Editor’s note: This column ran as part of an obituary package on the national Gannett News Service wire upon Dizzy Gillespie’s passing in 1993.

People told him those bullfrog cheeks would ruin his playing. The embouchure, very important.

Flinty, yet funny, John Birks Gillespie was insightful enough to understand that this would be his hook. Over the next five decades, Dizzy would establish himself as the penultimate of his kind, behind only Louis Armstrong as an ambassador for the music.

Like Satchmo, too, Gillespie was a revelatory trumpet player, but perhaps an even greater personality. He sold jazz, was for a time its very face. And now, like Armstrong, he seems lost to caricature. The cheeks; always, the cheeks.

I come back to Gillespie’s 75th birthday jubilee tour 15 years ago, as a wake of young would-bes (the then-largely unknown Claudio Roditi, Jon Faddis and Wallace Roney) joined him on stage. That tour, Gillespie’s last, was occasionally ragged, and maybe even disappointing if you were used to the reliable brilliance of his “Night In Tunisia” from another day.

This was history, though. We got a last, lingering look at Dizzy as the statesman genius, and mighty muse. Even old cats like Red Rodney and Doc Cheatham (since passed, too) took part.

That tour said: Enough with the cheeks, already.

Cheatham had met Gillespie when they were both playing in Cab Calloway’s band, But Dizzy had a falling out with Cab in 1941. Calloway with 10 stitches in his backside, that’s how that one ended.

Hard to believe of the ditzy Dizzy we later came to see in concert posters and album covers. He was serious about the music, even if we never knew.

Gillespie figured he was on to something new, something beyond the simple showband sounds of the day. Something that would be called the death of jazz, the death of music: Something he named, bebop.

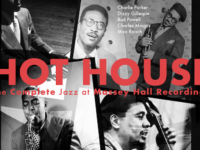

Things got going when he met saxophonist Charlie Parker, then just a guy from Kansas City with a horn, while on tour with Calloway. It wasn’t until 1945 that they got something down on vinyl. The most celebrated versions of forgotten classics like “Salt Peanuts” and “Groovin’ High” were born.

Gillespie and Parker stutter-stepped and left-turned. They took the standards and they sliced, diced and julienned them. In so doing, Parker became Gillespie’s countermelody. And in more ways than one.

Oo-papa-da, he might scat. “He beeped, when he should have bopped,” like that.

Dizzy was not, even in his serious pursuit of this newfound sound, the troubled jazzman. Not the heroin-adled player, crying in song. John Birks was fizzy, at once fierce and puppy-dog playful.

Like Miles Davis, many of his former bandmates became very famous. (That went on until the last, when Gillespie’s final bands produced Paquito D’Rivera and Arturo Sandoval.) And, also like Davis, he couldn’t have simply settled with his first innovation.

Gillespie’s fascination with rhythm would not only lead him to midwife bop, but then to co-parent the Afro-Cuban jazz movement in this country.

For roughly two decades from the mid-1940s, Gillespie’s output ranks among the most interesting in all of American music: It’s seering, unwieldy, deeply moving, slack-jaw groovy. Sometimes all in one stanza.

Yet we hear far more about Parker, whose myth was made through both his feiry intellect but also his quick demise. Dizzy survived, with a life-long wife, a consistent career that survived jazz’s evolution into rock then pop then jazz again, and a travelling salesman’s urge to circle the world with his trumpet.

Somehow his determination now counts against him. A constant presence, I suppose, is always a touch less intriguing than a startling flame out.

Gillespie’s emotional sweep, from beep to bop, from salsa-swing to rumba roll, made him a great musician. All the rest made him a great man.

He remains everything Parker wouldn’t — or couldn’t — let himself be: Very serious, yet very happy.

- How Deep Cuts on ‘Music From Big Pink’ Underscore the Band’s Triumph - July 31, 2023

- How ‘Islands’ Signaled the Sad End of the Band’s Five-Man Edition - March 15, 2022

- The Band’s ‘Christmas Must Be Tonight’ Remains an Unjustly Overlooked Holiday Classic - December 25, 2016