In 1966, attorney Bernard Stollman founded the ESP-Disk label in New York City. Less than three years later, with orders dried up from established record labels bootlegging their better-selling records, the label was driven out of business.

This is a familiar story followed in some variation by thousands of start-up record labels over many years, but ESP-Disk has a special place in the history of avant garde music. During the first eighteen months of its existence, a staggering 45 records were recorded and released, virtually all of them recordings of some of the most controversial music in one of the most tumultuous times of American history.

The artists signed up to the label were ones not passed over by the “Bigs” because they lacked talent, but rather, they lacked commercial viability (although some records did beat the odds and charted). By willingly signing these progressively minded musicians, ESP eagerly took gambles that no other American record company dared to take.

This micro-label was the launching pad for many prestigious careers; the debut albums of Pharoah Sanders, Gato Barbieri, Sonny Simmons, Giuseppi Logan, Milford Graves and Henry Grimes had the ESP-Disk logos on them. Some more recognizable names such as Ornette Coleman, Sun Ra, Roswell Rudd, Sunny Murray and even Bob James have also recorded for ESP during those active, first few years. Most significantly, Albert Ayler recorded his most essential, groundbreaking records under ESP.

ESP welcomed underground acts from other genres, too. The Fugs, Pearls Before Swine and that quintessential whack-folk group, The Holy Modal Rounders, all found a home at Stollman’s enterprise.

After the then-legal bootlegging gutted the small company’s source of income, Stollman turned to licensing the catalog to European outfits for several decades. But now, ESP-Disk has returned. In 2005, a revived ESP-Disk began to reissue its own catalog. Today, the label is all the way back with brand new releases, too, including Totem>’s exciting Solar Forge CD.

It’s the maiden releases by Grimes, Logan and Graves that are of special interest here because just last month, ESP-Disk issued digitally remastered versions of these obscure but notable free jazz records on CD. Here’s a rundown of each of these almost-forgotten documents of mid-sixties avant garde:

Giuseppi Logan Quartet Giuseppi Logan Quartet

Giuseppi Logan Quartet Giuseppi Logan Quartet

Logan’s approach to whack jazz mirrored Ayler’s; most of his songs actually have discernible, almost child-like melodies that often appear to be launching pads for free-form improvision. Logan’s saxophone tone and technique is almost child-like as well, to the point that at the time he had been accused of not being able to play the instrument. Sometimes it does sound like a kid picking up the instrument for the first time and tooling around with it. Other times, though, he gives away the secret he seems to be trying to keep, that he really does have technique (albeit, not a whole lot of it).

Giuseppi Logan Quartet is really one of those records that’s more fascinating than truly good. It’s out there, and for a 1964 recording, it was right on the bleeding edge of the avant garde of that time. The opening “Tabla Suite” anticipated the Indian influence that would become integrated into Western music a few years later; the use of a tabla here is one of the earliest in jazz. Logan’s Pakistani oboe further helps to make the piece exotic.

Elsewhere, Logan sticks mainly with his alto and tenor saxes with varying results. More often than not, his band is outplaying him. Don Pullen, who would later become one of the best inside-outside piano players in jazz, does a decent Cecil Taylor impersonation when called upon in what is probably his recording debut. An early version Eddie Gomez is heard here, too, in much more unrestrained form than he was later heard in as Bill Evans’ longtime bassist. It’s Milford Graves, however, who puts in the best performance overall. Besides contributing that tabla, Graves rummages around his kit with controlled abandon, always propelling the other players. He proceeds to all but kill that kit on “Taneous.”

Logan didn’t record much at all after this challenging debut; a couple more ESP-Disk releases quickly recorded after this, a handful of sideman dates, and after 1966, nothing. By the early seventies he disappeared from public view altogether and is believed to have passed away in the early nineties. But no one seems to know for sure.

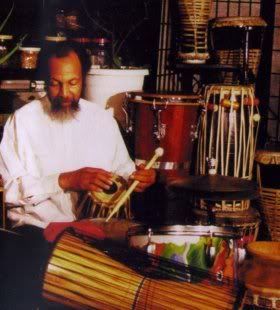

Milford Graves Percussion Ensemble

Milford Graves Percussion Ensemble

The same Milford Graves who starred on Giuseppi Logan’s Quartet album was the most recorded musician in ESP-Disk’s heyday, so perhaps it was inevitable that Stollman would ask Graves to record as a leader. Graves obliged, and brought along fellow percussionist Sunny Morgan for the recordings that become Milford Graves Percussion Ensemble.

An album completely lacking in tonal instruments would be difficult for most anyone to sit through, and I’m not going to pretend otherwise. Unlike the Logan record, though, the leader displays a lot of skill, here, as does his cohort Morgan. You can find African as well as South American influences in their rhythms and for students of drums and percussion, it might function well as a mini-clinic.

Everyone else will find little reason to listen it Percussion Ensemble more than once. As proficient as these demonstrations of drums, bells, gongs and shakers are, they’re still just demonstrations. There’s no other purpose listeners are going to be able to get out of this. It’s a somewhat interesting artifact that should lead you to seek Graves’ other recordings.

Henry Grimes Trio The Call

Henry Grimes Trio The Call

Last fall I covered the latest CD from whack jazz bass king William Parker and in passing was a shout out to a prior release of his where he is leading an unusual trio with drummer Walter Perkins and clarinetist Perry Robinson (Bob’s Pink Cadillac, 2002). But this is hardly the first time a bassist has led a record with this kind of getup. About 37 years earlier Robinson recorded in the same configuration led by another great avant garde jazz bass player of another generation: Henry Grimes.

Stollman wrote brief liner notes for many of these early releases and while he might not have had a flair for it that many writers

have, he could often be precise in his statements. That was certainly true when ended his brief comments in The Call with the sentence “A more accurate title for the album would be Henry Grimes/Perry Robinson.”

While Robinson’s supple clarinet is the focal point for much of these recordings, Grimes does get to strut his stuff on several occasions, as during his cello solo on “For Django” or the fleet-fingered bass solo at the beginning of “Saturday Night What Th’.” Mostly, though, he’s busy making up for the lack of chordal instrument in much of the same way Charlie Haden has done for Ornette Coleman. Actually, the six songs presented on this album—all written by either Grimes or Robinson—owe much to Coleman’s harmolodic concept of song construction, and they’re all good representations of the concept at that. They also has a strong element of swing that makes The Call a great listen even today.

Like Logan, Grimes dropped out of sight not long after he cut his first record. Happily, though, Grimes was located in 2002 and rejoined the whack jazz scene after about a 35 year period of working odd jobs and dropping out of music altogether. Remarkably, he has regained his chops and has even recorded a few more records (including a duet with free jazz drummer Rashied Ali that came out just this week, called Going to the Ritual).

Before Grimes could make his comeback, though, he needed a bass; he had long since sold his and he was destitute at the time he was found. Who stepped up and donated one to him?

William Parker.

- McCoy Tyner and Joe Henderson – ‘Forces of Nature: Live at Slugs’ (2024) - November 21, 2024

- Lydia Salnikova, “Christmas Means a Different Thing This Year” (2024): One Track Mind - November 19, 2024

- Darius Jones – ‘Legend of e’Boi (The Hypervigilant Eye)’ - November 15, 2024

Pingback: Owl Xounds Exploding Galaxy - 'The Coalescence' (2020) | Something Else!