The What-ing What Project? Never, perhaps, has a figure in rock music been simultaneously so famous and so … anonymous.

Alan Parsons, after all, worked as an engineer on Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon and Paul McCartney’s Red Rose Speedway; and was producer for the Hollies’ “The Air That I Breathe,” Pilot’s “Magic” and Al Stewart’s “Year of the Cat,” among others; was a hitmaker in his own right with tracks like “Eye in the Sky” and “Games People Play”; and, yeah, was the guy whose instrumental “Sirius” was the soundtrack to six pro basketball championships for the Michael Jordan-era Chicago Bulls.

Yet Parsons would probably get carded, anyway, if the long-bearded dude wasn’t old enough to be dean of the college of Caring for Magical Creatures. You could blame the behind-the-scenes ennui of studio work, or that his band — the blandly titled Alan Parsons Project — delved into the perhaps too-thoughtful intersections of rock music with literature, fantasy, robotics and psychology. Prog rock? Nerd rock was more like it.

Here are thoughts on five favorite moments, beginning with a recognizable radio favorite and then going much deeper into the Alan Parsons Project’s discography …

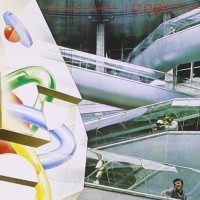

“I WOULDN’T WANT TO BE LIKE YOU,” (I ROBOT, 1977): A nasty little groove, with an even nastier put-down lyric, this is perhaps the definitive performance from the grooviest of the Alan Parsons Project’s typical lead-vocalists-by-committee, Lenny Zakatek.

He adds a funky grit that was often missing in prog-rock, both then and now — and it remains a world away from the spooky whisper that Eric Woolfson brought to later-period, far more well-known hits like “Time” and “Eye in the Sky.” No, Zakatek is all pissed-off venom, and the band matches that with perhaps its most dangerous-sounding intro: They start with an echoing electric keyboard, before adding a you-talking-to-me bassline and finally a burgeoning guitar signature that sounds like welling anger.

Some days, I still can’t believe this is the same band that later put out the blaringly arid “Don’t Answer Me,” which sounded like Phil Spector on downers. This song sizzles. — Nick DeRiso

“(THE SYSTEM OF) DOCTOR TARR AND PROFESSOR FETHER,” (TALES OF MYSTERY AND IMAGINATION: EDGAR ALLAN POE, 1976): “Tarr And Fether” is a guitar riff song, which isn’t that big of a deal except that it’s also an Alan Parsons Project song. Which means it’s done with maybe a little more refinement and fussy production, and there’s little time for six-string wankery: this song’s got what must be the world’s shortest guitar solo. But the tune’s got a little funky electric piano countering the riffs and the combination of the two feels just right.

Those familiar with other tracks on APP’s debut will find quotes from “A Dream Within A Dream,” “The Raven” and “The Tell-tale Heart” inserted throughout this song, making it virtually a summation of the ol’ vinyl Side 1. This was also Parsons’ first attempt at some radio action, but it only scraped the bottom of the American Top 40 in 1976. The grand NBA entrance tunes would come a few years later.

Party revelry at the beginning of the song, applause near the end and lines like “keep on handin’ the jug round/All that you need is wine and good company.” Hey, I’m no literary expert but what the hell does that have to do with Poe? Eh, it doesn’t matter. Parsons has been known to rock out a bit once in a while, but he’s never made it as fun as he did here. — S. Victor Aaron

“LUCIFER,” (EVE, 1979): I sat in this glassed-in room, at the local stereo shop, hoping to make my first purchase of a pair of those long-dreamt-of tower-speakers. The guy talked about brand names, and I nodding knowingly — not knowing, of course, but wanting to appear to know. I moved from one to another, listening to the sound envelop me. Over and over, he played “Lucifier,” an instrumental that certainly seemed like something my parents would hate. Even better, right? “This song has the depths, and the range, to show you what this speaker can do,” the salesman said.

