by Nick DeRiso

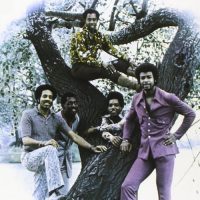

The doo-wopping Temptations – five guys that had both a way with harmony and these pillow-soft on-stage moves – probably should have been an oldies act years ago.

After all, a song like “My Girl,” recorded in 1964, might have held little resonance by the end of that same decade for a generation taking to the streets in throaty protest.

By then, however, the Temptations had evolved into a funky choir, one not afraid of taking even a psychedelic side road.

That made this one of the most scintillating of Motown bands. Moreover, in evolving, and fully grasping, that shift in paradigm, the Temps became the perhaps most important black vocal group ever.

They were just as relevant before Martin Luther King emerged as a Civil Rights pioneer as they were afterward – a nearly unheard-of 1960s transformation that matched headline-grabbing pop bands like the Beatles.

That they carry on today as, yes, an oldies act, drained of that sharp-edged rebellion and missing several familiar faces, can’t diminish their nearly decade-long period of brilliance.

Texarkana, Texas-native Otis Williams remains as the only surviving member of the original group. He and Melvin Franklin formed the nucleus of an ever-changing lineup that seemed to shed its skin with both timeliness and rare abandon.

In the halcyon early 1960s, falsetto Eddie Kendrick was the very picture of sweet naivety. He scored with hits like 1964’s “The Way You Do The Things You Do” (the Temptations’ first Top 20 hit) and 1966’s “Get Ready.”

The creator of many of that period’s vocal arrangements, as well as the guy who picked out the suits, Kendrick — or “Cornbread,” after a favorite delicacy – was the face of the Temps.

For a while.

Motown songsmith Smokey Robinson wrote “My Girl,” which would become the Temps’ first No. 1 song, for David Ruffin, once a backup singer. “Since I Lost My Baby,” which like “My Girl” was in the doo-wop vein, and the rollicking “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” (later famously covered by the Rolling Stones) followed with the Mississippi native out front.

That last song was more in keeping with this tenor’s nickname in the group, “Ruff.” He and new producer Norman Whitfield began to sharpen the Temptations’ edge, something that gives them street cred even today.

Still, a clash of egos meant Ruffin – despite his memorable raspy, gospel-style and fervent showmanship – would eventually become the first high-profile departure of this now sizzling 1960s hit machine.

He was replaced in 1968 by Dennis Edwards, a former member of Motown’s Contours (who had the memorable “Do You Love Me?”).

Like Kendrick, he was from Alabama. But there wasn’t much else they shared.

Edwards – who eventually sang lead on more hits than Ruffin and Kendricks combined – would take this band to the most surprising of places, helping to fashion with Whitfield some of the most important soul and funk recordings of the day.

They had all the modern elements: Congas, wah-wah pedals, and socially relevant commentary that likeable songs like “Angel Doll” never approached.

“Cloud 9” and “Papa Was A Rolling Stone,” both with Edwards singing lead, would win Grammy awards.

If they occasionally overreached (much of 1969’s “Puzzle People,” for instance, is hopelessly dated), the Temptations during this period were certainly the only doo-wop outfit trying to grasp such weighty issues. And brilliant moments of commentary like “Run Away Child, Running Wild” and “Ball of Confusion,” both Top 10 pop hits, were smartly interspersed with soul rockers like the No. 1 “I Can’t Get Next To You,” which harkened back to the old days by featuring each member at the mic.

Late into the 1970s, however, Edwards began an on-again, off-again relationship with Williams, who would eventually fire Edwards no less than three times. Edwards now tours seperately, with the Temptations Revue.

Kendrick, meanwhile, never liked the modern turn that defined the Temps’ sound with Whitfield as a producer. After a stirring 1971 chart-topper, the timeless “Just My Imagination” (also later done by the Stones), he was gone.

As was much of the magic from the Temps.

It had been some time since Kendrick, the doo-wop throwback, had held much sway – but in the end it seemed the Temptations were bound up in the way he did the things he did. (His solo career, oddly enough, would be defined by a disposable get-rich-quick hit in “Keep On Truckin,'” widely considered the first disco hit.)

While no one could deny the group’s innovative late-career forays, Kendrick it seemed was the underpinning that allowed for such experimentation.

The group continued to have minor hits into the 1980s, including “Treat Her Like a Lady.” But, as with the larger Motown sound, time drained away much of their relevance.

The Temptations’ 1989 induction in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame sparked talk of a reunion – and the group’s three most popular singers made plans for a tour, to be billed as “Ruffin/Kendrick/Edwards.”

But Kendrick was diagnosed with lung cancer and Ruffin died of a drug overdose in 1991. Kendrick had part of a lung removed, and continued to tour through the following year before succumbing. By 1986, Franklin had retired. He died of a brain seizure in 1995.

This group has subsequently lost that fizzy sense of being timely and cool. The Temptations are, in repose, finally that backward-looking act that they might have been destined to become if not for an ever-changing lineup that so thoroughly embraced its own moment.

There remains, though, this brilliant American legacy: The records. Few can get next to them.

- Nick DeRiso’s Best of 2015 (Rock + Pop): Death Cab for Cutie, Joe Jackson, Toto + Others - January 18, 2016

- Nick DeRiso’s Best of 2015 (Blues, Jazz + R&B): Boz Scaggs, Gavin Harrison, Alabama Shakes - January 10, 2016

- Nick DeRiso’s Best of 2015 (Reissues + Live): John Oates, Led Zeppelin, Yes, Faces + others - January 7, 2016