeners’ horizons and set them apart from more conventional rock artists. One of the best examples are the three pieces from Yes’ fifth album, Close to the Edge (1972) – in particular the title track from that album, which was their first piece to take up an entire side of vinyl.

Other opuses beat Yes to the punch, but “Close to the Edge” (the composition) had one huge advantage that catapulted it beyond the other long form pieces before and since: The use and reuse of reprises which made an almost 20-minute track deceptively accessible.

In most long-form progressive pieces, the musical content can be varied and disparate when reprises occur. In the case of “Close to the Edge,” its simple structure is not only instrumental in how the piece builds, the reprises follow a definite pattern: Reinforced themes led to a familiarity that doesn’t lose the listener by going off into unfamiliar passages. (Disclaimer: I wrote the liner notes for the 2003 Rhino remaster of Close to the Edge, and the comments here might resemble those notes.)

“Close to the Edge” is listed as being in four movements. The first, “The Solid Time of Change,” is structured in two parts: a chant-like section is followed by a more melodic segment, and the two are linked by a section that includes the piece’s title. This same basic structure immediately follows in “Total Mass Retain.” While there are elements in common with the first movement, however, Yes changed components and even introduced an instrumental passage that’s recapitulated just before Rick Wakeman’s organ solo late in the composition.

The structure in the first two movements is given a rest when the previous lines “I get up, I get down” are recapitulated in an altogether different manner for the ethereal movement of the same name. The aforementioned two-part structure is then reprised at the conclusion of the last movement “Seasons of Man,” in a manner so dynamic and heightened that this last reprise packs an emotional wallop — and that impact was only possible due to the familiarity of what preceded it.

While other Yes pieces effectively used reprises and recapitulations, the band wisely didn’t duplicate the repetitions of the movements – and this simple structure is likely a big reason that “Close to the Edge” is recognized both as Yes’ best long-form piece and a shining example of progressive rock at its finest.

Yes might have been feeling overconfident when they created the ambitious follow-up Tales from Topographic Oceans (1973), which contains a number of themes that are recapitulated. I also wrote the liner notes for the 2003 Rhino remaster of that album, and as I stated there, I believed this was the album that separated the casual listener from the true believer. Those who put themselves in the latter camp will enjoy the many examples of recapitulations in the four expansive, side-long (on vinyl) movements.

While the album is too sprawling to analyze here, there is one humorous example of the use of recapitulation worth noting: In “Ritual,” guitarist Steve Howe revisits themes presented throughout the album, and at one point he throws in the main theme from “Close to the Edge.” (On that album, the original theme follows the intense instrumental introduction, and directly precedes the “The Solid Time of Change.”) Thus, he’s actually recapitulating a theme from an entirely different album.

Other prog bands of the era found their own ways to incorporate recapitulations and reprises. Emerson Lake and Palmer’s “Tarkus” (from the album of the same name, 1971) consists of a series of songs that are joined together by a recurring instrumental theme. While that is the one common motif that links the songs together, there are other themes that are more subtly reintroduced.

If there was any one band that took the use of recapitulation farther than the others, it is Genesis. An early example of their own usage in a long-form piece is “Supper’s Ready” from Foxtrot (1972). Unlike “Tarkus,” there is no reoccurring link between sections to foster familiarity. By the end of the piece, the listener might be lost in all the changes if not for the way the song progresses, and the joining of two main themes introduced at the onset: “Hey babe … don’t you know our love is true” and “Can’t you feel our souls ignite.”

What follows the introduction of those refrains consists of a long stretch that does not include the reuse of any other themes, but the voyage comes full circle when the two items are dramatically reintroduced and juxtaposed at the conclusion of the piece. It’s similar to the conclusion of “Close to the Edge” in how the tempo and instrumentation delivers an emotional finish.

On subsequent releases, Genesis took recapitulations and reprises well beyond “Supper’s Ready,” even presenting themes in an entirely separate composition. When it came to the usage of those concepts, they are the winners hands down, along with guitarist Steve Hackett in his solo work. (Those alone will be covered at greater length and depth in a follow-up article, illuminated by comments from Hackett himself.)

There are many other examples of the use of reprises and/or recapitulations in prog within the same piece, as numerous artists adopted them throughout the era. Pink Floyd’s The Wall (1979) repeated themes throughout in a manner similar to the refrains used in Tommy. Other effective uses of the concept include Emerson Lake and Palmer’s “Pirates” (from Works, Volume I, 1977), “March of the Black Queen” from Queen II (1974, a track that acts as almost a dry run for “Bohemian Rhapsody”), Rush’s Hemispheres (1978), and even the Grateful Dead’s side-long title piece from Terrapin Station (1977).

One particularly notable composition that demonstrated stellar usage of these concepts is “Song of Scheherazade” by Renaissance, from Scheherazade & Other Stories (1975). On occasion prog has been categorized as “symphonic rock,” but Renaissance has come closer to that categorization than the aforementioned prog bands: the addition of an actual orchestra on “Song of Scheherazade” presents a shining example of being symphonic, in both the structure and the usage of reprises and recapitulations.

The opening “Fanfare” contains a theme that is alluded to in the very end of “Finale.” Many items from the second movement “The Betrayal” are recapitulated in “The Sultan,” “The Fugue for the Sultan,” and “Finale.” “Love Theme” is introduced with an evocative piano solo followed by a haunting orchestra arrangement, and subsequently recapitulated with a vengeance towards the end of “The Festival.” (Genesis later used the first portion of that very same theme for Mike Rutherford’s guitar solo in “That’s All” from their 1983 album eponymously titled Genesis; it’s unknown whether this was intentional or just a coincidence).

The reprise at the conclusion of “The Finale” ends with Renaissance vocalist Annie Haslam hitting a note so high that she’s in danger of only dogs being able to hear it. I’m joking, of course, but it is almost otherworldly, and a fitting cap to the conclusion of a dense and rewarding composition.

For Abbey Road, the restating of the “You Never Give Me Your Money” themes during “Carry That Weight” may not appear to be as weighty as the ones used in the more involved pieces mentioned here. But while brief in comparison, the use of recapitulation on “The Long One” is nevertheless effective in tandem with the orchestration, especially when an instrumental version of the “All good children go to heaven” segment reappears momentarily right before “The End.”

My own journey of appreciation for recapitulations and reprises began with that Beatles medley, which led to rich musical experiences that others may have also discovered, or will uncover by exploring the pieces mentioned here — and I’ve barely scratched the surface. Feel free to list your own favorite pieces using those concepts, in the comments section below and/or at my music page on Facebook, where I will post a link to this article.

Special thanks to Jonathan Sindelman and Rick Daugherty for their help with the usage of the musical terms used in this article. © 2019 Mike Tiano. All Rights Reserved.

- Remembering Billy James: ‘He Was One of the Good Ones’ - May 15, 2025

- ‘Becoming Led Zeppelin’ (2025): Movie Review - March 11, 2025

- Grateful Dead’s Kennedy Center Honors: What Was Missed - January 27, 2025