My wife Cindy was at her computer looking at her Facebook news feed when she suddenly gasped. She tried to speak but couldn’t get the words out. I was sitting on the couch nearby and got up to look at her computer screen to see what the fuss was about: Perhaps she couldn’t believe some startling good news she read?

It was indeed startling, but unfortunately it wasn’t good news at all. When I saw the reason for her astonishment, I suddenly understood her reaction and I became equally shocked: Rush drummer Neil Peart had died from brain cancer.

It’s a journalistic rule to distinguish an individual so the reader is informed about said person. In this case, identifying Neil in the previous paragraph is almost superfluous: I doubt anyone reading this article didn’t recognize the name of the legendary musician who was a member of one of the most beloved rock bands that have ever existed. Using the word “beloved” isn’t hyperbole. Whenever I wear a Rush ball cap, it seems that numerous folks of all ages give me their thumbs up when they see it. It is as if we are all in the biggest secret fraternity that ever existed.

When Neil announced his retirement in 2016, no one except those closest to the band knew the true reasoning. It’s unknown if Neil Peart had been diagnosed with his illness while Rush was on what would be their final tour, but I can only speculate that chances are his illness was discovered afterward. It seems unlikely that Rush would have continued to tour once the diagnosis was made, but we really don’t know — and that’s OK. Fans may think they have a right to be told everything about their heroes, but my own motto in this day and age of inserting one’s self into others’ lives is mind your own fucking business.

There are many fans who have a personal connection with Rush to various degrees. In my case, I have a few. I had always hoped to have an opportunity to convey those to the band as it seemed we had a few major items in common — and beyond those, I would have liked to have personally thanked Neil for helping save one of my songs.

The first item was tied to events that occurred when I lived in Toronto, Ontario (or as locals called it, T.O.) in my early 20s. In the summer of 1975, I travelled from the Los Angeles area to that Canadian city to visit a good friend. However, there was another major reason for that visit. As many who are reading this might already know, I was a huge Yes fan. Having attended shows for Yes’ Relayer tour in Southern California, I thought it a great idea to make that visit when Yes brought that tour to Maple Leaf Gardens in T.O.

Thanks to Yes, I was already interested in stage lighting; they were the first band I can recall having the lights synchronized with the music, and not just simply illuminating the stage. My friend was a drummer in a band, and he encouraged me to move there to be their LD (lighting director) and roadie. Having been discouraged by my job in Long Beach at that time (which I detailed in my very first Something Else! article), I decided to accept the offer and made the necessary arrangements to move to T.O. to start a new chapter in my life.

I knew it would be a drastic change. Having lived in the Los Angeles area for most of my life – where the weather didn’t vary wildly during the year – I would find my new home’s climate to be jarring. I wasn’t prepared for Toronto’s excruciatingly muggy summers and the extremely cold and snowy winters. On the other hand, it was somewhat welcome that I would be witnessing an actual change of seasons, and ultimately it didn’t deter me: Being a young adult, I was at an age where I was ready to embark on this adventure of following my dreams, and venturing into the unknown.

My friend’s band eventually failed at their attempts at offering Ontario audiences an interesting mishmash of various styles (Grateful Dead jams/Pink Floyd spaciness/Billy Cobham jazzy flights intersecting with dance tunes from the likes of the Average White Band and the Doobie Brothers). But that led me to one of many LD gigs in Toronto, this first being with Ken Tobias – who had big radio hits and was a star in Canada. Ken and his band were about to begin a tour across the country, with the first gig slated for Thunder Bay, Ontario.

I travelled there in the equipment truck with Ken’s two roadies. The vehicle had one of those new cassette players, and the first tape played was Aerosmith’s debut album. Being heavily into the Beatles and progressive rock, I didn’t care for what I heard and voiced that opinion to my fellow crew members. But I found the second tape they played was markedly more interesting: Rush’s 2112. At that time, I wasn’t enamored of Geddy Lee’s high-pitched singing, but I recall telling the roadies that I found Rush’s songs eminently more to my liking than I did Aerosmith.

