In late spring of 1972, Miles Davis broke a two-year hiatus from the studio to act upon the most daring idea of his 45-year recording history: Creating music that was completely absent of any jazz aesthetic. Instead, as the title suggests, On the Corner focused on a more “street” sensibility. He’d jettison most instrumental wankery in favor of moods and heavy grooves, a counter move in 1972 if there ever was one. Further, Miles Davis abandoned discernible melody in favor of bass riffs and relentless repeating figures and beats.

Featuring songs with no beginning and no end, On the Corner arrived on October 11, 1972 as one of his most controversial albums. But unlike Miles Davis’ other controversial albums, many fans still refuse to embrace it — even today.

To put this vision into vinyl, Miles enlisted the help of an acquaintance he met three years prior — the premier orchestral conductor for rock stars, Paul Buckmaster. A British cellist whose arrangements had already by this time figured in prominent records by David Bowie, the Rolling Stones and Elton John, Buckmaster always harbored a love for the avant-garde and jazz. So, when he got the call from Miles Davis, he enthusiastically embraced the opportunity.

In the process, Paul Buckmaster encouraged Davis to assimilate some of the music theories of Karlheinz Stockhausen, the German composer who pioneered the use of electronic instruments in classical music and formulating alternative song structures. Whether it was conscious or not, Miles moved more toward Ornette Coleman’s harmolodics, requiring most of the musicians to play with as little preconceptions as possible and listen closely to each other.

As Buckmaster consolidated his ideas and composed scores, Miles rounded up another stellar set of supporting musicians for the task: John McLaughlin, Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, Lonnie Liston Smith, Jack DeJohnette, Billy Hart, Dave Liebman, Bennie Maupin, Al Foster, Michael Henderson, Don Alias and many more. Just as significant, Indian players were used (Badal Roy, tablas; Khalil Balarishna, electric sitar; Colin Walcott of the band Oregon, sitar). The Indian experimentations actually begun toward the end of 1969, and lasted until Miles took a break from the studio a few months later. But now, there were more earnestly employed.

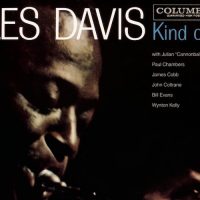

Never before or since had Miles assembled such a massive amount of talent nor had utilized such a wide array of influences to make a record. Unfortunately for Paul Buckmaster, his own best laid plans were largely tossed aside when the recording sessions began on June 1, 1972. Some of the basic ideas he brought to the sessions came to function as starting points, and even then the assembled musicians and producer Teo Macero took them to places he never intended. Otherwise, his carefully constructed scores went unused. Few of the assembled musicians saw any rehearsal at all. This was how Miles Davis coaxed spontaneity out of his players, much as he had done for many of his notable records dating back to Kind Of Blue.

There were two primary sessions where all the basic tracks for On the Corner were recorded. The title was put to tape on June 1, with “Black Satin” following on June 6. These two megatunes were later broken up into the four, discrete tracks that make up the final release. Two of those tracks were further broken down into arbitrarily defined songs within the track, though neither had identifiable starting and stopping points.

The unedited master of “On The Corner” is one of the rare spots on the album where a soloist aside from Miles emerges from the ensemble: John McLaughlin sounds more like his old, uninhibited Jack Johnson self, instead of the more studied, Mahavishnu version. The album version, called “On The Corner/New York Girl/Thinkin’ of One Thing and Doing Another/Votes For Miles” is not that much changed from the raw version.

The Complete ‘On the Corner’ Sessions, a comprehensive posthumous box set, revealed another previously unreleased nugget from that session: “On The Corner (take 4)” sounds like a different tune altogether. Instead of the quicker double-time of the 20-minute version that ended up on the original album, this five-minute rendition goes at a slower pace and McLaughlin’s menacing guitar fronts an un-worldly percussion section full of Indian instruments, conventional percussion and drums (either Hart or DeJohnette, or both). Beside a sitar and Yamaha organ bleating out dark chords lies Michael Henderson’s rock-solid bass vamps at the center. Miles himself lays out. “Take 4” is a little bit light on the cerebral side, but it’s one of the best straight groovers on the whole box set. With Henderson and McLaughlin leading the way of this jam, it’s marks a brief glimpse back to 1970’s Tribute To Jack Johnson.

