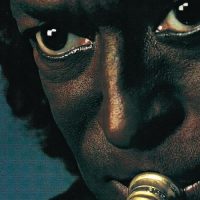

The successful jazz-rock experiments Miles Davis oversaw in 1969 with the one-two punch of In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew were plenty enough to forever put his mark on the genre and was even good enough for his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. But the restless jazz legend felt he was just getting warmed up and by the end of the year declared “I could put together the greatest rock ‘n roll band you ever heard.” When he walked into Columbia’s New York studio with his supporting musicians on April 7, 1970 to record the basic tracks for the album that became A Tribute to Jack Johnson, he made a strong case for backing up that statement.

For the first time since 1957’s Ascenseur Pour L’échafaud, Miles was tasked with coming up with a soundtrack for a motion picture. A documentary of an early 20th century heavyweight boxer, Miles felt a strong connection with the subject, who paid for the success he enjoyed and flaunted because he was black. Davis related to Johnson’s aggressive nature, a burning desire to be the best in his profession and living life to the fullest.

Given an assignment he can really sink his teeth into, you would think Miles approached this project with more preparation and planning than his famously extemporaneous sessions for Kind Of Blue and the two fusion classics of the prior year. Instead, we get a mess of wrong notes, broken down instruments, awkward edits and riffs invented on the spot. But man, what a beautiful mess it was.

On that spring day in New York City, Miles Davis calls in soprano saxophonist Steve Grossman, drummer Billy Cobham, bassist Michael Henderson and guitarist John McLaughlin. Only Johnny Mac had previously recorded with the leader and Grossman was barely out of high school and replaced the great Wayne Shorter in the sax chair just a couple of weeks earlier. Henderson was also just hired and possessed no background in jazz. Billy Cobham already came with jazz and jazz-rock credentials having played for Horace Silver and the early fusion ensemble Dreams. But even he had no idea about what was going to transpire that day.

While the band is waiting for Miles to wrap up a conversation with producer Teo Macero in another room, John McLaughlin picks up his guitar and starts playing a simple “boogie in E” as he calls it. Henderson and Cobham quickly pick up on it and soon the ensemble is up and going without its leader and the tape rolling. Shortly after two minutes have gone by in which McLaughlin is playing somewhere between a lead and rhythm guitar Miles walks into the studio and picks up his horn. To herald the leader’s impending entrance into the song, McLaughlin shifts over to a B-flat chord and Miles Davis commences with almost eight minutes of some of the most maximal trumpet playing of his career.

Like his role model for the project, Davis is aggressive, even boxer like, dancing around, make some well placed jabs/notes at times and unleashing a flurry of hits during others. After Michael Henderson is embarrassingly slow to pick up the chord change, Miles coaxes him by playing a note on his trumpet that fits both the E and B flat. Henderson rights the ship and continues to play the solid looping, circular style that he was brought on to provide. Meanwhile, Cobham keeps the hard, train-like rhythm going strong punctuated by some killer fills all over the place.

Later on during this jam, after Davis and Grossman solos, Herbie Hancock happened to be literally walking by the room holding a sack of groceries when Miles motions him in and points him to an old Farfisa organ that wasn’t even plugged in(!). An engineer turns it on during recording and Hancock desperately tries to coax sound out of it, to the point of laying his arm across the keys. More soloing by Miles Davis follows and McLaughlin with a more cutting solo than his earlier semi-comping that both recalls and rivals Jimi Hendrix. Finally, the tune fades out just shy of twenty-seven minutes long. The final product, a vinyl side-long track later labeled “Right Off”, includes a couple of ambient interludes that Teo Macero later inserted presumably to break up the extended piece, but they also disturb the flow of the song. After hundreds of listens I’m still on the fence as to whether this was a good thing or not, but it certainly adds to the fascination.

Side two of A Tribute to Jack Johnson opens with another track lasting nearly half an hour, titled “Yester-Now.” Recorded probably the same day and using the same personnel as “Right Off,” it’s a more structured, slower moving piece. The first section is the central melody from James Brown’s “(Say It Loud) I’m Black And I’m Proud”, but slowed way down. Gradually, the tension increases but just as it reaches mid-tempo at the twelve and a half minute mark, another Macero edit appears, this time taking an excerpt from “Shh/Peaceful” from In a Silent Way. Following this interlude is about ten minutes from a track recorded a couple of months earlier, eventually named “Willie Nelson.”

This also features John McLaughlin, but the rest of the personnel instead includes Chick Corea (keys), Jack DeJohnette (drums), Bennie Maupin (bass clarinet) and Dave Holland (bass) – and the only appearance on a Miles Davis record by whack jazz guitarist Sonny Sharrock. A more tense tempo than the first section, the interplay among McLaughlin, Davis and Corea is what makes this portion really stand out as the two guitarists along with Corea provide way-out effects that date the sound, but also keeps the listening engaged. Eventually, Teo Macero crossfades the Willie Nelson section into an ominous sounding orchestral coda lifted from the piece “The Man Nobody Saw” with Miles’ beautiful tone dubbed on top of it. Finally, a few spoken words from Jack Johnson, as recited from actor Brock Peters ends the entire record.

Of all of Miles Davis records, this one is perhaps the most intriguing. It’s less than perfect in many respects, but the imperfections are such that they only add to that intrigue and thus, actually enhance the record. Miles came into the studio with no real plan but a goal. And once again, his vision, creativity, leadership, and musicianship made his lofty goal…to deliver a damned good ha

rd rocking fusion album…a reality.

Note – a tip of the hat goes to Paul Tingen, whose Miles Davis biography “Miles Beyond” provided much of the fascinating story behind these recording sessions.

- Claudio Scolari Project – ‘Opera 8’ (2024) - April 25, 2024

- Nick Millevoi – ‘Moon Pulses’ (2024) - April 23, 2024

- Cannonball Adderley – ‘Poppin’ in Paris: Live at L’Olympia 1972′ (2024) - April 20, 2024