Beyond that, what I had in common with Rush was that I was treading the same ground they had covered, including interacting with their former roadies. By that time, Rush had already graduated to arenas, but the bands I worked with played the same T.O. club circuit Rush had previously treaded. These were primarily on and near Yonge Street and included the Gasworks, the Colonial Tavern, and the Piccadilly Tube.

That was one connection with Rush. The next one was closer to being one degree of separation. One band I worked with was Lynx, who enticingly combined metal and progressive rock. There were three of us on their road crew, and although we all served that band by hauling and setting up equipment, we each had our main roles.

I, of course, was the LD. There was an individual who acted as tour manager, named Marty. The third person was the drum tech as well as the one degree of separation I mentioned: Lorne Wheaton.

Lorne was a wiry (at the time), no-nonsense character, but who could be caustically funny in his own right. His heavy Canadian accent could be fodder for how others parody those from the Great White North. But above all, he was a genuinely decent person, and fun to be with. We worked on many Lynx shows together, and knowing his work ethic I wasn’t surprised to learn many years later that he became Neil Peart’s drum tech. Unlike numerous roadies I encountered in my travels, for whom getting laid seemed to be their main focus, Lorne had his priorities straight: It was apparent that he was fully aware that his No. 1 job was attending to the needs of the band, and ensuring the equipment was properly maintained at all times.

There was another connection during that era that I could view as two degrees of separation. During the two years I lived in Toronto, I worked for Audience Audio, a sound and light company that was led by a gentleman named Bruce Duncan. Bruce was a sweet, stocky guy who was known to have a slight speech impediment, where his R’s would sometimes sound as W’s. I only mention that as it was a distinguishing characteristic to everyone who knew him, and is in no way a slight on someone for whom I have tremendous gratitude and respect: I have Bruce to thank for recognizing my talent as an LD and helping me get many gigs, including recommending me to Lynx.

Bruce and I got along extremely well, and he was always quick to compliment me on my lighting acumen. One show in T.O. always jumps to mind, when we were both working for Ken Tobias — Bruce was the sound engineer — where out of nowhere he leaned over to me and shouted over the music, “The lights look fucking great.”

Another notable lighting gig Bruce helped me get was with Downchild Blues Band, a truly legendary Canadian group still going strong today. I was fortunate to have been LD for Downchild during this time as a certain guest artist sat in with the band on more than one occasion: keyboardist Ian McLagan, who happened to be recording with the Rolling Stones in T.O.

Shortly after I left Canada to return to L.A. in 1977, I learned that Bruce was the tour manager for Max Webster, another huge Canadian band that was supporting Rush on the Farewell to Kings tour. (This was the two degrees I mentioned: Bruce to Webster to Rush.) Upon returning to L.A., I reunited with Cindy (who was then my girlfriend), and she and I met with Bruce at the Max Webster gig at the renowned Whiskey a Go Go in Hollywood. I recall between sets the three of us ventured to the parking lot to do a toke in Bruce’s vehicle. As we were doing so Geddy — who was also at the famous club that evening — and members of the band were getting into a van to possibly do the same thing, and Bruce shouted a greeting to him.

Bruce had secured comps to attend us, for what was my first Rush show, on October 7, 1977 at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. It was UFO and not Max Webster who opened for Rush at that venue. Our box seats were at the front, almost directly to the side of stage right, and when UFO performed the view was obscured and the sound was awful. During the break between acts, Bruce agreed and had us move to folding chairs next to where the sound and lighting boards were stationed. Needless to say, the new location was a vast improvement both sonically and visually – and thanks to Bruce, my first Rush experience was, in a word, awesome.

