[Author’s Note: If you haven’t seen ‘Vertigo,’ be aware that this article doesn’t just contain a major spoiler. The article is actually about that spoiler. Before embarking on this little known behind-the-scenes journey into an Alfred Hitchcock classic, please watch the movie first.]

It was April 1958 where, in a screening room at Paramount Pictures, Alfred Hitchcock was preparing to decide whether to cut a key scene from his soon to be released film — the one Hitchcock film that would go on to be hailed many years after its initial release as one of the greatest motion pictures ever made.

Of course, that movie was Vertigo. On this spring day, Hitchcock was joined by studio executives, colleagues, and members of the cast and crew to screen a new cut of the film that didn’t include the one sequence that was a source of contention between certain individuals present, with Alfred Hitchcock caught in the middle.

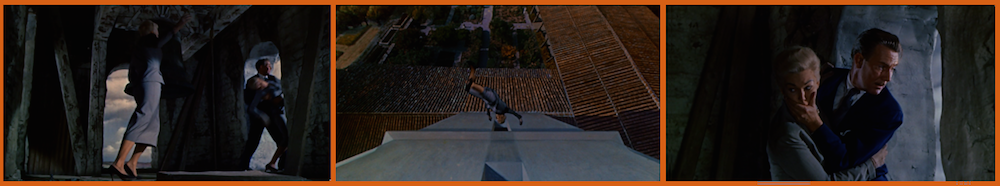

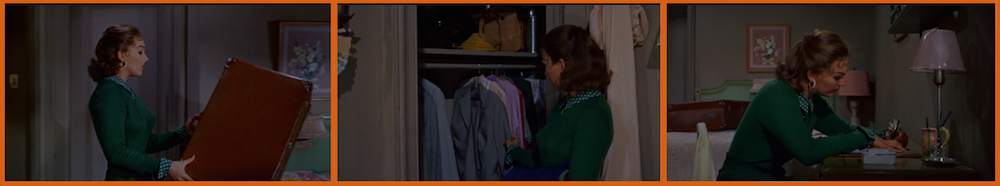

The issue at hand was whether to include a plot point I called the Big Reveal, where the audience is given information late in the picture that changes what they thought to be true. In this case, it was the revelation scene, where the viewer learns what actually happened at the bell tower, well before the film’s conclusion a half hour away.

(Long story short: In a flashback sequence, we learn that the person detective Scottie Ferguson—and we—believed to be Madeleine, the wife of old college acquaintance Gavin Elster, was actually Judy Barton, recruited by Elster to be made up to look like the real wife. This ploy enabled Elster to take advantage of Scottie’s vertigo, preventing the detective from following the decoy through a trap door at the top of the bell tower, where Elster was waiting to throw off his already-murdered wife as Scottie witnessed the alleged suicide through a window from the stairway.)

Alfred Hitchcock wasn’t one to compromise, but in an effort to both appease the studio and to determine if it wasn’t such a good idea to reveal the secret early on, he screened a version of the film that did not include that crucial scene to see if it played better — leaving the secret to be exposed through the existing dialog in the closing minutes of the film.

It would be perfectly reasonable to conclude that given the film as we know it, this screening confirmed that the last act was problematic with the sequence excised, and to assume that Vertigo was released with the revelation scene intact.

Surprisingly, that was not the case. The actual decision was to remove that scene entirely, and it wasn’t settled without a great deal of heated discussion between the screening’s participants.

With the choice to excise the entire sequence agreed upon — starting with Judy Barton’s flashback and ending just after she tears up the confession — Vertigo went to the film labs for processing with that scene eliminated, where the final reels would be created then shipped out to theaters worldwide.

The story behind this decision — including why Alfred Hitchcock may have gone along with it and how, at the last minute, the scene was reinserted into the final print — was only known (and even forgotten) to the people involved with the original production. That is, until Dan Auiler stumbled across some discrepancies in the film’s timing logs while researching his first book, Vertigo: The Making of a Hitchcock Classic, the realization of a long-time dream.

As a journalist in Texas, Auiler discovered his passion for movies, writing film reviews for a small town weekly. He eventually put his writing aspirations on hold when he moved to California to earn a living as a high school teacher specializing in drama and journalism. Fifteen years into that vocation, Auiler realized that as an instructor he was losing touch with the art of writing. This resulted in his decision to write a book, as Dan Auiler puts it, “on the one film that I would write about, even if I could not find a publisher for it — if it was a vanity project I would not consider it a waste of time … and ‘Vertigo’ was that film.”

