Stephen Stills is one of the few rock artists who can claim to have grabbed the elusive brass ring of critical and commercial success not just once or even twice, but three times.

The first time was as a group member of Buffalo Springfield and writer of their 1967 hit “For What It’s Worth,” taken from their acclaimed first record. After Buffalo Springfield folded, he formed one-third of supergroup Crosby Stills and Nash, whose definitive performance at Woodstock in 1969 helped rocket their self-titled debut album into multiplatinum orbit. And finally, just to make it perfectly clear he wasn’t simply riding the coat tails of others, in 1970 Stills released his first solo effort, which went to No. 3 on the album charts and spawned a Top 20 single, “Love the One You’re With.”

All milestones for sure, but these three classics have tended to obscure the rest of Stephen Stills’ work. And that’s unfortunate, because in Stills’ canon is an often overlooked gem in many ways the equal of his other projects: an album called Manassas, made by a band of the same name.

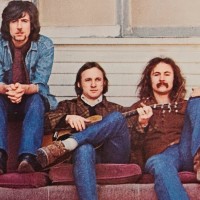

This seven-piece aggregation was assembled by combining players from Stills’ road band with others from the last incarnation of the Flying Burrito Brothers, which included ex-Byrds’ bassist Chris Hillman. So, though Stills was the acknowledged leader, officially Manassas has always correctly been referred to as a band — one with a “benevolent dictator” perhaps, but a band nonetheless.

The musicians’ wide range of experience enabled them to move between various forms of American popular music, integrating rock, pop, country, blues, Latin rhythms and other bits as well. This was very much in evidence on the group’s 1972 self-titled release, an album with so much good material that it came out as a two-record set. Even the names of the songs gave clues as to the variety found in the grooves: “Cuban Bluegrass,” “Colorado,” “The Love Gangster,” “Blues Man.”

One could hear the influences weaving in and out of the mix, courtesy of: Al Perkins’ pedal steel; Joe Lala’s percussion work; the tight-but-loose rhythm section of bassist Calvin Samuels and drummer Dallas Taylor; the stellar presence of keyboard ace Paul Harris; and the tenor harmony voice and rhythm guitar of Chris Hillman.

And let’s not forget Stephen Stills himself, writing and singing the songs, and playing his distinct lead guitar style, tying it all together. Even the first side is cut together as a seamless medley like production, with the other sides thematically arranged for maximum effect. Overall, think the Eagles meets Santana meets Johnny Winter, with bits of the Grateful Dead and Jimi Hendrix’s Band of Gypsies in places.

Still, you have to wonder why this went under so many people’s radar, especially with the gap left by the breakup of CSN (and Young) in 1970. There could be a number of reasons.

First, there might have been some confusion as to what this actually was: a third Stephen Stills album or something else? After all, even the cover sports Stills’ name large above the Manassas logo.

Second, it was released in April of 1972, and shortly thereafter the band went off to tour Europe. Some of the television appearances they made while over there show that when they got warmed up, they were as good as or better than most of their contemporaries. After returning to the U.S., Manassas had to make time to accommodate Chris Hillman’s commitment to prep for a Byrds’ reunion tour starting in October, which might have slowed their momentum.

Finally, although Manassas did make the Top 10 in the album charts that year, it contained no successful single. But the Crosby and Nash duo effort released around the same time contained a Top 40 single, “Immigration Man.” Perhaps more significantly, Neil Young’s 1972 best-selling chart topper Harvest featured the singles “Heart of Gold,” which went to No. 1 in the charts, and “Old Man,” which reached the Top 40.

One could argue that Manassas had the tightest group of musicians, but vocal harmonies and moody, introspective song writing were probably felt by the public to be more closely linked to the Crosby Stills Nash and Young sound.

Manassas would put out another album, affected by internal turmoil and discontent and much less well received by both the critics and the public.

Eventually, various outside factors, including Hillman starting the Souther-Hillman-Furay Band and Stills and his old sparring partners reuniting Crosby Stills Nash and Young for a major world tour in 1974, would cause Manassas to officially call it quits in late 1973.

At least they left behind one great album to document their short existence, and maybe one day Manassas will take its place alongside Stephen Stills’ other, more famous contributions to rock ‘n’ roll.

- How David Bowie’s ‘The Next Day’ Stripped Away All of the Artifice - March 15, 2023

- Why Deep Purple’s ‘Who Do We Think We Are?’ Deserves Another Listen - January 11, 2023

- In Defense of the Often-Overlooked Mott the Hoople - November 10, 2022