I reconnected with Bruce through Facebook some time ago, and I’ll always be grateful to him for his kindness and support as well as his good humor: I have to mention one of his funny creations that has stuck with me. Around the time that the Andrea True Connection had a hit with “More, More, More,” Bruce came up with his own take on that song, replacing the title with a popular brand of microphone: “Shure, Shure, Shure, how do you mic it, how do you mic it.”

The last connection consisted of items I had in common specifically with bassist Geddy Lee. Like Geddy, I too was the child of Holocaust survivors: My parents emigrated from Europe to North America after World War II, and I also found I shared Lee’s outlook on religion: We were both proud of our heritage, while eschewing the trappings of religious dogma.

That connection led to a revelation that occurred after I heard the story of how he abandoned his given name Gary in favor of Geddy, even going as far as legally changing it. A quote found in a February 2016 story from Classic Rock tells the tale:

“My parents were Polish Jews, survivors of the Holocaust. They met when they were 13 at a work camp and they were both in Auschwitz for a time. My mom had such a strong Jewish accent, which is how I ended up being known as Geddy instead of Gary, my real name. My friend and I would be playing on the street and my mother would be calling me in, saying, ‘Geddy, come in the house!’ My friend would say, ‘What is she calling you?’ I said, ‘What do you mean? She’s calling me by my name.’ … so a little later, when I turned 16, I legally changed my name to Geddy, because so many people were calling me that anyway.”

I learned about the origin of Geddy’s name well before that article but whenever that was, it hit home. My mom also had an accent, and for my older brother Jerry it always sounded like mom was saying “Jeddy.” When my siblings and I would quote her as if she were speaking to him, we would mimic her voice and pronunciation in the same way, e.g. “Jeddy, take out the trash.”

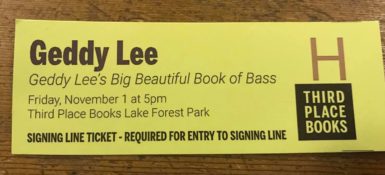

I did meet Geddy Lee, albeit fleetingly. In December 2018, he published “Geddy Lee’s Big Beautiful Book of Bass,” a large format coffee-table book where he exhaustively covered numerous vintage electric basses, and the many bass players who had inspired him. It was pricy when it was released, so I waited to purchase it. When I discovered that Lee was conducting a promotional tour of book stores – where one could purchase his book, have him personally autograph it, with his generously donating the proceeds to charity – I thought it best to wait to see if he made it to the Seattle area, where I lived.

That wait was a long one, but it paid off. Late in 2019, I learned Geddy would be making a stop at Third Place Books in the Lake Forest Park neighborhood of Seattle on November 1. One could only attend the event by purchasing the book in advance. As space would be limited, I immediately did so.

I also recognized that this might present a golden opportunity. I recently completed work on my debut album titled Creétisvan, which I’m informally calling my audio-biography as it features compositions written throughout my life. Geddy Lee’s appearance would be my big chance to give him a private URL to preview a handful of my tunes.

I created a very short, custom web address at tinyrul.com to make it easy for him to enter into a browser. As my handwriting could sometimes be illegible, I carefully wrote that URL on the back of one of my music business cards, ensuring its readability. While there was no guarantee Lee would take the card, let alone hear the tunes, I figured there was no harm in trying: At the very least, I would be able to meet him for the first time, while acquiring a signed copy of the book.

On the big day, Cindy and I arrived at the mall that lodged the store just a few minutes late and found that the signing event had already begun. There was a long line that wound its way through the mall to outside its back entrance; this was the line to obtain a ticket that assigned the book’s purchasers to a group. When one’s group letter was called, only then could one enter the bookstore area to line up for the actual signing. (The store itself was closed to the general public.) I believe each group numbered a few dozen.

Cindy and I ended up in group H, and when we got our ticket the store had just called group C. One might have thought that the huge crowd was there for an actual Rush performance. After we obtained our group ticket, we joined others in the seating area adjoining a small food court, which was packed with what seemed like hundreds of Rush fans.

