More than four decades later, Paul McCartney’s Band on the Run still represents the creative highpoint of his career away from the Beatles. No other solo recording so completely underscores the difficult freedom quest he had to undertake, and none is more personal.

The album’s unifying theme of escape is more subtle (and thus more commercial) than the blunt confessional style of his former partner John Lennon. McCartney, instead, uses broader storytelling brushstrokes — skillfully weaving his own desire to break away from the Beatles with the age-old myths of ne’er-do-wells, hitchhikers and outsiders.

Much of the backstory, of course, is familiar. Band on the Run, released on December 5, 1973, memorably begins with this crashing jailbreak of a title tune, establishing a rousing narrative; includes a pair of fervent rock songs about traveling fast (the zooming, Beatlesque “Jet”; and the raucous “Helen Wheels”); explores rebirth through adversity (“Mrs. Vandebilt,” which perhaps best incorporates their surroundings at EMI’s studio in Lagos, Nigeria; and “Mamunia”); and then moves, inevitably, into the final passage we all take (“Picasso’s Last Words”).

The anthematic “Nineteen Hundred and Eighty Five” seems to be building toward a sweeping finale, and some sense of closure, only to abruptly reprise the title track — closing the circle for a wanderer who may occasionally long for the settled life, but can never quite commit to sticking with one thing. Deeper inspection finds that even “Bluebird,” a friendly aside in the familiar Paul McCartney ballad style, ends up longing for another place — as McCartney’s character imagines taking wing himself, where “at last we will be free.” There is a restlessness, a sense of destiny unfulfilled.

It pushes Paul McCartney to new places, as he incorporates every part of his pop genius here — handling most of the instrumentation (even the drums, after a sideman bolted), nearly all of the songwriting and singing (the underrated Denny Laine makes a key contribution on “No Words”) and brilliantly employing his own varied musical idiosyncracies. No Paul McCartney effort yet has taken so many chances, nor so successfully blended his interests in the melodic, the orchestral, the rocking and the episodic.

In keeping, of the Beatles solo recordings, Band on the Run always sounded the most to me like something the old band might have put together. There’s the Lennon knockoff “Let Me Roll It,” of course, and an introductory guitar signature on “Mamunia” that recalls George Harrison’s “Give Me Love.” The opening title song would have fit in nicely on side two of Abbey Road. In fact, George himself had uttered a key phrase on that mini-rock opera: “If we ever get out of here,” during an interminable business meeting around the same time.

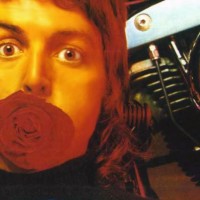

Yet, experiencing Band on the Run some 40 years on, I notice deeper, more emotional connections: The album’s famous cover image suggests a dark aftermath for the glittering 1960s of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper, something that was so utterly true. The impish complexity of “Picasso’s Last Words” — they form a chorus of “drink to me, drink to my health, you know I can’t drink any more” — seems to deftly mourn the thrilling experimentation of that period, as well.

The lyric itself for “Picasso’s Last Words” was suggested as a songwriting dare by the actor Dustin Hoffman, who was filming in Africa, and from there Paul McCartney decided to adopt a format in keeping with the angular style of his painter subject — tossing in found objects like previous songs (both “Jet” and “Mrs. Vandebilt”) and a polyrhythm on shaker courtesy of studio guest Ginger Baker from Cream. I suddenly discovered, all over again, a sense of creative danger lifting this record.

That’s something I hadn’t heard before in solo work by McCartney — a distractable genius who so often, then as now, chose to stay close to home, to play it safe. He was, and this was so important to the enduring success of Band on the Run, unsure of where he was going but willing to strike out anyway — willing, I realize all at once, to fail. That led to Paul McCartney’s greatest success of all.

- How Deep Cuts on ‘Music From Big Pink’ Underscore the Band’s Triumph - July 31, 2023

- How ‘Islands’ Signaled the Sad End of the Band’s Five-Man Edition - March 15, 2022

- The Band’s ‘Christmas Must Be Tonight’ Remains an Unjustly Overlooked Holiday Classic - December 25, 2016