So, in the summer of 1996, Dan Auiler began visiting the Margaret Herrick Library (where the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences holds its archives) to perform research for this book. Although Auiler had considered other movie-related projects (e.g., writing a screenplay), it was feeling a sense of urgency that led him to choose uncovering the backstory for Vertigo: Auiler knew that many of those involved in the film’s production had passed on, along with their oral history that would have illuminated the book. However, he could interview the surviving participants to obtain stories and anecdotes that one wouldn’t expect to find in the Herrick Library.

Unbeknownst to Auiler, his timing for embarking on this project couldn’t have been more serendipitous. Shortly after beginning his research Auiler sent out his proposal for a comprehensive examination of the making of Vertigo, not knowing it was coinciding with the release of that film’s major restoration by Bob Harris and James Katz. Within three days of obtaining an agent he landed a publishing deal with St. Martin’s Press. Even though Auiler was skilled at the art of writing, this was his first book. He credits his editor Cal Morgan for helping with the flow of the materials and the St. Martin staff for the book’s overall design. “In a way,” Auiler says, “it set the standard for how certain film books for all movies should look.”

Though Dan Auiler would find many fascinating facts about the production, he came across one that would trump anything else he discovered. It happened while examining the dialog-cutting transcripts, which contain the dialog text for each reel and are used for post-production tasks (e.g., looping): He saw that before May 1, 1958, the film’s running time had shifted from 2:07:05 to 2:03:05. But when he found a transcript from just after May, 1 — less than a week before Vertigo was to premiere in San Francisco — Auiler noticed that the movie was now back to being four minutes longer.

It was in reading the dialog in those transcripts that Auiler identified the missing four minutes: the revelation scene.

Up to this point, Dan Auiler knew nothing about the running time changing within one week — not only before he began the project but even when initially interviewing the surviving participants, including Herbert Coleman. Coleman was a longtime associate of Alfred Hitchcock’s starting with Rear Window, and was the associate producer on Vertigo. “It was a big surprise,” Auiler recalled. “In fact, it was the easiest thing to miss in the oral history.”

After discovering this fact, Auiler went back to Coleman to ask if he remembered the story behind this, and it was at that time Coleman recalled that screening where the big decision was made. Auiler learned that Coleman got into a heated argument about this scene with Alfred Hitchcock. In the end Hitchcock prevailed: the revelation scene was cut, and the final print was sent to the labs for processing.

“I do remember talking to Samuel Taylor about the same issue,” Auiler recalled. “My question was, was there any question during the writing as well, as to whether the scene should be in there or not.” Auiler was fortunate to have also interviewed Vertigo screenwriter Taylor. Alec Coppel had delivered a first draft containing a number of problems so Taylor — who had written a number of other films, including Sabrina, starring Humphrey Bogart and Audrey Hepburn — was hired to rewrite Vertigo.

Taylor told Dan Auiler that there was never any question about the scene during the writing process; the editing stage of filming was another matter altogether. “He thought for a long time and he got back to me and he said, ‘I sort of remember Hitch getting cold feet’ … and [Hitchcock] saying to him that the studio wanted that section gone, and also wanted a section at the end explaining what happened.”

According to Auiler, prior to that screening Paramount Pictures studio head Barney Balaban had screened Vertigo (with the Big Reveal intact) to a few film critics in New York, who praised it as Alfred Hitchcock’s best film. After the scene was removed, Balaban had screened it again for a few journalists, but this time the result was altogether different: Those critics told Balaban that what they had just seen was one of Hitchcock’s worst films. According to Auiler’s book, Balaban forced Hitchcock to put the revelation scene back into the movie, despite the expense involved.

Coleman’s remembrance of events here is problematic. From what he told Auiler, the prints minus the revelation was shipped to theaters, and upon Balaban’s edict of restoring the scene those prints had to be recalled. This version of the events would be plausible if prints were normally shipped days in advance of the film’s premiere, but that normally occurred a couple of days before the movie would open. In addition, the premiere date would have had to be changed and that event publicized, as the logistics of recalling prints from theaters, reinserting the scene (either into the existing reels or destroying those and creating new ones), and shipping the new, revised print would have taken some time to perform.