When their group letter was announced, folks could then line up to actually meet Geddy, winding their way around aisles of books to an area that was hidden from outside the store area. Lee couldn’t be seen until one got close to where he was stationed.

After what seemed like an interminably long time, my group was finally called. While waiting, I started to silently rehearse exactly what I wanted to say, incorporating an item related to his book that might entice him (as divulged below). I knew I had to be precise: There would be no time for small talk or room for error, as the staff’s goal was to remove the shrink wrap from the book in prep of its being autographed, let the attendees say a scant few words to Geddy, maybe get a selfie and fist bump, then quickly exit the area with their signed tome.

When I finally was face to face with Geddy Lee, I carefully (if anxiously) launched into my rehearsed rap.

“Hi, Geddy, my name is Mike Tiano, and this is my wife Cindy.” [Cindy was only interested in saying “Hi,” but I wanted to be sure she was acknowledged.]

“I’ve completed an album of my own music.” [OK, my setup was now in motion.]

“I worked for Yes for many years.” [This was true: though I was no longer directly associated with Yes, I had been their official web site manager for over a decade and wrote the liner notes for four of their Rhino remasters in 2003.]

“I knew Chris Squire …” [Yes’ legendary bass player was profoundly influential to Geddy and I knew he was included in the book. As Yes’ site manager I had interacted with Chris on countless occasions, so that statement to Geddy was also true.]

“… and he enjoyed my music.” [Again, true, as far as I knew: before his death Chris’ wife Scotty had told me he really relished the songs he heard, including “The Dark Ages” — that one was ironic, as will be revealed shortly.]

Holding out my prepared business card I concluded with the payoff: “I’d be honored if you would preview a few of my tracks.”

I braced myself should Geddy reject it, having in the back of my mind the lyrics to Rush’s “Limelight”: “I can’t pretend a stranger is a long-awaited friend.” Even if this situation didn’t exactly mirror the one described in those lyrics, it still might have been too much to ask.

Regardless, I had come this far and still hoped for the best. Time stood still as Lee looked at the card in my hand for what seemed like ages, when in actuality it was only for a second.

“Sure,” he said, taking the card from me and shoving it into the front pocket of his jeans.

Relieved but excited, I thanked him, got a fist bump along with a hastily taken (resulting in a crappy) selfie, and Cindy and I exited the line with the autographed book. I was exhilarated that I accomplished my mission.

Subsequently, I never heard from Geddy Lee and have no idea if he listened to any of the tracks. I imagined that he did and was so impressed he raved to Neil Peart and Rush guitarist Alex Lifeson, “You have to check out this guy’s fantastic music!” Now knowing that at the time of the event Geddy was in all likelihood mentally preparing for Neil’s demise, I have put that particular fantasy out of my mind completely.

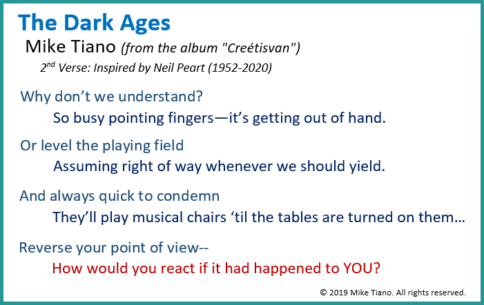

Beyond the connections I mentioned here, I wish I could have thanked Neil Peart for being influential to me through the effectiveness of his lyrical content. One example was for the very first song I recorded and mentioned earlier, titled “The Dark Ages.” The song’s concept was how some day deep into the future, folks in a hopefully more enlightened society will be shocked at the way humans currently treat each other. Another aspect was the notion that if one has not been faced with a critical decision then that person has no right to tell others how to behave.

When I first conceived the song, I pretty much wrote the first and third verses right away. But for the longest time, “The Dark Ages” remained unfinished because I could never come up with a satisfactory second verse. Then, not long before I recorded it, I started thinking about Neil’s lyrics in Rush, and his effective mastery at wordplay; one prime example was how “hold your fire,” a phrase commonly known for halting gunfire, would unexpectedly be repurposed (“…keep it burning bright”).

