Founding Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid is playing a different tune these days – a hard-driving jazz-rock tune alongside an all-star cast of Jack Bruce, John Medeski and Cindy Blackman-Santana. Together now as Spectrum Road, the quartet has taken the idea of paying tribute to Tony Williams Lifetime to its zenith on their forthcoming self-titled debut.

Rather than following the grounding-breaking fusion template set forth by Williams, who passed away in 1997, Spectrum Road is instead using his music as an inspirational framework. The results, due June 5, 2012, through Palmetto Records, are inventive, triumphal, thunderous – a combination of the sounds associated with Jack Bruce’s Cream, Living Colour, Medeski Martin and Wood and Blackman-Santana’s memorable stint with Lenny Kravitz, but at the same time nothing like them at all.

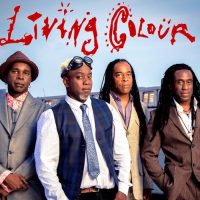

Reid, in the latest Something Else! Sitdown, talks about the genesis of Spectrum Road, a band named for an incendiary track on the initial Lifetime recording which has been growing toward this stirring debut since 2008, how jazz has informed Reid’s playing from the start – and, of course, about arriving on the scene with Living Colour’s racial barrier-bursting, heavy metal-funk classic Vivid in 1988 …

NICK DERISO: It’s interesting to think about the way you meshed things — not just with Tony Williams’ legacy, but with the musicians in the band. How difficult was it at first, with such established voices in the room?

VERNON REID: It started out as a conversation with Jack Bruce, in the back of a tour bus. And then it took a really long time to get the schedules together. Everyone played really well, from the first. But it wasn’t until we played a second run of shows on another tour, when we played in California, we played in New York and we played in Seattle. That’s when, in that next run of shows, some other thing clicked in with the four of us. We entered in from another place. It was much more intimate. It had been tight before, but there was something else going on. At the end, after the Seattle show, that’s when we went right into the studio. It’s like, if you wait with something that, when people are really engaged and connected, you can’t count on that engagement and connection later on.

NICK DERISO: Though you rose to fame with Living Colour, jazz was always a passion. I remember a duo record, early on, with Bill Frisell. Tony Williams was obviously a part of your musical life, as well. How did all of that feed into Spectrum Road?

VERNON REID: I was turned on to Tony Williams in high school by a classmate. He was also a big Jack Bruce fan. As fate would have it, I wound up playing with Jack Bruce for his (1990 solo) record A Question of Time, and stayed connected with him over the years. So, it’s partly the craziness of being a fan, because I had this really rare thing that happened: You really get into someone, and then you connect with them. That was one part of it. The connection to Cindy Blackman was hearing her and just being blown away. There was also the fact that, like Tony, she was a great rock drummer. Tony was completely embraced in jazz, and was considered a wunderkind, but he was an insanely great rock drummer. Cindy is the same way. I had seen her in a jazz context, and then killing it with Lenny Kravitz. So, we both have this same kind of split. That’s something all of us have in common — this rock ‘n’ roll life, but with this jazz component to what we do. I met John Medeski at the very beginning of Medeski Martin and Wood, and listened to him play with the Either Orchestra. He was such a mad scientist, a fascinating musician both in terms of improvisation but also the textural. So, I had this idea that this quirky combination would work, and it eventually became Spectrum Road.

NICK DERISO: Expanding musical boundaries is a passion you share with Tony Williams, too. I remember your first solo album (1996’s Mistaken Identity), recorded with jazz legend Teo Macero and hip-hop producer Prince Paul.

VERNON REID: That record, it’s insane that I got away with it. That record basically has me in between two incredible producers. Teo was such a special person, and such an awesome artist in his own right. I learned so much about producing from being with him. He had a tremendous sense of appropriateness, what things were working and what things were not working. Then there was Prince Paul, who produced De la Soul, and it really, really worked. When I go back to that record, I find that it carves out a unique space — like having Don Byron and DJ Logic in the same room, getting an amazing 16 bars from Chubb Rock. Just the fusion of the hip hop idea, the metal thing, the blues thing — all of that stuff. It came together brilliantly.

NICK DERISO: If you go back to the Miles Davis records, Teo Macero was kind of a prototypical scratch DJ — editing together pieces of songs from these all-day jams to form songs.

