The sad and early death of Gene Clark couldn’t overshadow a remarkable stint as the Byrds’ principal songwriter in the mid-1960s. By the time he departed for a solo career, the Byrds had issued two firmament-shaking albums – and of those 23 songs, six were written by Bob Dylan while eight were written by Clark.

Along with featured vocalists Jim (later known to the world as Roger) McGuinn and David Crosby, bassist Chris Hillman and drummer Michael Clarke, Clark smashed onto the airwaves out of Los Angeles in 1965 with an electrified version of Bob Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man,” promptly scoring a No. 1 international hit. Coalescing folk with rock, the Rock and Roll Hall of Famers pioneered an entirely new category of music, aptly titled “folk rock.”

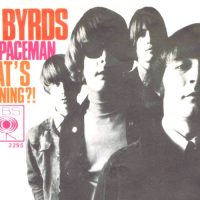

Illustrated with fluid harmonies and resonant 12-string guitars, the Byrds continued assaulting the charts in the 1960s with singles like “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better,” “All I Really Want To Do,” “Turn! Turn! Turn!,” “Eight Miles High,” “Mr. Spaceman,” “So You Want to be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star” and “My Back Pages.” As the band continued its travels, they fathered another new wave of music by fusing country arrangements with rock rhythms.

By then, of course, Gene Clark had already departed for a solo career. He’d end up with a discography boasting some 30 albums, counting his efforts with the Byrds, solo albums and collaborative post-Byrds recordings with the Gosdin Brothers, bluegrass star Doug Dilliard, former Byrds McGuinn and Hillman and the Textones’ Carla Olson, on what would be Clark’s final studio release, 1987’s So Rebellious a Lover.

We talked the following summer, as an animated Clark discussed adapting from one genre to another in a career that always made a winning combination of folk, country and rock ‘n’ roll, as well as the lasting impact of the Byrds, and his genre-melding creative process.

“All you have to do is have an understanding of the music,” he told me. “And these days, country and rock are a lot alike, and not so much different than they used to be. That sort of started in the 1970s, with the country-rock thing. No, it actually started in the 1960s, but didn’t catch on until the 1970s! So, you can take a country song today, and make it a rock hit, just by changing the rhythm structure – the actual rhythm of the track, the technique of the rhythm, and make it a little more driving.”

But rock, especially when performed live, still struck Clark as being a bit more challenging to embody: “It requires a little more creativity, but even country music is starting to require that now – because it’s becoming more and more sophisticated,” Clark said. “But with rock, you’ve got all these different styles that include reggae, calypso, African rhythms, and jazz. In order to come up with something fresh in rock these days, you really have to put your mind to it.”

Rather than limiting himself to constantly utilizing one concrete incarnation, Gene Clark said “I’ve always liked playing with a variety of musicians, because it definitely broadens your horizons, and gives you more scope and inspiration.” That played out across a series of concerts and projects that included Glen Campbell, Leon Russell, Clarence White (himself a latter-day Byrd), Leland Sklar, John Hartford and Jeff Baxter.

Out of all of his recordings, Clark cited his 1974 solo project No Other – the saying that would eventually adorn Clark’s simple headstone in his hometown of Tipton, Missouri – as being one personal favorite, saying that it held up as a good piece of poetry and music. He also favored the initial two Byrds longplayers, Mr. Tambourine Man and Turn! Turn! Turn, both from 1965. Of the two, Clark said he prefers the former, comparing Turn! Turn! Turn! to the Byrds’ 1973 self-titled reunion disc – which was also hastily prepared.

“I think I like the first one better, because we took a long time in really formulating the material, and getting it all together,” Clark said. “We worked really hard on that record, and I think it’s more exact and together than the second album, because with that one, we were rushed into getting it out quickly, and just didn’t have a lot of time to sort the material out.”

Nearly 25 years into his career, Gene Clark wasn’t really partial to either the studio or the stage, saying each carried its own inescapable pluses and minuses.

“Sometimes the studio can be a lot more pleasant than playing live,” he said. “It always depends on the project. If you’ve got a lot of strong new material, a fresh approach and really good musicians, then the studio is great. And if you’re doing a concert tour where you’re playing with people you really like, you’re playing good venues and there’ a lot of good press, then that’s great, too!”

Clark described a creative process that included writing material on both acoustic and electric guitar. “When I know I’m going to be doing a project, I spend a few weeks before doing it, actually writing more songs,” Clark said. “Then I go over them all with the producer, and we’ll pick out the ones that we feel are the strongest, and we’ll always pick out more than we need. Then we’ll record 13 or 14 songs, but if the first 10 come out perfect, we’ll just use those – because we know we have an album right there.”

Certainly one of the most innovative bands of the 1960s, the Byrds not only spurred major contemporaries like Bob Dylan (who, after witnessing and being a party to their success, assumed an electric format) and the Beatles (whose Rubber Soul was streaked with folk-rock aspirations) into adopting their distinctive sound and style. But even as we spoke in the synthesizer-laden 1980s, scads of young musicians still regarded them as a prime inspiration.

“The Byrds are bigger now than they ever were,” Gene Clark told me in 1988, though the words ring true even today. “They were and still are a tremendous, gigantic influence. I heard from all over the place, and read interviews with people who say the Byrds are their favorite group, or the Byrds and the Beatles.”

Perhaps sensing the growing popularity of acoustic bands like R.E.M., which was then on the verge of major-label success, not to mention the looming vogue of “unplugged” concerts on MTV, Clark said he felt that radio was becoming more receptive and liberal: “It started getting tight about 10 years ago, and even up to about five years ago, it was really right. But the market is a lot more open now, whether it’s folk, folk-rock or country-rock – and, as long as it’s good, it has a chance.”

In the beginning, Gene Clark was the Byrds’ key songwriter, having penned a good portion of the music on Mr. Tambourine Man, Turn! Turn! Turn and Preflyte, an album of pre-1964 demos that didn’t see the light of day until 1969. Besides “I’ll Feel A Whole Lot Better” – which has been covered by a diverse assortment of artists from Johnny Rivers and the Flamin’ Groovies to the Three O’Clock and Tom Petty – another song that’s been dragged through the cover mill is “Eight Miles High.” The original take of that 1966 hit was then newly available on a collection of outtakes and demos called Never Before, which also included unreleased vintage Byrds items like the Clark-penned title cut, an early rendition of Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” and “It Happens Every Day,” among others. Clark said there was also a wealth of material when the Byrds recorded.

“Everybody in the group was writing a lot in those days, so we had an awful lot of stuff,” Clark said. “We were always recording too, but when it came time to do an album, a certain amount of material was always equally divided among us – and so a lot of our songs were just never recorded.”

Clark had particularly sharp memories of the creation of “Eight Miles High,” an esoteric number initially recorded late in 1965. Reflecting on how the Byrds were absorbing jazz at the time, listening to a lot of John Coltrane, Clark views the tune as being the first jazz-rock/psychedelic recording: “I was on the road when I started writing the poetry for that, and didn’t quite finish, so Crosby helped me finish,” Gene Clark said. “McGuinn was mainly responsible for the arrangement, and I wrote the melody. We really put a lot of time into that song, and were trying to do something unique. We wanted to move into a new area.”

- Why Aerosmith Finally Broke Through With ‘Get Your Wings’ - March 5, 2024

- How ‘The Birds, the Bees and the Monkees’ Blew Away Their Pre-Fab Image - April 10, 2023

- Steve Howe Made a Colorful, Quite Surprising Debut With Tomorrow - February 20, 2023