Coleman was just shy of age 90 when Dan Auiler interviewed him; chances are Coleman might not have accurately recollected these events. Auiler agrees with that assessment, but with no other survivors or reference material to refute the story Auiler went with Coleman’s version. Auiler now speculates that what was recalled wasn’t the reels from at the theaters, but the prints sent to the labs to create the reels. “My impression is that it was more likely they had just gone out to the distribution labs, and had not arrived yet,” Auiler says. “That is my personal impression.” [Restorer Robert Harris stated to me that “all prints were originally struck at Tech Burbank — probably 300 or so.”]

At the earlier screening where the decision was made to cut the scene, there was one key person missing — one who was influential when it came to Alfred Hitchcock’s films: his wife Alma. As his creative partner and advisor dating as far back as the silent era, Alma’s wisdom would prevail for any big decisions on his films throughout his career. It is likely that when the screening without the revelation scene occurred, Alma was in the hospital being treated for cervical cancer, as she was dealing with her illness during much of the filming and post-production.

Dan Auiler suspects that shortly after Alma left the hospital on April 25 she finally viewed the revelation-less print, and it may have been at the same, later screening where Balaban ordered the scene back in. “[Taylor] recalled though that Alma was the one who saved that particular scene and was responsible for getting it back in,” Auiler says. “As an editor and a story analyst, she knew probably what Hitch himself had believed. … Alma saw what had happened in that subsequent screening during that lag [before] distribution, she said ‘No, this was a huge mistake.'””

Balaban agreed with Alma, probably at that same screening where the critics clearly hated the cut version. (Auiler points out that this is all based on oral history vs. what really happened. For this event Coleman was present, and Taylor could relay only what he learned from others, so there was no way to corroborate the exact details of who said what at which screenings.) “It could have been [that] very same screening and it could be that at that screening that’s where Alma … would also have Balaban’s ear and say, ‘The reason [the critics] are saying it sucks is because you [Hitch] took out the one critical moment!’ [Laughs]”

By this time, Hitchcock made his decision anyway. “Every story, though, definitely says Alma was the deciding and impassioned voice that said, ‘This has got to stay in there, Hitch.’ And of course for Hitch there was no question at that point that it was going back in at considerable expense.” Regardless of how Alma made her feelings known, her opinion alone carried a great deal of weight. “In every oral history of Hitchcock’s,” Auiler says, “if there was ever a question Alma was the deciding factor.”

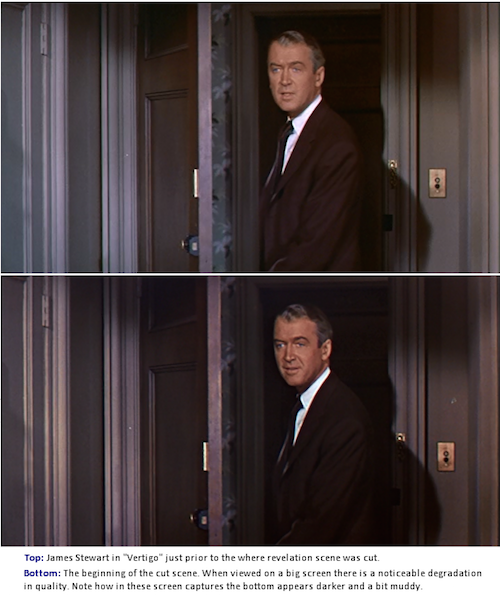

By reinserting the scene, the movie may have been saved from being relegated to one of Alfred Hitchcock’s less successful efforts. But the entire exercise ultimately came at a price, one that was evident during the restoration process for the version released in 1996. “According to Harris and Katz, if you look at the negative, one of the reasons that that particular scene survives in its degraded state in the redo is because it was cut out, [then] cut back in.” [In a conversation with restorer Robert Harris, conducted after this article was first published, Harris advised that the difference in quality was probably evident even at the time of the film’s original release, though maybe not as obvious.]

The difference in quality is apparent and even jarring when the cut scene first appears in the 1996 restored version. Leading to the edit in question, there’s a medium shot of Scottie telling Judy he’ll pick her up in half an hour; cut to close-up of Judy saying she’ll need more time; back to Scottie saying ”an hour”, followed by a shot of Judy saying, “Uh-huh.” Immediately after this, the cut to Scottie as he exits is where the quality of the film suddenly displays a high degree of graininess.

