by Something Else Reviews

Anybody who names his first four solo recordings after himself is going to require some deciphering, right? We’re here to help with a five-song spin through Peter Gabriel’s solo career, featuring both charting favorites and a few forgotten gems.

By Tom Johnson

With Gabriel’s first solo album, “Here Comes the Flood” arrived bearing the weight of a full band, then shed most of the instrumentation for another appearance on Robert Fripp’s solo album, Exposure. Bookended by a pair of fitting and beautiful washes of Frippertronics, the shorter opening part was accompanied by a tape of Fripp-mentor J.G. Bennett discussing the repercussions of mankind’s behavior toward the environment. That must have sounded like ridiculous scare-mongering to most back in 1979 but it now has seemingly started to come true — exactly when he suggested it would.

A final, seemingly definitive official version of the song found its way to Gabriel’s hits package, Shaking The Tree, in 1990, completely re-recorded. Just Gabriel and piano, this version hits all the emotional notes just so, being at what seems to have been the peak of his vocal performance period. Just enough of that velvet smooth tone from his younger years, just enough of the gruff signs of age that have begun to creep into his voice. It sounds a weary warning, and the lyrics take on more power.

What of those lyrics? What is going on here? It sounds vaguely Biblical — floods, swollen tide, silent seas and all. And that’s just the angle Fripp was working with his Bennett quote. Being Fripp’s album, it’s his decision to add an interpretation to the song like that, but it has understandably colored my own feelings about it. It appears it is totally, completely wrong.

At the time he wrote it, Gabriel was intrigued by short-wave radio, and found himself thinking how radio signals increased in the night air. He dreamt one night that the barriers that hold back our psychic powers had breached, and night fall predictably increased the power to reach into others’ minds. Some would be able to handle it, many would not. “It’ll be those who gave their island to survive” — no man is an island, indeed.

In many songwriters’ hands, an idea like this would come off as sci-fi junk — an embarrassing mess of cliches and and an overabundance of ideas. Peter Gabriel’s writing skills were advanced enough to cloak his complex, possibly off-putting idea behind a beautiful melody and clever allusions, and, most importantly, leaving room for interpretation.

By Nick DeRiso

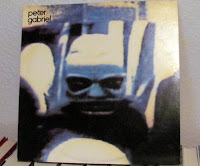

With his fourth consecutive self-titled release (the record label added a sticker that said Security), Peter Gabriel sets the stage for every commercial breakthrough just over the horizon.

That means experiments with electronic gadgetry, like the Fairlight-driven “San Jacinto.” He continues to dabble with African and Latin beats. “Wallflower” even approximates the orchestral majesty of later, more fully realized anthems like “In Your Eyes.” And it means a weirdly compelling single, with a nutjob lyric and the accompanying can’t-take-your-eyes-off-it video. On 1986’s So, that was “Sledgehammer”; here, it’s a stammering little freak-out called “Shock the Monkey.”

Gabriel’s initial Top 40 hit in the U.S., at first, seemed to be about animal rights, maybe? No, electroshock therapy. OK, mankind’s primal desires? Whatever the lyrical intent (Gabriel later said “actually, it was a song about jealousy”), this pulsing polyrhythm -– augmented by an itchy, relentless four-note keyboard hook -– shoots the tune through with a spooky urgency. You might now have known what the hell it meant. But you could scarcely forget “Shock the Monkey.” Previously a cult figure, Gabriel was inching toward a zeitgeist-shifting breakthrough.

By S. Victor Aaron

Gabriel plainly explained that “Big Time” was “a satirical story about a basic human urge … success,” but the timing of that song couldn’t have been more prescient as it became and radio and dance floor hit during the height of all the investment banking hype. Milken, the Michael Douglas movie “Wall Street,” corporate takeovers, leveraged buyouts, junk bonds and thirty-year-old millionaires on the cover of Fortune magazine became the order of the day, inspiring a mini-generation of starry-eyed business school students with dreams of snagging just a low-paying eighty-hour a week internship with Goldman Sachs, Salomon Brothers or Morgan Stanley.

