Jazz pianist Michael Wolff — an endlessly engaging player whom the New York Times has praised for “near impeccable good taste, technical facility and lyrical inventiveness” — joins us for a Something Else! Sitdown to discuss the lasting importance of his old boss Julian “Cannonball” Adderley, Nancy Wilson’s way with a song, the world’s weird attaction of Elvis Presley — oh, and what it’s like being Dear Old Dad around the Naked Brothers Band …

Nick DeRiso: You received some well-deserved rave reviews for 2009’s Joe’s Strut, a record that had a strong connection with your New Orleans roots. What’s next for you?

Michael Wolff: Oh, yeah, I was thinking about Professor Longhair, James Booker, all of the stuff from when I was young. I loved the way they played, loved that style — all that filigree. Fats Domino, too; such a soulful guy. To me, jazz has three kinds of moods — funky like that, a ballady kind of mood and a swinging mood. My goal now is make three specific CDs with those moods. The next one will be a funky one, maybe not super long. But I really want to have a similar mood throughout the whole thing. That could be something fun to approach.

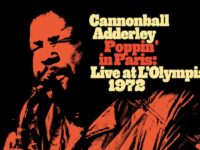

DeRiso: The title track reminded me of Joe Zawinul and, going further back, your first record with Adderley. Phenix, done just before Cannonball passed, featured a series of new interpretations of Adderley’s most famous tunes, from “Country Preacher” and “74 Miles Away” to “Walk Tall” and “Mercy Mercy Mercy.” That must have been intimidating, in a way, since Zawinul had made such a big imprint on the originals.

Wolff: It really wasn’t. I was so young that I wasn’t intimidated. I grew up listening to that, and I just thought that was my rightful place. I knew all of that music, so for me to get together with Cannonball, it felt so natural. It was so hard for me when Cannonball died, though. The next record was going to be all of my compositions. That was the perfect gig for me.

[ONE TRACK MIND: Jazz pianist Michael Wolff talks about key moments with Julian “Cannonball” Adderley, Warren Zevon, Charlie Hunter, Joe Zawinul and his band Impure Thoughts.]

DeRiso: Later, you worked for a number of years as musical director with the singer Nancy Wilson, another of Cannonball’s discoveries. How did you adapt your craft when working with a song stylist like Wilson?

Wolff: Every piano player, for better or worse, ends up playing with a bunch of singers. That’s your lot in life. I had accompanied Flora Purim. When I was with Cannonball, singers would sit in — Sarah Vaughan, things like that. With Nancy, she is such a great artist that it took me a couple of years to figure out what was best for her. It was a five-year experience, and I learned to think about what I wanted to be as an accompanist. I viewed her as a trumpet or sax, with the words she was singing as tones, and I would play off that. When I am accompanying any instrument, I want to make them sound as good as they can. We did some jazz songs; we did some funky stuff. In those days, in the 1970s, there was quite a mix of music. I learned how to conduct. I wrote for her, arranged — that was the most interesting thing, almost like a puzzle. It had to work for a jazz trio, for a trio with horns, or big band and orchestra. It was a really cool puzzle to figure out, great on-the-job training.

DeRiso: Set the scene for a young pianist, appearing with the legendary vibist Cal Tjader at the Concerts by the Sea at Redondo Beach in the early 1970s.

Wolff: I wasn’t old enough to even be in the club. The interesting thing was, in between sets I had to stay 10 feet away from the bar. I was reading a book and the rest of the band was out hitting on chicks. It was a great experience. His audience was totally mixed. We played tons of colleges, so there were kids in the audience who were my age. We played Latin dances, too. We played with Tito Puente’s band; our second gig was the Monterey Jazz Festival. Clark Terry was there, and Dizzy. It was a fantastic experience for a 20 year old. People always came and sat in with him. The audience was full of stars. Steve McQueen would come, and Marlon Brando. I loved that.

DeRiso: A new generation — like my 9 year old son — knows you through the work with your sons, the Naked Brothers Band — who’ve had a hit TV show, albums, tours. Was it a life-long dream to have them in the family business?

Wolff: What I wanted was to expose them to music, so that they would have that in their life. To think they would actually be musicians, I never thought of that. But it turned out that both of them are super talented at music and acting. I got to work with my family, an amazing experience. When we started, they were 6 and 9 — and my 9 year old had already written some amazing songs. I got to produce it with my wife, who was the director. I did the underscore, then I got to act with them. It started out that Nat would imitate me on the piano. It was a language they grew up around.

DeRiso: You lived for a time as a youngster in Memphis. Help me sort through the lasting allure of Elvis Presley.

Wolff: I was too young. All I knew was, my father was a physician for Elvis’ mother and his aunt. Elvis would come and pay in cash. But I dig Elvis. Musically, when I was kid, I remember people talking about it. But I’ve never been to Graceland. I was 9 when I left. And it wasn’t like 9 year olds now, where they are on the computer and know everything. I was just playing baseball and going to school. I didn’t know anything about the world.

DeRiso: On stage today, I still hear a lot of Cannonball Adderley in your banter. You seem to have internalized the way he interacted with the audience. Cannonball’s introductions to the music, sometimes, rival the compositions themselves for humor and individualism.

Wolff: He was so great at talking to people. Cannonball’s thing was that if you talked to the audience, you could connect with them musically. He’s the one who showed me you could talk with people from the bandstand. Now, that’s my personality; it comes out in me. Whatever is on my mind, I talk about. I always wonder if it’s going to take away from what we’re doing. I figure the people who are really good listeners will get something from it. When I go to a show, I want to see people’s real personality. I want to see a larger view of the work I am hearing. I dig it when somebody is funny or interesting.

DeRiso: Yet Adderley is so often overlooked, despite his contributions both as a band leader and on recordings like Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, one of jazz music’s most influential releases. Why is that?

Wolff: I always talk about that. I don’t know, of course. I would guess it’s possibly because he made it seem so inside and so easy that people didn’t realize how sophisticated he was. I remember when I joined the band, I called up Joe Zawinul on the phone. I knew how to accompany (cornetist) Nat (Adderley) when he played, but with Cannonball, I didn’t. Joe said: ‘If you figure it out, call me.’ Cannonball was so bluesy and so warm. It was palatable, and he had a lot of hits. Maybe it hid the fact of how great he was.

- Nick DeRiso’s Best of 2015 (Rock + Pop): Death Cab for Cutie, Joe Jackson, Toto + Others - January 18, 2016

- Nick DeRiso’s Best of 2015 (Blues, Jazz + R&B): Boz Scaggs, Gavin Harrison, Alabama Shakes - January 10, 2016

- Nick DeRiso’s Best of 2015 (Reissues + Live): John Oates, Led Zeppelin, Yes, Faces + others - January 7, 2016