Of all the King Crimson incarnations (the historic first LP with Greg Lake, the Jamie Muir/Bill Bruford percussion battles on Larks Tongues in Aspic, the Bible Black/Red period, the Discipline years), I found the Thrak era enthralling — because of its dual-drummer (well, dual-everything) format.

The double-trio — so named because of its unusual lineup of two guitars, two basses (well, things along those lines — bass and Stick-like touchstyle instruments), and two drummers — was meant to create an ungodly amount of noise in the most spectacular way possible. Unlike, say, the Allman Brothers, who used their two drummers to made one strong, united rhythm section, King Crimson used its two drummers in a push-pull arrangement, playing off of each other, tugging at rhythms, often splitting up and going head to head to do things that one drummer could not.

It was one of those concepts that belonged more to jazz than to rock and which, at the time — King Crimson’s Thrak was released on April 25, 1995, right in the middle of the minimalistic grunge and alternative movements — garnered a lot of snickering from the press for being excessive and indulgent. As longtime leader Robert Fripp has pointed out, though, the band often seems to take a lot of abuse at the time it does something unusual, only to see that move take on more importance when history has a chance to look back on it.

Once again, that has indeed been the case. The double-trio found on Thrak was a fantastic, boundary-pushing live band, if nothing else, and years later many of us are gaining a new appreciation from the many live releases from this period.

[SOMETHING ELSE! INTERVIEW: Tony Levin on the double-trio format — “We trusted in Robert Fripp’s judgment that the direction would be new and worthwhile. The result did justify that trust.”]

King Crimson’s double-trio never really became as fleshed out as it should have been, unfortunately. There was but EP, one album and a very long tour that spawned those many live albums. Then they dissolved with drummer Bill Bruford and bassist Tony Levin going their own ways. Just prior to this unfortunate lineup change, the ProjeKcts (a series of exploratory concerts by members of the six-piece band in varying numbers and roles) proved that there was a lot of ground left to be covered, but Bruford had lost interest.

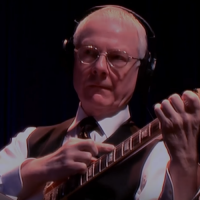

He wanted his own jazz band, the acoustic Earthworks, to be his primary concern. Why Tony initially moved on, I’m not entirely sure anymore, but it certainly wasn’t due to any bad blood. He did, after all, return to the band after Trey Gunn later opted out — and just as it was thrilling to have a master of “touch guitar” like Gunn on board, it’s always refreshing to see Tony Levin on basses and Stick.

Two subsequent King Crimson albums from this new slimmed-down quartet unfortunately didn’t seem to garner as much attention as the double-trio did — the one that seemed to take quite a ribbing for being so excessive. Apparently all that excess did do one thing after all. It got King Crimson a lot of notice.

So, why, following Thrak, didn’t Crimson keep pushing forward with that format? One of the problems cited by many was that, when it came to the double-trio, the additions brought to the sound by the two extra musicians was just too subtle most of the time. Whatever the reason, the double-trio never got the chance in the studio to really take on its own life, despite having existed for well over three years.

[SOMETHING ELSE! INTERVIEW: Adrian Belew on the double-trio format — “We worked out something truly unique. I have always wished that we had used the two-trio thing a little more radically than we did.”]

It was only on the road that it developed itself — but this was after one EP (VROOOM) and their lone studio album (Thrak) had already been recorded. The band had intended to record Thrak in such a way that two sets of trios would play at the same time (say, Bill Bruford, Try Gunn, Robert Fripp and drummer Pat Mastelotto, Tony Levin, second guitarist Adrian Belew) but in slightly different ways (time signatures, etc.) that would be separated in the sound field.

In theory, it sounds fascinating, and is a real challenge to the way rock music can be approached. In practice, however, the band, well, didn’t. The only real example of this approach to be found is “VROOOM”: Pan your speakers left or right and you’ll hear two separate trios playing, you guessed it, slightly different versions of the same song. They merge back together as “Coda: Marine 475” begins. As promising as the idea had been, it proved too much to accomplish an entire album that way at the time.

Later, DGM made available two sets of studio rehearsals, one from the sessions for VROOOM and another after the Thrak tour, both of which give glimpses of what Robert Fripp and Co. might have achieved. As can be guessed, what we get is rough and incomplete — but, for fans of King Crimson, fascinating for what we missed out on. There are plenty of ideas that the ProjeKcts and the quartet ran with, but not in quite the way that the double-trio would have.

King Crimson has since re-emerged in still another format, this time with three drummers along the front line. Unfortunately, that leaves only the occasional tour from the offshoot Crimson ProjeKCt, which features Tony Levin, Adrian Belew and Pat Mastelotto, and they offer just a partial glimpse back to this brief, but important, period.

- How David Bowie’s ‘Reality’ Stood Out For What It Was Not - September 29, 2023

- Metallica’s ‘St. Anger’ Was Always Much Better Than They Said - June 8, 2023

- How King Crimson Defined an Unsettled Post-9/11 Landscape on ‘Power to Believe’ - March 5, 2023