Former Wings members Denny Seiwell, Henry McCullough and Laurence Juber — a trio of figures who span either end of the 1970s-era Paul McCartney band’s lifespan — offer unique insight into their old boss’ music.

Seiwell appeared on McCartney’s 1971 effort Ram, then became a co-founding member of Wings with Paul, Linda McCartney and ex-Moody Blues frontman Denny Laine. They’d release Wild Life in that configuration before McCartney added guitarist Henry McCullough — who was then best known for his work with Joe Cocker and Spooky Tooth.

McCullough and Seiwell would leave in 1974, but only after having helped catapult Paul McCartney and Wings to the top of the charts with “My Love,” from Red Rose Speedway. That lineup of the group also issued a celebrated theme for the James Bond film “Live and Let Die.”

Seiwell returned to jazz, his first love, while McCullough has more recently suffered debilitating health problems. Laurence Juber, meanwhile, was part of the final, always deeply underrated edition of Wings.

Between 1978-81, they’d have a hand in the chart-topping “Coming Up,” the No. 5 hit “Goodnight Tonight,” the Grammy-winning “Rockestra Theme” and Back to the Egg, Wings’ platinum-selling finale. Juber now works as a virtuoso solo guitarist.

Band on the Run, and more recently Wings Over America, has always gotten all the press. But together, this trio witnessed — and helped shape — their own memorable, though typically ignored music during McCartney’s immediate post-Beatles career …

“ARROW THROUGH ME,” (BACK TO THE EGG, 1979): Maybe the most unjustly forgotten McCartney single, this R&B-infused soft-rock pastry – featuring a Fender Rhodes-y bassline straight out of the Stevie Wonder playbook, and an endlessly inventive undulating polyrhythm from drummer Steve Holly – somehow only peaked at No. 29 as a U.S.-only single.

“That’s a killer song and, I think, one of Paul’s most underrated compositions,” final Wings guitarist Laurence Juber tells us. “It’s been forgotten because rock radio has only embraced the stuff that got the heavy airplay. I think it was Steve’s idea to do the double-speed drums. There are two drum parts — the regular drum part and the double-speed part. Of the Wings drummers, Steve Holly was the most classic English rocker of all. Denny Seiwell was a great drummer, but he was basically an American jazz drummer. Joe English was a American style drummer, too, whereas Steve, of all the drummers that Paul has worked with, was probably the one that played the least like Paul — and the least like Ringo. Paul has the tendency to choose drummers that play more like him, or more like Ringo. But Steve Holly stands out, because he comes from a different space.”

Couple that with a bright blast of horns (played by fonky group fronted by Thaddeus Richard, but mimicked on the keyboard by Juber in the accompanying video) and the result is a long, long (maybe too long?) awaited update of what had become Wings’ tried-and-true silly-love-song template.

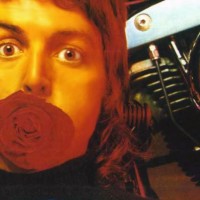

“MY LOVE,” (RED ROSE SPEEDWAY, 1973): This heavily orchestrated gold-selling ballad shot to No. 1 in the U.S., and reached No. 9 in the UK. It’s most memorable element, however, came courtesy of McCullough, who fought for his own solo moment on the song.

“It was like playing a hand of cards, and having a royal flush,” McCullough told us, before his recent struggles. “Paul had this particular thing that he wanted me to play. That was the point of no return. I said: ‘I’m sorry, I can’t do this. I have to be left as the guitar player in the band. I want to have my own input, too.’ He says: ‘What are you going to do?’ I didn’t know. I simply said: ‘I’m going to change things.'”

McCullough, whose flinty sense of individualism led to his departure just before Wings’ next album, would have to nail his “My Love” solo live in the studio: “I was half terrified, half excited. I just started playing, and that’s how it turned out — just as you hear it. That flabbergasted Paul, and there was just silence for a while. I thought: ‘Uh oh, I have to do it again.’ Paul came over and said: ‘Have you been rehearsing?’ (Laughs.) I liked to have that freedom. I wanted to put my cards on the table. He asked me in the band, but I didn’t want him to tell me what to play.”

