This is the first in a three-part series from Mick Raubenheimer examining Frank Zappa’s ‘Joe Garage,’ itself a three-part rock opera which arrived in September and November 1979. Joe’s Garage Act I became a Top 30 hit in the United States:

Chapter One: Forms New.

As model for Frank Zappa’s general musical aesthetic, as well as his more specific socio-ethical concerns, the 1979 concept album Joe’s Garage goes down a blast. It’s all here: The political concerns, the scatological scenery, the a/linear assault of various apparently unrelated imagery and sound patterns, the post-jazz pre-electronica staccato ambience, the eerily and oddly beautiful guitar solos, the eerie and the odd. And yes, the odd watermelon.

On the surface Joe’s Garage is just another crude vehicle for Zappa to release more of his vulgar music and overlong guitar indulgences. Look carefully, however, and you’ll notice that the LP has no surface; that is, in keeping with all his albums Joe’s Garage has no surface value as such.

In Frank Zappa’s world, every element is connected to every other element, forms an intrinsic cue to the over-arching tapestry and its enigmatic design, which he termed Conceptual Continuity: Zappa, then, exists only for the initiated, or rather, the “initiating” – for there is no consummate conclusion, no set point of pregnant apprehension of his dynamic catalog.

To follow Zappa on his delighted, madcap venture into unknowns, one must absorb his language, one must experience his attitude, his ontological mood. This is what we intend to extract from the album’s central sneer – this piece therefore attempts to unveil Frank Zappa’s aesthetic, his conceptual code.

The White Zone

Frank Zappa’s art can be pigeonholed. Yes it’s true. From a socio-ethical vantage, Zappa’s art is nothing more than a positivistic exercise against censorship. Ranging from the universal (ethical censorship) to the specific (aesthetic censorship), Zappa’s art is defined as an assertion of beauty and value behind conceptual iron curtains, and moreover, as the lewd idea that essential human beauty thrives exactly where various dust-smitten configurations of censorship forbid experience, sensation, and yes even presence.

Joe’s Garage serves as a prime model for the elucidation of both poles:

Ethically it protests (in trademark idiosyncratic complexity) the ever-looming atmosphere of socio-individual censorship – individual acts as virtuous only if they promote the dogma-hewn masses, ie. if they aren’t individualistic.

Aesthetically it sneeringly ignores musical/genre prescriptions and casually asserts Zappa’s musical language – a random and carefree collage of genre-affections boiled into a signature froth: Zappa’s aesthetic essentially concerned with, amongst others, the challenge of creating harmony between apparently irreconcilable patterns/sound-units. Music to infect the –

“White zone is for loading and unloading only … if you have to load, or unload, go to the white zone … you’ll love it, it’s a way of life.”

Chapter Two: The Stupid Story

Joe’s Garage is a silly story about how the Powers That Be convert society into a neat package made up of cute little units (“individuals”) moved around by cute little forces (the current needs of the mass body). Along the way, Zappa comments on many topics including art, sexual behavior, beauty, religion, Scientology (hilariously modified in the album as Appliantology, whose guru is L Ron Hoover), censorship, Big Brother, and the strands that interconnect them.

The basic satirical message is self-explanatory: The central character is a teen-next-door whose sole and innocent aim is self-expression, represented by his musical and romantic ambitions – art and sex being essentially expressions of individual Self.

His aspirations are common and modest, never develop beyond the teenage dreams of fronting a band and going steady, making Joe a representative of individual man (with stress on individuality: Unlike the common man, Joe never compromises his individual self by “getting a good job,” by falling in line with the –

“White zone is for loading and unloading only, if you have to load or unload, go to the white zone”

Invariably these innocent pursuits, and specifically their passionate insistence, become threatening to his monochromatic social superstructure, the pristine grey-scape home to the Central Scrutinizer (a robotic, semi-objective narrator/commentator) and the Law gets called in.

Joe gets shipped off to a correctional facility, where those most basic and effective techniques of correction are applied – violation of the independent / threatening self through violent removal of his individual freedom and expression, and complementary violent assertion of prescribed behavior.

Upon release, however, Joe finds he has transcended the Orwellian society’s ethical and aesthetic restrictions and succeeds in expressing his soul through the abstract language of instrumental music, able to create sublime beauty fed only by the monochrome melody of the –

“White zone is for loading and unloading only, if you want to load or unload go to …”

Joe’s transcendence, however, comes at a price: Having no society with which to interact, he retreats into an isolated madness. His expressions have value only for himself, are seemingly bereft of potency: Joe’s music is imaginary.

But not for Frank Zappa. For him, art could never be sterilized – and so, in a parallel universe, Joe ends up tweaking knobs in the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen (the name of Zappa’s legendary home-recording studio), releasing his idiosyncratic compositions into the minds of thousands who can but grin and bear the beauty of it all.

- How the Pixies Changed Everything With ‘Surfer Rosa’ - July 12, 2023

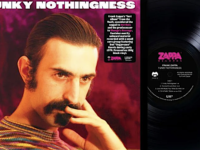

- Frank Zappa – ‘Funky Nothingness’ (2023) - June 30, 2023

- How Jim White’s ‘Wrong-Eyed Jesus!’ Changed My Mind About Country Music - June 14, 2023