This aberration was most apparent in the 70mm theatrical restoration prints, where Harris and Katz’s attempt to improve it were limited by both technology and the budget. The transition appears to be only slightly improved in the DVD and Blu-ray releases. But ultimately we’re lucky to have the scene at all, beyond its being rightfully reinserted before its initial release. Until the dawning of the home video era — where deleted scenes were kept to add extra content to the media format in question — more often than not scenes left on the cutting room floor would be moved to the trash, never to be seen again. The Big Reveal in Vertigo may have come very close to not only being lost from the finished film, but also to being destroyed, never to be viewed.

When it was released, Vertigo proved to be contentious to movie goers and critics alike: why was the “mystery” resolved so early in the film? With the Big Reveal intact, Vertigo was neither a failure nor a success at the time of its release. (Dan Auiler confirmed that the film basically recouped its production costs, breaking even.) It received mixed reviews, its detractors making it clear they didn’t buy what they thought was a “Hitchcock and bull” storyline that had little basis in reality.

Expectations may have been high for something akin to more recent splashy and sparkling Hitchcock entertainments (e.g. Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, The Man Who Knew Too Much), in terms of popularity among audiences as well as box office receipts. When Vertigo failed to be a smash, one might wonder if Alfred Hitchcock thought he made the wrong decision in keeping the revelation scene. If that was the case, he never broached the subject publicly, always pointing to the concept of suspense (where the audience is given information unknown to the film’s characters) vs. surprise (where the audience and the characters learn information simultaneously), defending the scene as if its removal never happened.

Ironically Hitchcock had told the suspense/surprise difference to François Truffaut when the latter interviewed the Vertigo director for “Hitchcock by Truffaut” in August of 1962. In that book, the two directors discussed every film Alfred Hitchcock ever made. At the time, neither spoke the native language of the other and the entire interview was interpreted to both parties by a translator. When it came to Vertigo, Hitchcock could have told Truffaut what had happened with the revelation scene, but he didn’t — at least from what is heard on the audio that can be found at the Alfred Hitchcock Wiki (Part 21: The Wrong Man through “Vertigo”).

At one point, Hitchcock describes Judy’s emerging from her bathroom in her final transformation as Madeleine, and as Scottie is standing at the door waiting he gets an erection. (This was not in the book.) Hitchcock follows this by saying, “We will now tell a story, shut the machine off,” referring to the tape recorder (at 21:48). The nature of what Hitchcock said off the record is not known but, in all likelihood, it was not related to the revelation scene, considering the topic of the conversation that preceded the recorder being stopped.

Prior to this, Hitchcock told Truffaut how the original source material — “D’Entre Les Morts” by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac — didn’t include the concept of the revelation when the story shifted from Madeleine’s death to the entrance of Renée Sourange (the novel’s Judy Barton character; the secret that the two were the same person was revealed at the novel’s conclusion). As Hitchcock felt “nothing came next” (at 17:18 in the audio above) he states that “everybody was shocked when I said, ‘I’m going to spill the whole story now,’ soon after we started the second story [where Judy enters the film]. I’m going to tell all. They [the studio] said, ‘What, give the whole thing away now?’ I said, yes.”

(While off-topic, it should be noted that throughout “Hitchcock by Truffaut” the text differs greatly from the audio heard in the actual Hitchcock/Truffaut interviews; it appears that the dialog was paraphrased and condensed rather than being transcribed verbatim. The exchange above cannot be found in Truffaut’s book, and a similar passage within its text doesn’t appear to exist on the recording: “Everyone around me was against the change; they all felt that the revelation should be saved for the end of the picture.” More on this issue can be found in Lost in Translation? Listening to the Hitchcock Truffaut Interview by Janet Bergstrom. Regardless, Alfred Hitchcock never mentions that he agreed to cut the revelation scene.)

It’s outside of the scope of this article to deeply analyze why Vertigo may not have been as effective (and even confusing) without the scene in question. Many critics and film scholars have provided ample evidence as to its importance. But what may be the most perceptive examination about the scene and its placement in the film came from one who is widely recognized for his exploration of Hitchcock’s works: Robin Wood. While much has been written about Vertigo and the revelation, Wood’s analysis from Hitchcock’s Films (published in 1965) argues that by avoiding standard mystery conventions the film is a much richer experience. For the uninitiated, it is worth seeking out for Wood’s thought provoking analysis.