The centerpiece track of both the original album and the subsequent 2007 box set is “Black Satin.” In a collection consisting of hours upon hours of cyclical grooves and two-note riffs, “Black Satin” is beautifully complex, mysterious and downright funky. Despite it being derivative of the initial “On The Corner” track that spawned many of the other cuts here, “Satin” stands apart because of the heavy editing and dubbing that had been largely avoided for the other selections. It also possesses a catchy, recognizable theme. The rhythm is heavily multi-layered and the whistles and almost-random hand claps add a “street” element to what is actually a free-form funk tune. Teo Macero made heavy use of tape edits that predate the sampling and beats that would underpin techno, drum ‘n’ bass and dance music many years later. For all of these reasons, “Black Satin” remains the most successful expression of Miles Davis’ genius over the last two decades of his life.

Key moments that ended up on 1974’s Get Up With It and the odds-and-ends collection of early fusion songs Big Fun add new dimensions to On the Corner.

“Rated X,” also found on The Complete ‘On the Corner’ Sessions, is not even a song, but a seven-minute jungle groove that’s particularly nasty. The innovative aspect of it is how the percussion starts and stops at random, as if someone accidentally mixed it out of the track in spots. Intentionally or not, the rhythm coming in and out in that manner was what Paul Buckmaster had intended for the On The Corner sessions. Miles doesn’t play trumpet but provides some eerie organ chords made tightly packed by tape loops created by Teo Macero. That seems like a goof until you consider it anticipated techno, or electro-dub and sampling by some 15 or so years.

Another track to note is “What They Do,” which is more rock-oriented than funk-oriented. It seems to be played by the 1973-75 lineup of Pete Cosey and Reggie Lucas on guitars, Henderson on bass, Mtume on percussion and Foster on drums. I’m guessing that it’s Cosey with the wah-wah freak-outs, but Miles is soloing right along with his wah-wah trumpet. A decidedly more “live” feel than other studio tracks of that time, it a striking reminder that Miles Davis’ best albums between On the Corner and his retirement in 1975 were concert recordings.

“Ife,” originally released on Big Fun, was recorded six days after “Black Satin,” and it’s not entirely clear why the track wasn’t included as part of On the Corner. The 20-plus minute opus is credited to Davis but, according to Buckmaster, the main melodic line and the chord progression were his. Michael Henderson supplied the bass line; Buckmaster also plays electric cello on it. Probably too long by about six or seven minutes, there is enough going on musically to make “Ife” more interesting compared to most of the other tracks recorded in this period. Miles certainly held a fondness for the track; it was a regular in his concert rotation for the next few years.

Much of the rest of what we find from the period, however, struggles to distinguish itself because of Miles’ numbingly repetitive grooves and lack of melodic structures. Decades later, as Davis biographer Paul Tingen rightly notes, this particular Miles Davis era “continues to be challenging listening. The absence of musical structures, harmonic development, and melodic content poses genuine problems.” As such, Miles Davis’ On the Corner still hasn’t reached the mainstream acceptance levels of fusion predecessors like In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew.

That said, the best of On the Corner remains forward-looking, fresh, and funky. Like Corky McCoy’s notorious album cover from the original release, the question of whether this is a masterpiece, an inferior sketch or a mixture of both is in the ear of the listener. One thing is for certain, though: It’s very much an original.

- Ivo Perelman + Tom Rainey – ‘Duologues 1-Turning Point’ (2024) - May 10, 2024

- Jeff Oster, Vin Downes + Tom Eaton – ‘Seven Conversations’ (2024) - May 6, 2024

- David Torn – ‘Adityahridayam 321’ (2024) - May 5, 2024