To Canadians, as the new 2012 liner notes to this historic meeting of the jazz minds so rightly notes, Massey Hall is a building. To fans of this music worldwide, it’s something else — not a place, nearly 3,000 seats large, that has played host to literally thousands of concerts over a stirring 118-year history.

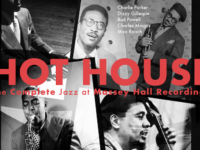

No, it’s a thing that happened: Massey Hall. Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, the yin-and-yang originators of bebop, on stage together for the last time. Bud Powell, Max Roach and Charles Mingus, there as well. And almost by chance — all of it.

The one-off date for a band only later dubbed, simply, “The Quintet” was organized by a gumption-filled group of Canadian jazz enthusiasts, held without benefit of a series of warm up dates, recorded through a single stage mic to a borrowed Ampex tape recording on a whim by Charles Mingus (who was only there when first-pick Oscar Pettiford couldn’t make it) — and then over and done with inside of an hour, over two sets in Toronto 59 years ago this month.

Jazz at Massey Hall, set for reissue on May 15, 2012 through the Concord Music Group, was initially released on the Mingus-Roach label Debut, and benefited greatly (or as much as it could) from a late-1980s digital redo by OJC. Yet another spit-shining by way of 24-bit remastering by Joe Tarantino makes it ever more clear that Mingus later overdubbed some of his own parts: The bass-playing perfectionist practically drowns out Parker on the otherwise brilliant “Hot House.”

There is also the expected sloppiness associated with these kind of thrown-together all-star outings. The story has always gone that Gillespie, a boxing fan, was stealing away during the show for updates on the ongoing fight between Rocky Marciano and Jersey Joe Walcott. Ashley Kahn, author of Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece, reveals in the new notes that the band actually took a 45-minute break so fight fans could see Walcott fall, just over two minutes into the first round.

That said, you feel compelled to forgive the moments when this group suffers a misstep. First, because they don’t happen all that often. Second, because any other amalgam of players likely would have suffered more of them.

What you hear, more often than not, is a furious cry against the dying of the light around bebop, with a series of players in their mid-20s to mid-30s clashing head on with their own past — the set was dominated by big hits from as earlier era, including “Salt Peanuts,” “Perdido” and “A Night in Tunisia” — not to mention the restless imagination of Mingus, who was still rounding into shape as a visionary leader.

Along the way, an album first presented as tribute, but then forged through staggering adversity, becomes an opportunity for re-examination.

Forget that they were, save for the West Coast-leaning Mingus, a group so closely associated with bop as to stand as its Mount Jazz-more. The framework of legend had already hardened for Parker as the doomed genius, Gillespie as the clown prince, Powell as the standard bearer and Roach as the rhythm colossus. It’s clear, though, in this album’s moments of deepest intimacy, that they weren’t ready for the embalming fluid just yet — in particular, it seems to me, Bird.

Parker — referred to as “Charlie Chan,” in honor of his live-in lover, on the original album sleeve because of contract issues — had begun by launching Duke Ellington’s “Perdido” into the stratosphere, stepping through a series of dramatic interpolations with an ease that belies his eventual fate. Then play close attention to Bird’s almost scolding presence in the traditional mid-1940s send-up “Salt Peanuts.” Parker sets the tone by introducing Dizzy, more than a little condescendingly, as “my worthy constituent.”

Elsewhere, the set seems to underscore Gillespie’s unquestioned place in the canon with pieces like “A Night in Tunisia,” but it is Parker who best acquits himself — displaying both wit and then lusty verve. With Dizzy yelping praise and encouragement, for instance, Bird eventually takes over the uptempo blues “Wee.”

This record, as much as any other from the period, makes the case for Parker one last, brilliant time. Then you think about Parker arriving without his own horn, and having to borrow a Grafton saxophone — this dinky plastic alto with metal keys. It was just one more reason why this concert should have never happened, should have been a disaster. Should have never seen the light of day.

Instead, say “Massey Hall,” and that’s what I think of: Bird in flight, for one of the last times. That’s why it’s not just a building. It’s a piece of history, a moment in time: It’s Massey Hall.

[amazon_enhanced asin=”B007R3B5WU” container=”” container_class=”” price=”All” background_color=”FFFFFF” link_color=”000000″ text_color=”0000FF” /] [amazon_enhanced asin=”B0000AJ5SR” container=”” container_class=”” price=”All” background_color=”FFFFFF” link_color=”000000″ text_color=”0000FF” /] [amazon_enhanced asin=”B0000667R1″ container=”” container_class=”” price=”All” background_color=”FFFFFF” link_color=”000000″ text_color=”0000FF” /] [amazon_enhanced asin=”B005SQ3AW6″ container=”” container_class=”” price=”All” background_color=”FFFFFF” link_color=”000000″ text_color=”0000FF” /] [amazon_enhanced asin=”B000002GL1″ container=”” container_class=”” price=”All” background_color=”FFFFFF” link_color=”000000″ text_color=”0000FF” /]

- How Deep Cuts on ‘Music From Big Pink’ Underscore the Band’s Triumph - July 31, 2023

- How ‘Islands’ Signaled the Sad End of the Band’s Five-Man Edition - March 15, 2022

- The Band’s ‘Christmas Must Be Tonight’ Remains an Unjustly Overlooked Holiday Classic - December 25, 2016