Jimmy Cobb, the lone survivor of legendary jazz dates featuring Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Dinah Washington, Wes Montgomery and others, continues to furiously drum — even while carrying the torch.

The 82-year-old’s newest album is called Remembering Miles. Cobb will also begin a tour celebrating the music of Coltrane on Thursday, continuing through Nov. 5 with Javon Jackson, Mulgrew Miller and Nat Reeves. Each project, in its own way, celebrates collaborations on Davis’ Kind of Blue, Sketches of Spain and Porgy and Bess, among others; as well as memorable turns on Coltrane’s Bahia and Giant Steps.

Still, that only tells part of Cobb’s life around jazz. He did his first recording with Earl Bostic, and played with Washington, Billie Holiday, Clark Terry, Dizzy Gillespie and Cannonball Adderley — all before a stint with Davis from 1957-63. Later, Cobb worked with Wes Montgomery, Kenny Burrell, Wynton Kelly, J.J. Johnson, Sarah Vaughn, Sonny Stitt, Joe Henderson and Dave Holland, among many, many others. More recently, Cobb has turned his focus toward a third-act career as a band leader. After releasing just two such dates through 2001, Cobb has since produced at least nine more — and been honored as a recipient of the NEA Jazz Masters Award along the way.

In the latest Something Else! Sitdown, Cobb recalls a few of these legendary moments, from his spur-of-the-moment decision to join the Miles Davis band to a romantic entanglement with Dinah Washington — and then makes an impassioned call to a younger generation to rediscover his music …

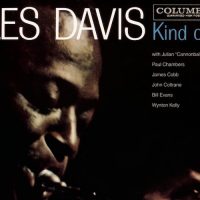

NICK DeRISO: Kind of Blue has become the best-selling jazz album of all time, a touchstone moment in music. But that moment — there in the studio with Miles — was actually sort of thrown together. There were almost no rehearsals. How did you get in sync so quickly?

JIMMY COBB: My mindset was, it was just another Miles Davis date. I had no idea what the concept was. All he told me was the key signatures, the rhythmic patterns — things like that. He figured anything he did would come out alright, because of the personnel. Those guys were all top-notch musicians. He knew we could handle anything he had. He told us what it was, and we proceeded to do it. Everything took about one take. Miles made us stop to redo the blues thing with Wynton (Kelly, who sat in on “Freddie Freeloader,” above), because he didn’t like a chord he played in the turnaround. Other than that, it was all in one take. It all happened in two days, one week and then a couple of weeks later.

NICK DeRISO: You were introduced to the band through Cannonball Adderley, right? How did the two of you meet?

JIMMY COBB: I met him when I was working with Dinah Washington’s trio. We were checking into a hotel before a date in Florida, and he was waiting to meet us. He wanted to know what was happening in New York, because he was contemplating leaving. He was talking to me about guys like Sonny Rollins, what the scene was. He was feeling it out, and we got to be friends. A little after that, he put a band together — guys from his hometown down there: Junior Mance, who had been in the Army with him; Curtis Fuller and Sam Jones. They came to New York and found an agent, and they sounded good — but decided they wanted a new drummer. Cannon called me up, and I got the gig to make the record Cannonball’s Sharpshooters. They ended up getting into some trouble for not paying their income taxes, and had to break the band up. Later, after he got the gig with Miles, Miles had Philly Joe (Jones), Paul (Chambers), Red (Garland) and (John) Coltrane. He made it a sextet. At that time, Philly Joe was missing some of the jobs every now and then — and Cannon wanted to keep the job and not have anything funny happen. He needed the money! So, he mentioned me as a fill in, if Philly didn’t show. Miles called me one night at about 6 in the evening and said he wanted me in the band. I said OK. We talked about it, and I asked him: ‘When are you working next?’ ‘Actually, I’m working tonight — in Boston.’ He’s already in Boston! I said, what time does it start? ‘Nine.’ It’s six — and we’re 400 miles apart! How am I going to get to Boston by 9? He said: ‘You want the gig, don’t you?’ So, I got on a shuttle running from New York to Boston. By the time I got there, they were playing already. I think Miles wanted to start on time, because he didn’t want to have trouble with the money. They were playing “’Round Midnight.” I set my drums up while they were playing. When they got to the spot where there’s a little break before the solo, I joined in. I played that with them and I was in the band. No rehearsal, nothing.