I had a heard a few radio tracks, by this time, from the Alan Parsons Project. But you could forgive me — or anybody, really — from not knowing who they were and for not recognizing the opening instrumental from their 1979 release Eve. What I remember, even now, was how “Lucifer” leapt out from this new technology. Those big-box speakers were different, so viscerally different, from the shelf models I had back home.

Oh, I was buying the Technics. The turntable, the receiver, the speakers that came up to my waist. All of it. I lugged it all home, plugged it all in, and listened to this song again, safely ensconced in the woodpanelling of my childhood — but yet forever changed by a world of equalizer settings, pre-set radio-station buttons, a volume knob the size of my fist and, yeah, Alan Parsons. — Nick DeRiso

“THE VOICE,” (I ROBOT, 1977): With a wah-wah guitar, a circular bass pulse and dramatic symphony swirls, it might be Alan Parsons circa 1977 but it conjures up the Temptations or Isaac Hayes, circa 1971. Regardless, this song — an odd hybrid of “Papa Was A Rolling Stone” and “The Theme From Shaft” focusing on the prescient idea of being under constant surveillance — had a couple of cool things about to go along with the pimped-out groove.

For one, it’s got an actual bass solo in the middle (OK, so the lines might have been completely scripted, but still) that’s played amidst these string swirls, a chukka-chukka guitar and handclaps. And then there’s a vocoder growling “he’s gonna get you” finishing the end of the lines sung by a very British-sounding Steve Harley.

A ’70s British art-rock outfit trying its hand at a blaxpoitation film song was probably not the fashionable thing to do at a time when that kind of music was starting to go painfully out of style. Today, though, it’s a cool example of early-’70s black music … from a mid-’70s English group. — S. Victor Aaron

“LA SAGRADA FAMILIA,” (GAUDI, 1987): This was the opening tune on what would become one of the final Alan Parsons Project, er, projects — dedicated to the Catalan architect Antonio Gaudi. His life’s work, the Sagrada Familia Cathedral in Barcelona, remains this dramatic enigma. Meant to be completed over hundreds of years, it was perfect for Parsons and Co., right?

Sounded like a return-to-form in the making, after a few years of doughy radio hits. Too, they had done similar conceptual projects before, notably basing their debut on the works of Edgar Allan Poe — and this seemed to hold the same depth and complexity. But the times, inevitably, had changed. That’s something you sense APP striving to come to terms with, say, on the misplaced John Miles-sung rocker “Money Talks.” Only the opener, and the thrilling instrumental closing track, seem to match the grandiosity of their subject’s sweeping vision — not to mention the old Alan Parsons Project itself.

Still, give credit to Parsons and longtime partner Eric Woolfson, working again alongside orchestral flourishes by Andrew Powell, for trying to return this group to its original intent — just in time, unfortunately, to break up. Woolfson would later be tragically felled by kidney cancer in 2009. — Nick DeRiso

Well, sort of their last album. I asked Alan Parsons about this.

“Don’t look for Freudiana at the record store under Alan Parsons Project. Aside from expensive European imports, the disc has barely existed in the U.S. market, and while the band members are present, the final album exists in a gray area.

“There is an odd symmetry to this nearly being the last Project effort. Vocalist John Miles was on their first album with the track “(The System of) Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether.” Miles closes Freudiana with the

show-stopping “There but for the Grace of God.” Maybe “show-stopping” is the wrong phrase. ”

‘A producer, Brian Brolly, had worked with Andrew Lloyd Webber on some of his musicals; he got involved. It had been a single album tracklist, but then we doubled up the music, and took it to the stage in Vienna where it ran quite successfully for a year as a staged, Broadway-styled musical. Although I thought the album

was good, (the play) wasn’t my cup of tea. It wasn’t something I was very proud of. I’m not really one for Broadway vocal styles.’

http://www.newjerseystage.com/articles/getarticle.php?ID=4482