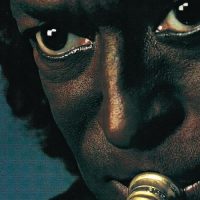

Sorcerer stood as the clearest sign yet that Miles Davis was letting go of the wheel. The project, released in December 1967, illustrated a new willingness to experiment, something that girded listeners for the coming journey between the more traditional approach Davis was then rapidly abandoning and an aggressive ingenuity which would soon become closely associated with this, his second great group.

By ’67, all of the names so familiar from the early Miles myth had moved on: John Coltrane, Bill Evans and Cannonball Adderley were each leading their own outfits. Replacing them were less overtly sympathetic, far-more challenging innovators, with tenor man Wayne Shorter and pianist Herbie Hancock making the most stirring early impressions.

Together, they would push the group’s sound into electric instrumentation, establishing frankly audacious rhythms — and, finally, help create a jazz-purist maelstrom, even as Miles Davis sometimes seemed to take a backseat. Sorcerer, though, still deftly combines touches of a familiar acoustic sound that Davis had established over the late 1950s and early ’60s as the paradigm, even while adding the free-range inventiveness that characterized Miles’ explorations to come.

Were there times when it seemed like he might veer into a musical ditch? Sure. After all, by 1972, Miles Davis was playing his trumpet, no kidding, through a wah-wah pedal. His sound was as dissonant and willfully obtuse as it was funky and new. Still later, he moved into pop stylings, and finally into the then-new hip-hop sound.

Thrill, then, to the last moments of the Old Miles — here on Sorcerer, and on the immediate follow ups Nefertiti and Miles in the Sky from a year later. He’d rarely get as close to the middle of the jazz road again, even as he sets the clutch for what comes next on flinty meldings like “Prince of Darkness” and “Masqualero.”

“Prince of Darkness,” a Wayne Shorter tune that came to define Miles Davis’ prickly persona, flirts with the Coltrane approach. By the end of the tune, though, Shorter has gotten his feet planted — and sounds like his very own man. “Masqualero,” meanwhile, features turbulent, Med-Sea curves. It’s something that comes off as exciting and new, even while recalling the pleasant feel of Gil Evans orchestral work on Sketches of Spain.

A sign of his growing trust in where this group would go, and in this inventive new direction: Not a single tune on Sorcerer was written by Miles Davis.

- How Deep Cuts on ‘Music From Big Pink’ Underscore the Band’s Triumph - July 31, 2023

- How ‘Islands’ Signaled the Sad End of the Band’s Five-Man Edition - March 15, 2022

- The Band’s ‘Christmas Must Be Tonight’ Remains an Unjustly Overlooked Holiday Classic - December 25, 2016