I was at b-school at the time too, but the lottery’s chance of obtaining a lifestyle that comes with the nasty side affect of intense pressure where success depended so much on the shifting and unpredictable winds of the market in the end didn’t seem to be my destiny. Gabriel’s song, which is one big moment of sarcasm, brought home the point about the shallowness of pursuing wealth and glamor for its own sake, lecturing at the exact time such a lecture was needed. But with an irresistible pulse constructed by Stewart Copeland’s drums and three … three … bass players (that’s Tony Levin bouncing drumsticks off the bass strings during Gabriel’s layered, cascading harmony break), everyone was too busy partying to the song to care about the message.

If anything, society has since buried the message deeper. As deep as that infectious groove.

by Nick DeRiso

He was a singer who, to this point, was too prone to overstatement. (That continued elsewhere on Gabriel’s second self-titled solo release, you could argue, with the somewhat pedantic anti-war screed “Games Without Frontiers.”) But not here, as Gabriel constructs a brilliantly understated anti-apartheid song in memory of slain South African activist Stephen Biko.

The album version begins and ends with a shattering rendition of “Senzeni Na? (What Have We Done?),” a traditional Zhosa/Zulu song performed at Biko’s funeral. Struck by his vicious murder at the hands of the police, Gabriel reveals a raw emotion: “The man is dead,” he repeats, chillingly. “The man is dead.” With that fiercely honest lyric, he expertly balances along a very difficult line, dealing with a political issue and with a martyr. Gabriel wouldn’t have been the first musician to succumb to prosaic speechifying or, worse really, to mawkish sentiment. Instead, here and elsewhere on perhaps his first solo masterwork, Gabriel began exploring his own emotions in a compelling turn inward -– something that would define his career.

A complex effort both musically and lyrically, Melt was initially rejected by Atlantic Records, becoming Gabriel’s only release on Mercury. Over time, though, this record has started to sound more and more influential, like the first utterances of an artist finally finding his own voice. (The towering echo effect used on Phil Collins’ drums during “Intruder,” for instance, became Collins’ signature sound after its inclusion on “In the Air Tonight,” from his subsequent release Face Value.) Melt would eventually be ranked No. 45 on Rolling Stone magazine’s list of the 100 greatest albums of the 1980s.

By Tom Johnson

Us is a relationship album, with a heavy emphasis on the fragility of the ties that bind us to each other, the hidden world we each keep from the other in those relationships, and how easily all that can be betrayed. Gabriel takes full advantage of the middle-eastern and African rhythms he’s so fond of to effectively show how we’re all different as well as how united we are. It’s something he’s grown to be expert at, working in little bits of it here and there (most people will be familiar with the African rhythms that show up at the end of “In Your Eyes.”) It’s his way of exposing the elements that weave through all styles of music, a way to break down boundaries between people. Here he uses different cultures’ instruments and musical styles to illustrate the nature of relationships. That said, who would have guessed that of all things Peter Gabriel would explore, gospel would be where he might expose his most vulnerable side?

“Washing” stands out on Us because of its simplicity, lacking the polyrhythms of its multi-cultural album-mates (“Love To Be Loved,” “Blood Of Eden,” “Only Us,”) the upbeat dancability of “Steam” and “Kiss That Frog,” or the dark groove of “Digging In The Dirt.” It’s an almost raw tune, focused entirely on Gabriel’s voice over minimal backing of piano and drums for much of its length, until an emotive outburst takes the song to its climax. But it’s the songs lyrics that truly

carry the weight. Where one could get by enjoying Gabriel’s clever musical ideas in other songs, it’s impossible to ignore a deep message he wants listeners to pay close attention to in this one.

“I’ll get those hooks out of me / And I’ll take out the hooks that I sunk deep in your side” — it’s a beautifully painful lyric that illustrates just how destructive two people can be to each other when love turns sour, and how the only way to find any salvation is to understand that each of you has inflicted the same damage upon the other. Here, Gabriel as the song’s narrator, takes responsibility of taking the first step toward accepting responsibility for his own regrettable actions toward someone he once loved, in hopes that perhaps the move will be reciprocated. Mostly, however, it is to soothe the anguished soul that has been lamenting his position in limbo, the river, throughout the rest of the song. Instead of asking for the river to bear his weight, and the burden of his guilt, he now simply asks that the river help take his pain away.

While we’re left with some semblance of resolution, the ending is not what most would consider “happy.” But it’s real, and that’s the message: What we do as revenge for slights, both real and perceived, doesn’t result in solutions. Maybe, in some ways, the message is that resisting that urge would instead make people work at being together, rather than simply resorting to “hooks sunk deep in your side.”