“COMING UP,” (SINGLE, 1980): Originally issued as the opening track on Paul McCartney’s 1980 solo synthesizer experiment McCartney II, “Coming Up” became a No. 1 U.S. smash when a live version performed by Wings — recorded in December 1979 at Glasgow, Scotland — was later released.

“People wanted to hear that: You take Paul singing a rock song, and people really went for that in the commercial sphere,” Juber tells us. “But even to this day, he still favors his version. He needed to be persuaded to put the live version on the American edition of Wingspan. In a sense, a lot of the McCartney II stuff sounds like demos, but that album has gained traction in a whole different area. It’s the more techno, a real precursor to the electronica, more DJ-driven stuff. It was Paul taking advantage of drum machines and dealing with basic sequencers. That was kind of a nice project for Paul, and it has had some resonance over the years.”

Still, the hit live version of “Coming Up” remains the final, lasting argument for the collaborative atmosphere of Wings, and what it could still do to advance the ex-Beatle’s initial musical ideas.

“BACK SEAT OF MY CAR,” (RAM, 1971): A soaringly constructed, yet desperately sad closing track and, for me, still the most intriguing moment on Ram.

In keeping with the rest of this album, “Back Seat” is a little unfocused — too overstuffed with ideas, too reliant on multi-tracked McCartneys, not as rustic as his solo debut and somehow tossed-off sounding anyway, simply too long — but yet still perfectly encapsulates everything that makes Ram such a wildly inventive, still deeply underrated gem: It’s gutsy and unprecious at one point and then a testament to Paul’s enduring pop sensibilities at others.

So, why has Ram gotten such a bad rap over the years?

“I think a lot of people were just mad that he was leaving the Beatles, and going off and doing his own thing,” founding Wings drummer Denny Seiwell tells us. “I think that had a lot to do with it. I know the critics really did not see the value in that record, but I just thought it was a masterpiece. It’s the best record I ever made, and I’ve made a lot of records.”

“LIVE AND LET DIE,” (SINGLE, 1973): The main theme song from the initial James Bond film to star Roger Moore, “Live and Let Die” became a Grammy- and Academy Award-nominated, gold-selling single — and it remains, of course, a fireworks-blasting mainstay of every McCartney concert appearance.

Recorded during the sessions for Red Rose Speedway, the track went to No. 2 in the U.S. and No. 9 in Britain, and opened the door for a gala experience at the film’s Hollywood opening. Wings had finally, completely made it. Yet, not long after that, McCullough abruptly quit — fed up, he says, with trying to elbow his way into the creative process.

“I never thought about it twice,” McCullough tells us. “We were supposed to go off to Lagos (for the scheduled sessions that would produce Band on the Run), and about a week before, I walked out. I regret that, the way that I did it, because it was probably the most unprofessional thing I’ve ever done in my life. That created a ripple, though, and Denny Seiwell walked out, too. I had been around for a long time, though. Very quickly, it was all ironed out. (Among his many subsequent early 1970s projects was a reunion alongside Joe Cocker, with whom McCullough appeared at Woodstock.) Once I got used to being scarce, it wasn’t a problem at all. (Laughs.) That subsides over time. Everything passes so quickly. It just wasn’t going to work out for the rest of us in Wings — until, of course, you had an apron on, if you know what I mean.”

- How Deep Cuts on ‘Music From Big Pink’ Underscore the Band’s Triumph - July 31, 2023

- How ‘Islands’ Signaled the Sad End of the Band’s Five-Man Edition - March 15, 2022

- The Band’s ‘Christmas Must Be Tonight’ Remains an Unjustly Overlooked Holiday Classic - December 25, 2016