Wood is one of many who had made the case of how the film gains even more in depth with multiple viewings. This may be a key reason why the film wasn’t as heralded in 1958. At that time the movie-going experience was altogether different than in later decades. With rare exceptions (e.g., event films, like The Ten Commandments) films usually lasted only a week as part of a double feature then vanished entirely. Repertory theaters didn’t exist at this time, and videotapes were still a couple of decades away. People rarely went to a theater to see the same movie twice during that short viewing window. After it was gone, it wasn’t within reach to revisit. While it’s conceivable there were those who returned to the theater to see Vertigo again, they were in the minority. It was also a time when people tended to walk into the movie after it started, and stay for the next showing to see the beginning. In that sense, it was a bit of a dry run for Psycho, which was the first film that required theater staff to not let anyone in after it had begun.

On the other hand, this might be the best defense for not removing the revelation scene. With the era providing one opportunity to see the film before being quickly replaced the following week, the information presented at the start of the last act lets the audience consider the implications of what occurs from that point — among them how Elster remade Judy for monetary gain but Scottie repeats Judy’s transformation for more unsettling reasons; that Judy recognizes she is losing her identity a second time and reliving similar feelings during the first; that when Judy gives in to Scottie she has fully become Madeline to the point of wearing the same jewelry that finally cuts through to the entire deception. Knowing the truth is not only suspenseful; it makes the viewer anxious for the implications of a shattering climax. Without the scene, it is just a mystery— — something Alfred Hitchcock abhorred and always did his best to avoid.

As any savvy film buff knows, Vertigo was reevaluated years after its initial release and gradually gained in stature to where it has been accepted as one of the best motion pictures ever made, even toppling Citizen Kane from its position of No. 1 in the BAFTA poll held once each decade. But it can be argued that without the Big Reveal, Vertigo might not have been regarded as being anything near “great.” Despite the acting and the production values, there was no getting around the fact that what followed the missing scene was written with that sequence in the audience’s mind. Without it, the motivations and proceedings appear muddled. Judy’s actions don’t seem to make sense if the audience accepts her as a totally different person — which would have been the likely scenario without the revelation scene.

Does Dan Auiler agree with this opinion? “Absolutely. There’s no question about it, for me. … I think it works with audiences to have it where it’s at, period. I think that having the reveal too close to the end would have it wash with all the action at the end, and there would be all these questions about working it out. … It would be too confusing. I think also because of what has happened in post-modern cinema writing criticism that moment makes it where it’s another mystery suspense film that is a different item that Hitchcock accidentally stumbled onto a kind of manipulation in the story that was by all accounts a sort of a mistake in a funny way but makes it modern, makes it so intensely modern that it can actually beat a film like ‘Citizen Kane’ which is an extraordinary film. I sometimes scratch my head and say, ‘Really!? Really!?’ [Laughs]”

“But I can see from a modern point of view why ‘Vertigo’ is in many ways a better example of cinema than the sometimes limited, really, theatrically traditional film of ‘Citizen Kane,'” Auiler says. “They’re both brilliant and really they share a spot in the heart; there really is no difference between the two as far as impact on me as a person. … There are some films that get under your skin; it doesn’t matter how bad or good they are.”

Without the revelation scene Auiler – along with countless numbers of that film’s devotees — might not have been as profoundly impacted. What may never be answered is what drove Alfred Hitchcock to make a decision that one would assume had gone against his artistic sensibilities. As mentioned here, there were many factors that may have caused Hitchcock to have been extremely stressed, the largest one being Alma’s illness. Perhaps Hitchcock knew that once Alma had seen the film the right decision would be made, though from the timeline her weighing in was cut extremely close.

Regardless, this is one movie where the plot’s Big Reveal was eclipsed by one from within the production itself — and one that might have been forgotten altogether if not for Dan Auiler’s simple desire to write a book examining a film he very much loved.

Special thanks to Dan Auiler.

©2015 Mike Tiano. All Rights Reserved.

- Remembering Billy James: ‘He Was One of the Good Ones’ - May 15, 2025

- ‘Becoming Led Zeppelin’ (2025): Movie Review - March 11, 2025

- Grateful Dead’s Kennedy Center Honors: What Was Missed - January 27, 2025

It’s refreshing to read an article about an aspect of a great film that I was not aware of. I need to check this book out.

Thanks to the writer of the article and the researcher, this was an interesting read. Vertigo and the revelation scene are a school to movie directors. The movie Gone Girl took a lot of notes from Vertigo as told by the director in the film’s bluray commentary.