NICK DeRISO: Later, you, Chambers and Kelly backed Wes Montgomery. Perhaps the high point was the aptly titled straight-ahead live album Smokin’ at the Half Note. Were you surprised when Wes later took a turn into more pop-influenced styles?

JIMMY COBB: He did that because he was talked into it, probably by (producer) Creed Taylor, who told him: ‘You could make some bigger money. You could be more public, playing all of those tunes.’ He didn’t like it. He was doing it because he needed the money. He had about 9 kids, so he figured he had to go for it. While he was still home, he had three gigs! He worked all day and all night — never got any sleep. It made his heart bad. One was construction; I think he worked on a jack hammer. The second one was as a guard for a milk company. And then the third was playing music! That took its toll on his energy and his life.

NICK DeRISO: You mentioned Dinah Washington. Over the years, you’ve played with a number of vocalists, from Sarah Vaughn to Billie Holiday, from Carmen McRae to Shirley Scott. But you had the deepest regard, it seems, for Washington. What was so special about that relationship?

JIMMY COBB: We were together, I guess you would say, socially after a while. I met her when I was 21 years old. I went on the road with Earl Bostic, and our attraction was Dinah Washington. She had been traveling with Wynton Kelly, and that’s how we met. After that, we got to be partners. That’s how that went. I took over as her management and did those chores, too. We were together three or four years, maybe. Some people try to sound like her — Esther Phillips for one, but she never quite made it. Dinah was very, very special.

NICK DeRISO: What took you so long to begin a career as a solo bandleader? Your debut, So Nobody Else Can Hear featuring Freddie Hubbard and Gregory Hines, didn’t appear until 1981.

JIMMY COBB: I never was thrilled about being a bandleader. Most of them tend to write music and I couldn’t do that. I figured I didn’t want to be in that until I could really contribute. The first record with my name on it came about because of the encouragement of my wife Elena Steinberg. She produced the record, and it came out pretty good. There were a lot of great people on it — including Gregory Hines, who sang on three tunes. At that time, a lot of people did not know he had that good of a voice. Then, the rest followed. By that time, I was around a lot of young guys who wanted to play with me because I had played with all of these people. My wife is still the producer and she has done five records for me for Chesky Records. Some of my favorites (as a leader) include Four Generations of Miles (with saxophonist George Coleman, bassist Ron Carter and guitarist Mike Stern, in 2002). There was one (2005’s New York Time), with Cedar Walton and Christian (McBride) and myself. Lately, we’ve made a couple of ones with Roy Hargrove (including 2001’s Yesterdays, 2007’s Cobb’s Corner and 2009’s Jazz in the Key of Blue). I did a record for Branford Marsalis (2006’s Marsalis Music Honors Jimmy Cobb), too. There was a lot of drums on it; that’s what he wanted, I guess. Just recently, I started writing a few tunes. It’s pretty cool. I’m still trying to do some things I never did before.

NICK DeRISO: This week, you’re kicking off a new tribute tour featuring John Coltrane’s music. Is it important to you, as one of the last representatives from that era, to do as much as you can to expose this music to a new generation?

JIMMY COBB: I’m just happy to still be around! But, yes, you have to keep the music alive. People that hear the stuff from Kind of Blue, even after 50 years, they still like it, too. But it’s harder to get through sometimes. Young people might be listening to rap, but we don’t want them to stop listening to jazz, either. So we go out and play these songs. Like last time, we’ll call it ‘We Four.’ We’ll play Coltrane tunes like “Naima,” “Little Old Lady,” just the things that he played. We hope to keep it alive for a younger generation.

- Nick DeRiso’s Best of 2015 (Rock + Pop): Death Cab for Cutie, Joe Jackson, Toto + Others - January 18, 2016

- Nick DeRiso’s Best of 2015 (Blues, Jazz + R&B): Boz Scaggs, Gavin Harrison, Alabama Shakes - January 10, 2016

- Nick DeRiso’s Best of 2015 (Reissues + Live): John Oates, Led Zeppelin, Yes, Faces + others - January 7, 2016

Jazz in the key of Blur

New York Time

West of 5th

Cobb s Corner

Fom Chesky Records