Inspired by Neil’s adeptness at turning a phrase, the second verse for “The Dark Ages” came to me in a flash: There was little effort in its creation. I am particularly proud of how Neil’s inspiration resulted in phrases that incorporated chairs/tables and fingers/hand in different manners. I present the complete verse here to demonstrate how Neil Peart inspired me both in tribute to his enormous talents and as a way of paying my respects to his passing.

Peart’s death moved me to revisit my connection to Rush, and I know I’m not alone. I recently learned that keyboardist Jonathan Sindelman, a good friend and contributor to my forthcoming album (as well as a fellow major Rush fan), had a comparable reaction to the news of Neil’s demise. Over a year ago, Jonathan and some kindred spirits participated in a Rush-motivated project and titled themselves A Farewell to Kings, and after Neil’s death they decided to go public with it. Check out the video for their song “Huck Finn” below (and learn more about them here).

In a way, it was Neil Peart who provided the fuel that catapulted Rush to creative heights, and maybe even their stardom. Before he took over the role of drummer from John Rutsey, the group might have been destined for the scrap heap of countless bands that offered blues-based tunes containing heavy metal-ish riffs and “hey baby, let’s screw” lyrics.

Instead, Neil’s lyrics were contemplative, articulate, and imaginative. They touched on personal, philosophical, and allegorical concepts to the enchantment of fans of all ages, and to cultures far and wide. (In addition, Neil Peart demonstrated that his writing talent wasn’t limited to songs: Beyond the lyrics he provided to Rush, he authored many books covering a vast range of subjects.)

Neil may have also been instrumental in shaping Rush’s musical direction. Before joining the band, he lived in England in the early 1970s, and his exposure to the then-burgeoning prog music scene might have later inspired Geddy and Alex to create more inventive compositions as well as increased their technical proficiency as musicians.

(Side note: I was disappointed that the popular documentary Beyond the Lighted Stage barely acknowledged the enormous impact that progressive rock had on Rush. While that film adequately documents the band’s general history, I would point anyone who wants to understand the evolution of their music to Rush: The Rise of Kings, which includes pertinent deep dives into how prog was key to their development.)

Early in their career, Rush faced what appeared to be insurmountable odds. As one attempting to ensure my first album of inventive rock doesn’t get lost in the void of countless releases, I am heartened by their example of being true to themselves, by not playing it safe. The path they took benefitted them both as individuals and as a band, and gave us all many albums filled with original, timeless, and memorable music.

Recently, I came across an article (linked from the Rush Forum) where a fan ran into Neil Peart during one of the drummer’s motorcycle adventures. After surreptitiously joining Neil for lunch, the two were preparing to get on their bikes to go their separate ways, and upon learning the fan would be heading in a different direction (in other words, not following him), Neil offered the following advice. “Never follow anyone. Be your own hero.”

Along with so many folks around the world, I mourn Neil’s passing. Peart was a talented human being who may have been private and guarded but appeared to be thoughtful, witty, intelligent, and above all, honest. His influence as a musician and composer is huge and will reverberate down through the ages.

Posthumously, Neil Peart has inspired me, yet again. This time with this introspective journey down memory lane, recalling special events and relationships in my life — including people, artists, and bands who are gone and those who are still with us today. Essentially, an evocation of the sentiments similar to those conveyed in the Beatles’ song “In My Life.”

Thank you, Neil, Alex, and Geddy for inspiring me to be my own hero.

© 2020 Mike Tiano. All Rights Reserved.

- 60 Years Later, the Beatles’ ‘Hard Day’s Night’ Is Still Revolutionary - August 20, 2024

- ‘Penny Singleton: A Biography’: ‘Blondie’ and Beyond - July 4, 2024

- The Beatles in Seattle 1964: Internet Archive - May 8, 2024