VERNON REID: The thing, too, that’s extraordinary is that when you think about Miles, he had this fierce reputation. But the trust he had in Teo Macero to make the records work is unbelievable. To have that level of trust for an artist of that level — for a Miles Davis to say: “OK, you make it,” and not interfere. To never say, “don’t use this part, because this part makes me look bad.” He would go: “Make it happen,” and Teo would take all of these things, and create from what Miles did. Incredible. In the mindset that people have today, where control is everything, for someone to let go and trust another individual like that, it’s extraordinary. It’s not the usual thing.

NICK DERISO: Like a lot of people, I saw you for the very first time when Living Colour opened up for the Stones — and it struck me what a great proponent Mick Jagger was for the band. You guys appeared on Primitive Cool, he appeared on Vivid. It must have made you feel vested, finally. You had the rock-star stamp of approval.

VERNON REID: It’s funny, the Stones said and did things that were extraordinary — like “Brown Sugar.” What American artist would even approach that territory, until Steely Dan came around? There is no American singer who would go near that — nowhere near it. They championed Stevie Wonder, they championed Billy Preston, certainly a lot of black artists. Prince opened for them. There were a lot of very cool things over the years. We were thankful to be a part of that.

NICK DERISO: The new album sent me back to Living Colour’s debut, and I found it’s held up remarkably well — a tribute, really, to the band’s heady mixture of styles. When is the last time you returned to Vivid?

VERNON REID: It’s funny you should bring up Vivid when we’re talking about Spectrum Road. Making this record — though it’s many years later, and it’s very different music — had the same feeling of connection, the same sense of doing something where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. That was a very intact kind of feeling. You know, we just had a big anniversary for Vivid, a 24th anniversary. That record is such a moment in time. I remember feeling that working with the band, and working with (producer) Ed Stasium, was very much a peak experience — and that was before the record took off. It really was one of the great moments, because it was the culmination of something that seemed impossible. The fact that we were making the record, period, was amazing. We went from playing in empty rooms, to filling our favorite club CBGBs, to the most famous rock star in the world coming to see us — Mick Jagger. He said, “Man, you guys are really cool. How would you feel about recording a demo?” All of those steps, leading up to the making of the record, it was a fantastic time. With debut records, if you can get out of the way of the music, it can be a magical experience. It happened on Vivid, and it certainly happened with the Spectrum Road record.

NICK DERISO: I wondered what you thought the fruits of your efforts have been with the Black Rock Coalition. Is it easier today, in your opinion, than it was 25 years ago for an aspiring African American musician to break out of that static role of either R&B croon or rapper?

VERNON REID: I think the needle has moved, but not nearly as much as it needs to. When I think of the tapestry and the culture that we helped to create, I’m proud. Rage Against the Machine happened after us, TV on the Radio. That would have been unimaginable 25 years ago. They make hugely different music, but I’m proud that in some way — maybe in an infinitesimal way — we were part of the way certain things unfolded. Similarly, we wouldn’t exist without the Bad Brains. We wouldn’t exist without a lot of other bands that are completely forgotten. This is just the way it is. Now, there’s a sense of community that’s extended, say, into Afropunk. They are doing what they do in a very different way, but it’s great to see the way it’s expanded. One of my favorite bands right now is the psychedelic group Earl Greyhound. They’re very much their own thing, very unique. We’re proud to be part of the thing that would allow something like that to happen.

NICK DERISO: There was a visual element to the revolution, maybe in direct contrast to the old saying about whether or not it would be televised. I think that seeing bands like yours on MTV, in parallel to seeing Cosby in prime time, might have initially been only drops in the bucket — but eventually all of it became a tidal wave of change on the race issue.

VERNON REID: I would say that society changes slowly over time. Like stopping smoking, you want to stop smoking but you are caught up in it. Eventually, you turn around and you haven’t smoked for two years, and you’re OK. That’s sort of the way it is. I remember when saying things like “President Obama” was like putting yourself in the middle of a science-fiction novel. But, ultimately, we’re going to have a female president. We’re going to have a Latino president, an Asian president, a Jewish president. We’re going to have a Native American president. It may take another 50 years, but I guarantee you, it’s going to happen.

- How Deep Cuts on ‘Music From Big Pink’ Underscore the Band’s Triumph - July 31, 2023

- How ‘Islands’ Signaled the Sad End of the Band’s Five-Man Edition - March 15, 2022

- The Band’s ‘Christmas Must Be Tonight’ Remains an Unjustly Overlooked Holiday Classic - December 25, 2016